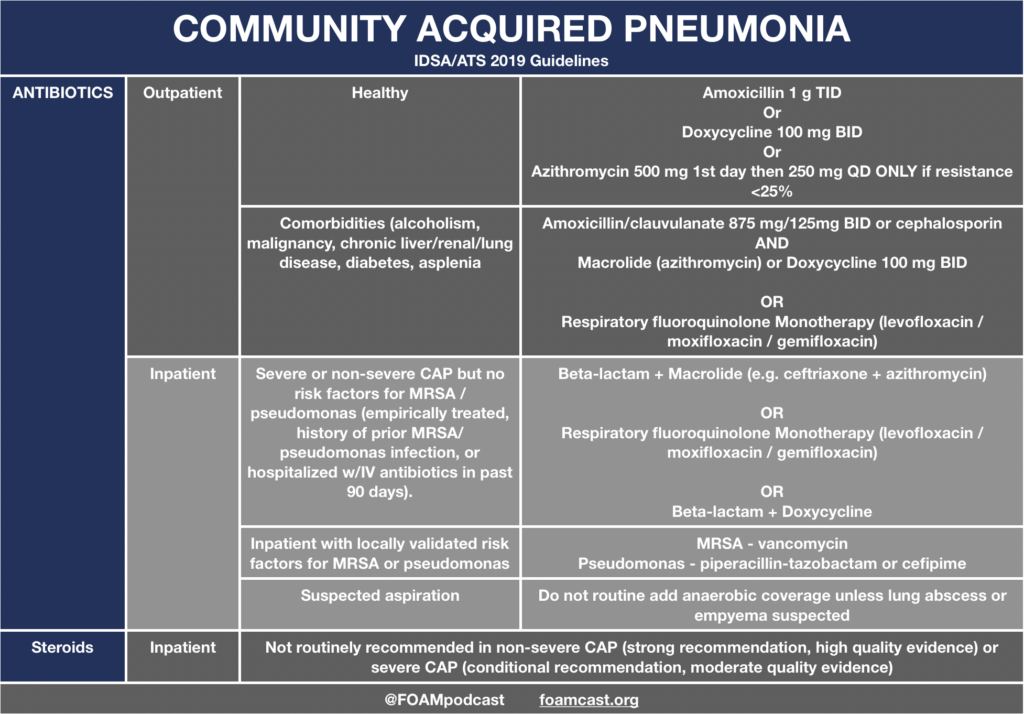

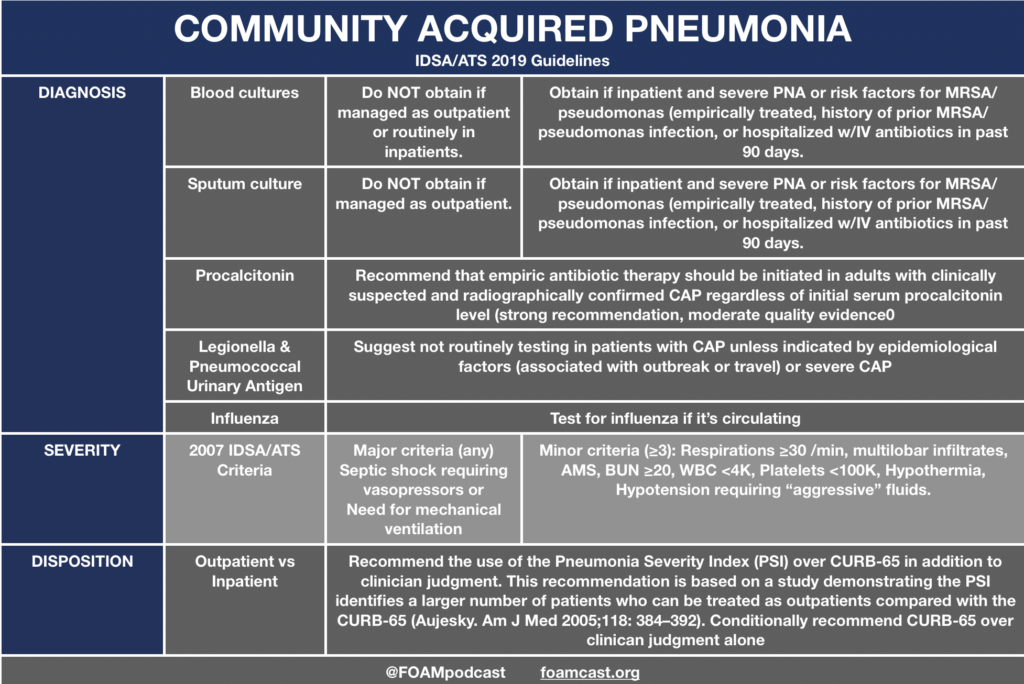

In this episode, we reivew the evaluation and management of community acquired pneumonia (CAP), including the 2019 guidelines from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) / American Thoracic Society (ATS) [1].

Regarding Biomarker Recommendation

Regarding the recommendation against using procalcitonin (PCT) to guide decision making to initiate antibiotics in CAP, the guidelines reference an older Cochrane review. The newer review (2017) claims a mortality benefit but combines trials from ICU/ED/primary care that use PCT to both initiate and/or guide antibiotic treatment. Amongst ED trials, the OR was 0.97 (95 CI 0.70,1.36) for 30-day mortality (I2=0%). For all trials combined, the forest plot demonstrates an OR 0.89 (95CI 0.78, 1.01). However, when adjusted this resulted in an aOR 0.83 (95CI 0.70 ,0.99) [2]. A meta-analysis recently published Ebell et al claims of C-reactive protein (CRP), PCT, and leukocytosis, CRP has promising utility in the diagnosis of CAP [3]. However, no single threshold had adequate operating characteristics (for any of the biomarkers), as the sensitivity/specificity trade-off was quite large. The ACEP draft clinical policy for CAP recommends against the use of biomarkers (Level C recommendation)

Regarding Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) Recommendation

The IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend use of PSI or CURB-65 to identify patients who should be admitted or treated as outpatients. A draft of the American College of Emergency Physicians CAP clincial policy (not yet finalized) did not come to this same recommendation and had a more tempered recommendation – “Use the PSI or CURB-65 CAP mortality decision tools to help identify low-risk patients who may be appropriate for outpatient treatment.” The PSI is long and cumbersome. While it may identify a larger number of patients that can be treated as outpatient, we believe that not all of these test are necessary if you believe a patient can be treated as an outpatient.

References:

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67.

- Schuetz P, Wirz Y, Sager R, et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10:CD007498.

- Ebell MH, Bentivegna M, Cai X, Hulme C, Kearney M. Accuracy of Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Adult Community-acquired Pneumonia: A Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2020; In Press