(ITUNES OR Listen Here)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

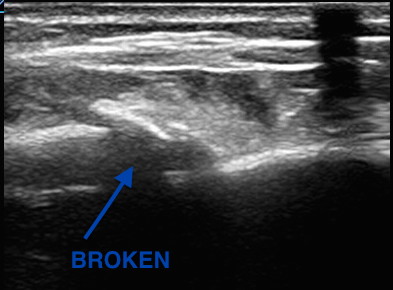

This week we cover a joint piece between the Ultrasound Podcast and SonoIn5 on diagnosis of rib and sternal fractures with ultrasound.

Technique: Linear probe, in line with the long axis of the bone (vertical for sternum, horizontal-ish for ribs).

Diagnosis: Cortical disruption (step off). Excellent sensitivity for sternal fractures [1-3]

- Caution with sternal fractures as the sternomanubrial joint can mimic fracture, but looks more “bumpy” (see below)

Core Content – Rib and Sternal Fractures

Tintinalli (7e) Chapters 258, 259; Rosen (8e) Chapter 45

Rib Fractures

Diagnosis:

- Chest x-ray initial test of choice – may miss 50% of fractures, unclear if this is clinically significant [6]

- Ultrasound has found to have excellent sensitivity [7]

- Rib films are NOT recommended [4-6].

Complications: Traumatic rib fractures may be associated with other traumatic injuries such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, or in the case of lower rib fractures, intra-abdominal injury. However, rib fractures themselves have been associated with mortality, most often as sequelae of pulmonary embarrassment including pneumonia, intubation, and death. Mortality in elderly patients with rib fractures is significantly higher than the younger counterparts at 22% and 10% respectively [8,9].

- Mortality is between 3-13%

- Risk stratification (see this post): Battle and colleagues developed a prognostic scoring system, not externally validated and unclear if it would change practice, that highlights common sense predictors of poorer outcomes:

- Age (>65)

- Higher number of rib fractures

- Chronic lung disease

- Hypoxia (<90%)

- Pre-injury anticoagulant use [11]

Treatment

- Analgesia:

- Often includes NSAIDS (ibuprofen), acetaminophen, and narcotics +/- gabapentin (ibuprofen and gabapentin depending on renal function)

- Epidural analgesia – highly recommended in the EAST guidelines [14].

- Paracostal analgesia (ex: ON-Q pump) – not sufficient evidence for EAST recommendation (2005) [14]

- Pulmonary Hygiene (formerly pulmonary toilet): involved incentive spirometry, coughing, mobilization (up, out of bed), and possibly chest physical therapy

- ORIF, “rib fixation” or “rib plating,” is increasingly common in the US and studies have found improvements in ICU LOS and ventilator days [15]

Disposition

- Many rib fracture patients will need to be admitted to the hospital for pain control, observation, and pulmonary hygiene.

- Some rib fracture patients may benefit from care at trauma centers. Lee et al wrote that 3+ rib fractures exists as an indication for transfer to a level 1 trauma center and many places ascribe to this, it depends on the hospital and physicians.

- While patients in the ED may look good, patients may benefit from high intensity floors (ie stepdown units) and many patients get observed in ICUs, again, depending on local practice patterns. Some protocols risk stratify patients (i.e. to the ICU vs floor) by incentive spirometry.

- Patients with adequate pain control who are low risk (younger, <3 rib fractures, good effort on incentive spirometry) may be discharged from the ED with analgesia and education on importance of pulmonary hygiene

Sternal Fractures – more common with ubiquity of airbags and seatbelts.

Diagnosis: Classically the “gold standard” has been lateral x-ray. However, CT technology has improved since those studies. Ample literature suggests that ultrasound has excellent sensitivity [1-3].

Complications: Historically, sternal fractures were associated with injuries of the great vessels, high mortality, and blunt cardiac injury (BCI) [16-18]. The most recent iteration of the EAST guidelines states, “the presence of a sternal fracture alone does not predict the presence of BCI and thus should not prompt monitoring in the setting of normal ECG result and troponin I level” (Level 2) [18].

Treatment: Analgesia. Most patients with isolated sternal fractures (no pneumothorax, hemothorax, BCI, or hemodynamic instability) that have adequate pain control can be discharged from the ED [1-2].

Blunt Cardiac Injury

A broad category including a range of injuries from clinically silent dysrhythmias to cardiac wall rupture or vasospasm. BCI often results from high impact injury and should be considered in patients with significant thoracic trauma including rib fractures, sternal fracture, pneumothorax, hemothorax, and pulmonary contusion.

Diagnosis: There is no gold standard test. One can rule out BCI with a normal ECG and a single normal troponin I [18].

Management: If an ECG or troponin is abnormal, admit to telemetry for monitoring and echo.

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. A 23-year-old man presents with chest pain after a motor vehicle collision. The patient’s chest struck the steering wheel. He has no other complaints or injuries. Chest X-ray is unremarkable. ECG shows sinus tachycardia with anterior ST depressions. A troponin is sent and is positive at 3.50 mg/dl. [polldaddy poll=9134639]

Question 2. A 20-year-old man presents with left rib pain after falling while playing soccer and striking his chest. Vital signs are normal. On physical examination, the patient has tenderness to palpation over the 4th rib in the midaxillary line. [polldaddy poll=9134640]

Question 3. A 32-year-old woman was the restrained driver involved in a head-on motor vehicle collision (MVC) 2 days prior to presentation. She is complaining of chest pain and bruising to her chest. Her blood pressure is 118/78 mm Hg, pulse is 88 beats/minute, respirations are 18 breaths/minute and oxygen saturation is 96% on room air. You note bony tenderness and ecchymosis to her sternum. You order a chest X-ray and diagnose a non-displaced sternal fracture. [polldaddy poll=9134643]

Answers

- This patient presents with a myocardial contusion and should have an echocardiogram performed to look for any cardiac damage. Myocardial contusion describes a nebulous condition. It can occur through several mechanisms including a direct blow to the chest and compressive force over a prolonged period of time. Histologically, the disorder has similar findings to those seen after acute myocardial infarction. The majority of contusions heal spontaneously but small pericardial effusions may develop. Delayed rupture after resorption of hematoma is feared but rare complication. Patients with myocardial contusion will present after trauma with external signs of trauma and typically have other concomitant thoracic lesions (pulmonary contusion, pneumothorax, hemothorax). Patients will typically have tachycardia (up to 70%). ECG may show dysrrhythmia or ST changes but may also be normal. Although it is not effective to admit all patients for workup for myocardial contusion and the disease has a very low rate of cardiac complications, in the presence of ECG changes and elevated biomarkers, observation and echocardiography are a reasonable approach. Echocardiogram can be used to diagnose pericardial effusion, thrombi formation and valvular disruption.Cardiac catheterization (A) is not necessary after a myocardial contusion as coronary artery obstruction is not part of the pathophsyiology. The patient should not be discharged home (B)without an echocardiogram. Pericardiocentesis (D) is only necessary in the presence of a large pericardial effusion or one causing cardiac tamponade.

- This patient presents with signs and symptoms consistent with a rib facture. A chest X-ray should be performed to rule out any other pathology including pneumothorax and pulmonary contusion. Rib fractures are a common injury after thoracic trauma and the incidence increases with increasing age. They may be associated with a number of potential complications including pulmonary contusions, hemothorax, penumothorax and post-traumatic pneumonia. Fractures are most common at the posterior angle, which represents the weakest area. The ribs most commonly fractured are the 4th – 9th ribs. The 9th – 11th ribs are mobile, which reduces the risk of fracture. However, fractures of these ribs are more likely to be associated with intraabdominal injuries. Rib fractures should be suspected based on history and clinical evaluation. Patients will present with chest pain and tenderness over the area. Imaging should be obtained to rule out the more serious associated complications of pneumothorax, hemothorax and pulmonary contusion. Chest X-ray is the appropriate modality for this but often will not demonstrate the presence of a single rib fracture when it is in fact present. This is particularly true of non-displaced fractures. Rib belts (B) are discouraged as they may decrease the depth of respiration and lead to atelectasis and pneumonia. CT scan of the chest (D) is not routinely required for management of a simple rib fracture. Analgesia and discharge home (A) is likley to occur once more serious pathology is ruled out with a chest X-ray. Patients with rib fractures should also receive an incentive spirometer to help reduce the complication of pneumonia.

- Isolated, non-displaced sternal fractures are associated with low overall mortality rates. Fractures and dislocations of the sternum are caused primarily by anterior blunt chest wall trauma during a head-on MVC. Isolated fractures of the sternum most commonly occur when the chest wall is thrust against a diagonal seatbelt strap during rapid deceleration in a frontal impact MVC. They are more common in older individuals and women. Most fractures are transverse and non-displaced and can be diagnosed on a lateral chest radiograph. Although a fracture of the sternum can be seen following major thoracic trauma, its presence alone does not indicate severe underlying thoracic injury. However, if other significant underlying thoracic injuries are suspected, a CT-scan of the thorax should be performed

References:

- You JS, Chung YE, Kim D, Park S, Chung SP. Role of sonography in the emergency room to diagnose sternal fractures. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 38(3):135-7. 2010. [pubmed]

- Engin G, Yekeler E, Güloğlu R, Acunaş B, Acunaş G. US versus conventional radiography in the diagnosis of sternal fractures. Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden : 1987). 41(3):296-9. 2000. [pubmed]

- Jin W, Yang DM, Kim HC, Ryu KN. Diagnostic values of sonography for assessment of sternal fractures compared with conventional radiography and bone scans. J Ultrasound Med. 2006 Oct. 25(10):1263-8; quiz 1269-70.

- ”Pulmonary Trauma” Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. Ch 258.

- “Thoracic Trauma” Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. 8th ed. Chapter 45.

- Henry TS, Kirsch J. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® rib fractures. Journal of thoracic imaging. 29(6):364-6. 2014. [pubmed]

- Chan SS. Emergency bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of rib fractures. The American journal of emergency medicine. 27(5):617-20. 2009. [pubmed]

- Ziegler DW, Agarwal NN. The morbidity and mortality of rib fractures. J. Trauma. 1994;37(6):975–9.

- Bulger EM, Arneson M a, Mock CN, Jurkovich GJ. Rib fractures in the elderly. J. Trauma. 2000;48(6):1040–6

- Flagel BT, Luchette F a, Reed RL, et al. Half-a-dozen ribs: the breakpoint for mortality. Surgery. 2005;138(4):717–23; discussion 723–5.

- Battle CE, Hutchings H, Evans P. Risk factors that predict mortality in patients with blunt chest wall trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2012;43(1):8–17.

- Livingston DH, Shogan B, John P, Lavery RF. CT diagnosis of Rib fractures and the prediction of acute respiratory failure. The Journal of trauma. 64(4):905-11. 2008. [pubmed]

- Battle CE, Hutchings H, Lovett S. Predicting outcomes after blunt chest wall trauma: development and external validation of a new prognostic model Critical Care 2014, 18:R98

- Pain Management in Blunt Thoracic Trauma (BTT). J Trauma. 59(5):1256-1267, November 2005.

- Doben AR, Eriksson EA, Denlinger CE. Surgical rib fixation for flail chest deformity improves liberation from mechanical ventilation. Journal of critical care. 29(1):139-43. 2014. [pubmed]

- Screening for Blunt Cardiac Injury. J Trauma. 73(5):S301-S306, November 2012

- Karangelis D, Koufakis T, Spiliopoulos K, Tsilimingas N, Bouliaris K, Desimonas N. Management of isolated sternal fractures using a practical algorithm. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 7(3):170-. 2014. [article]

- Dua A, McMaster J, Desai PJ et al. The Association between Blunt Cardiac Injury and Isolated Sternal Fracture. Cardiology Research and Practice. 2014:1-3. 2014. [article]