iTunes or Listen Here

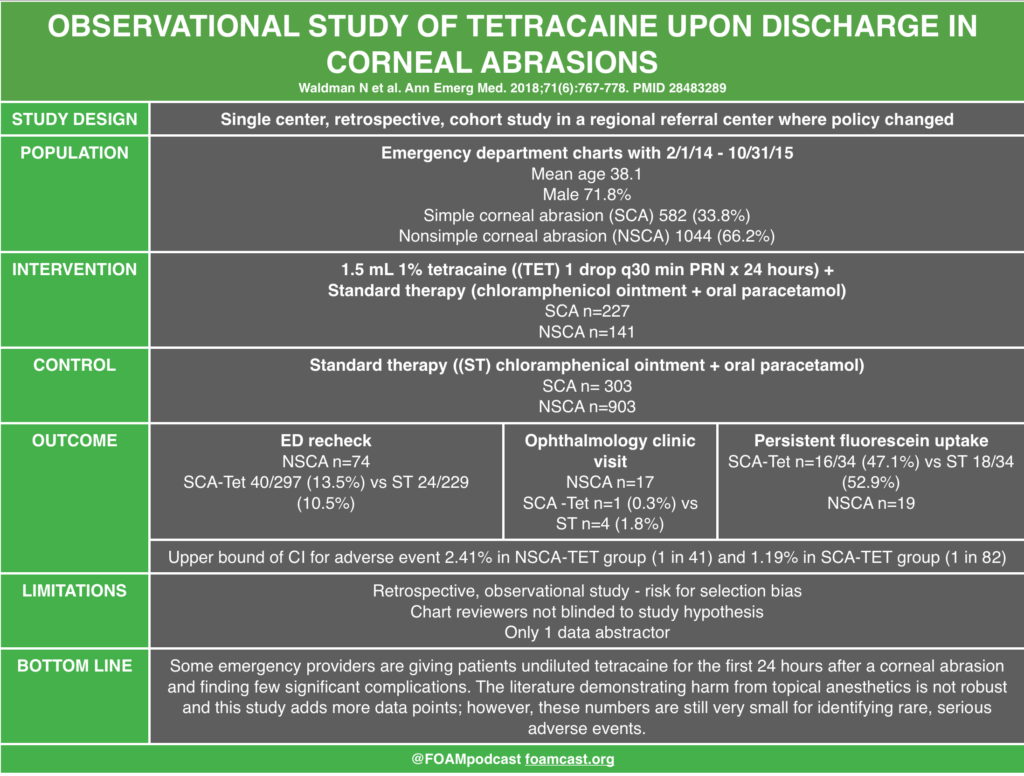

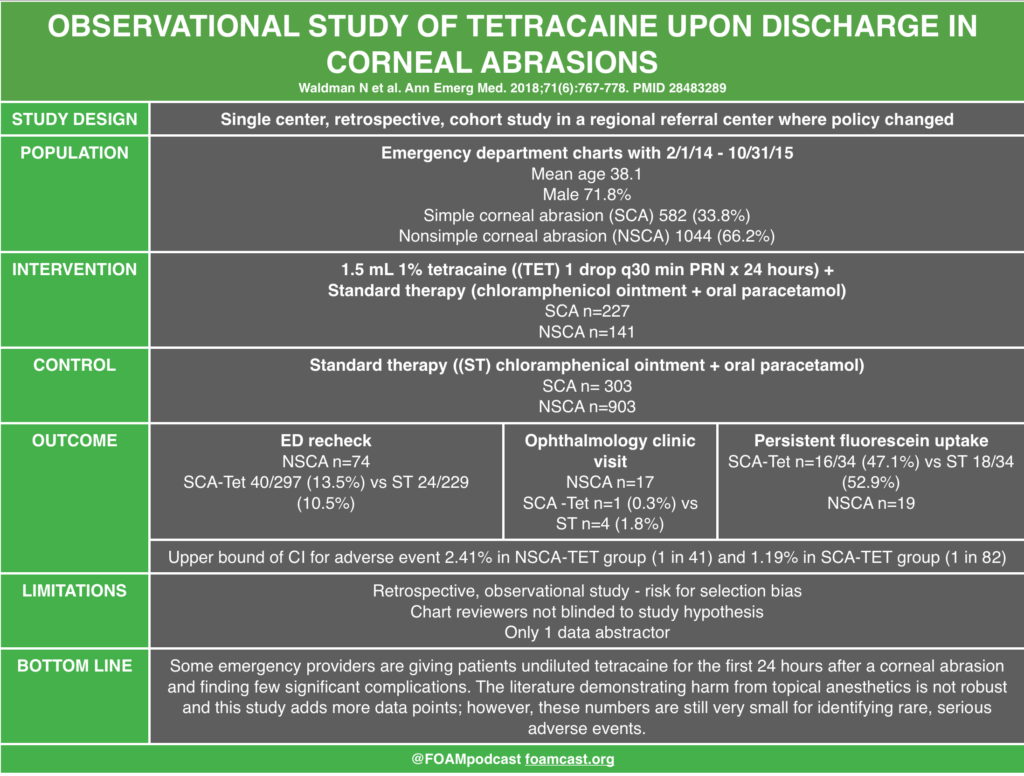

We review one of the editors top picks from Annals of Emergency Medicine, which are free for 6 months from issue release. The article covered in this podcast is Waldman et al, is a study of tetracaine in corneal abrasions.

Review from First10EM on topical anesthetics and corneal abrasions.

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 21-year-old man presents to the emergency department complaining of left eye pain. Fluorescein staining reveals a dendritic lesion over the cornea. What is the most likely diagnosis based on this finding?

A. Bacterial conjunctivitis

B. Corneal abrasion

C. Herpes keratitis

D. Retinal detachment

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

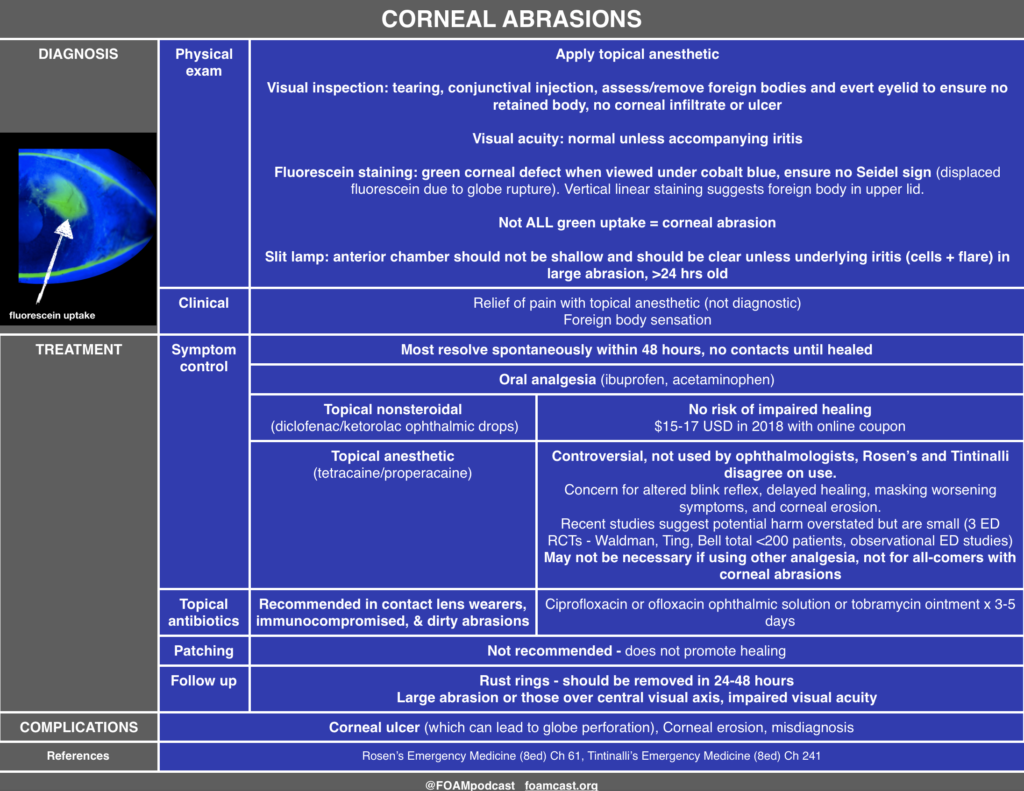

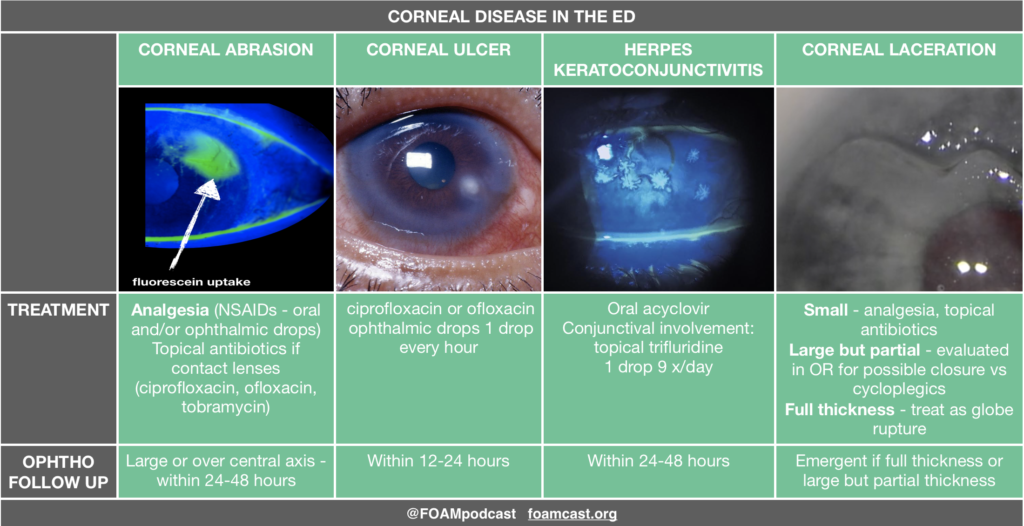

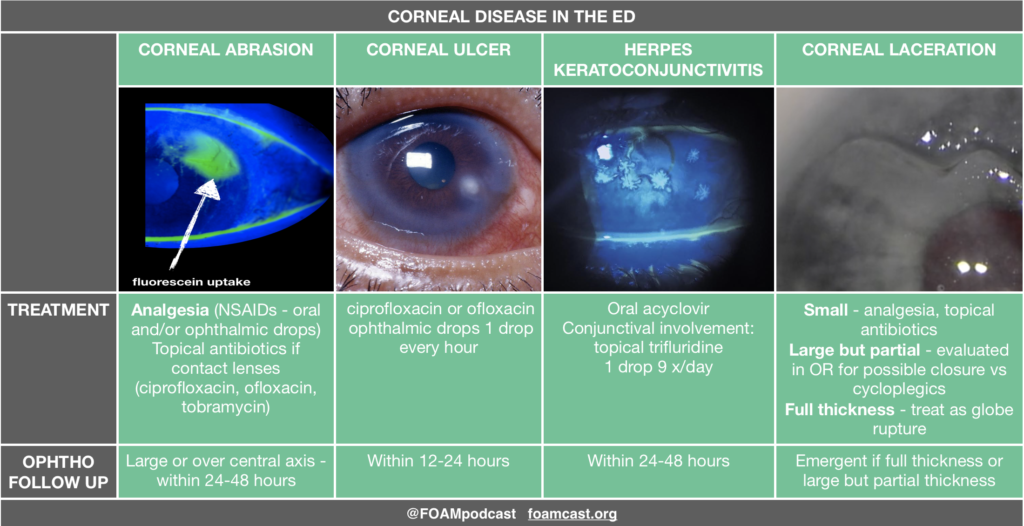

A dendritic lesion of the cornea detected by fluorescein staining indicates the presence of herpetic keratitis. Herpetic keratitis is caused by herpes simplex virus and can lead to blindness because of scarring and opacification of the cornea. A typical presentation includes a painful eye, blurred vision or excessive tearing. Diagnosis can be made with fluorescein staining which gives the classic dendritic appearance. The presence of a dendritic lesion indicates active replication of the virus. Superficial epithelial herpetic keratitis can be successfully treated in two to three weeks with topical antivirals such as ganciclovir. Topical steroids must be avoided in patients with herpetic keratitis as the herpetic lesions can become much deeper and threaten the patient’s vision. Oral antivirals have not been studied comparatively with topical antivirals. Risk of transmission of ocular herpes simplex virus to another person is thought to be extremely low.

Bacterial conjunctivitis (A) can cause eye discomfort but typically presents with copious purulent discharge from one or both eyes. Fluorescein staining of the eye will be negative for any defect. Corneal abrasions (B) present with a superficial epithelial lesion that is usually linear in shape. The cornea is expected to be clear. Retinal detachment (D) is painless and does not cause a change in the appearance of the surface of the eye. Fundoscopic exam will often show rugae indicating the edge of the retina floating in the vitreous humor.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

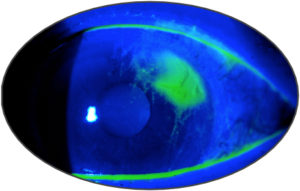

A 20-year-old woman presents to the emergency department for left eye pain. Yesterday she scratched her eye while putting in her contact lens. She has had constant left eye pain and tearing since. She has no foreign body sensation. On exam, her visual acuity is at baseline and equal in both eyes. Her fluorescein exam findings are shown below. Which of the following is the most appropriate treatment for this patient’s condition?

A. Erythromycin ophthalmic ointment

B. Gentamicin-prednisolone ophthalmic suspension

C. Tetracaine ophthalmic solution

D. Tobramycin ophthalmic ointment

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

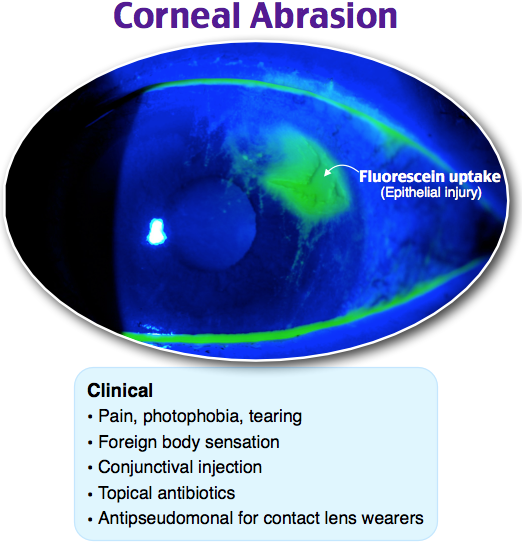

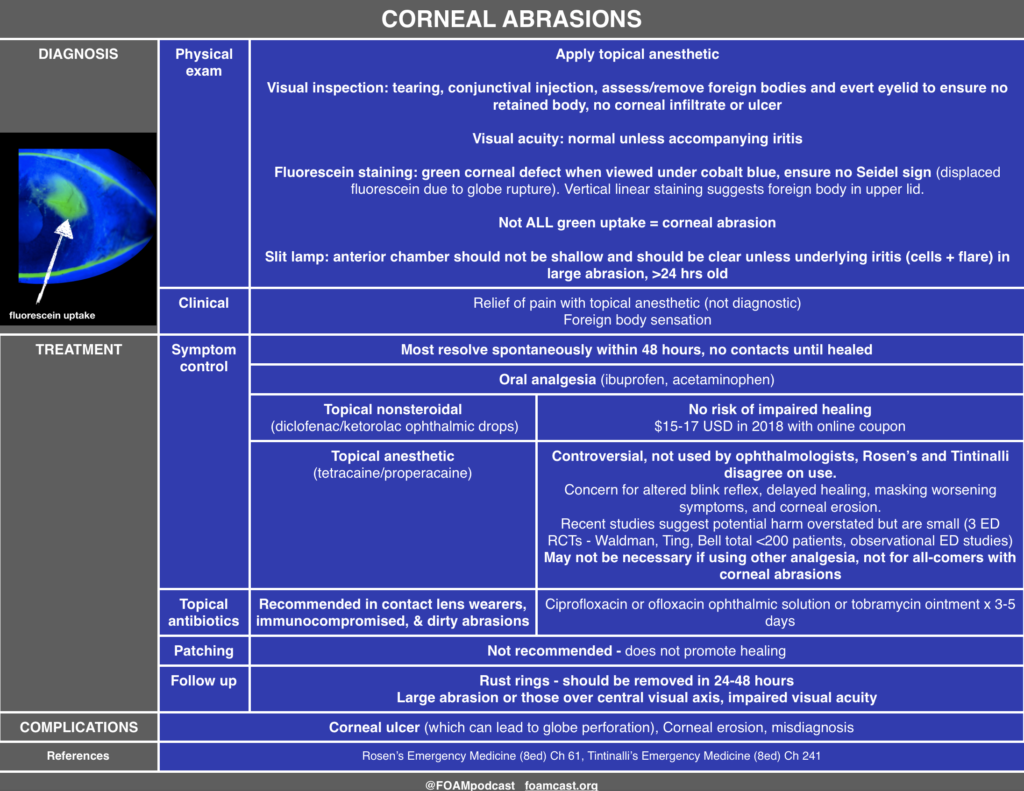

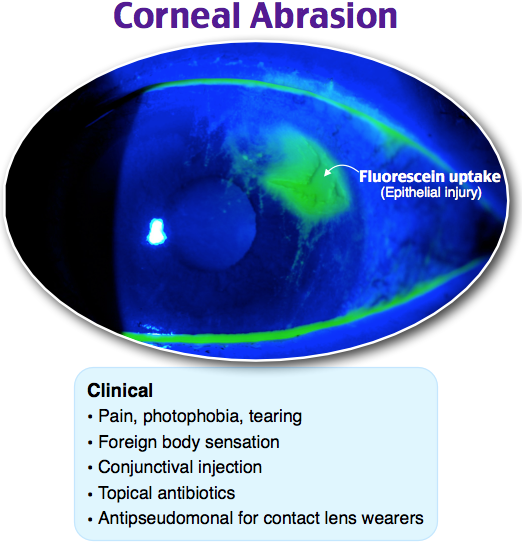

D. This patient’s fluorescein exam is consistent with a corneal abrasion. It is caused by direct mechanical damage, leading to a partial-thickness corneal injury. Athletes, contact lens wearers, welders, and glass workers may present more often with these injuries. Diagnosis is confirmed when fluorescein dye highlights the usually linear or punctate abrasions. Multiple vertical corneal abrasions may indicate a retained foreign body beneath the eyelid. Corneal abrasion fluorescein exam findings are not to be confused with open globe injuries (streaking of the dye from the site of injury), corneal ulcers (circular patches of dye uptake with ragged, “heaped up” edges), and herpes simplex keratitis (dendritic pattern uptake). Patients commonly present with eye pain and tearing with a usually known mechanism of injury. The mainstay of treatment includes pain control, infection prophylaxis, and preventative care to avoid abrasions in the future. Pain control includes cycloplegics like homatropine and cyclopentolate and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Commonly prescribed antibiotic ointments include erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, tobramycin, and gentamicin. Notably, erythromycin does not cover pseudomonal infections, which are more likely to occur in contact lens wearers. Erythromycin (A) does not have appropriate pseudomonal coverage for this patient who wears contact lenses and has a corneal abrasion. Ophthalmic medications containing steroids, like gentamicin-prednisolone (B), should not be prescribed in corneal abrasions or ulcers as they may decrease healing rates. While in the emergency department, tetracaine (C) may be used to more easily evaluate the patient’s eye. However, ocular anesthetics should not be prescribed as they decrease healing rates and block the basic corneal reflex to avoid further injury.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References:

- Waldman N, Winrow B, Densie I, et al. An Observational Study to Determine Whether Routinely Sending Patients Home With a 24-Hour Supply of Topical Tetracaine From the Emergency Department for Simple Corneal Abrasion Pain Is Potentially Safe. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(6):767-778.

- Ball IM, Seabrook J, Desai N, Allen L, Anderson S. Dilute proparacaine for the management of acute corneal injuries in the emergency department. CJEM. 2010;12:(5)389-96.

- Ting JY, Barns KJ, Holmes JL. Management of Ocular Trauma in Emergency (MOTE) Trial: A pilot randomized double-blinded trial comparing topical amethocaine with saline in the outpatient management of corneal trauma. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009;2:(1)10-4.

- Swaminathan A, Otterness K, Milne K, Rezaie S. The safety of topical anesthetics in the treatment of corneal abrasions: A review. J Emerg Med 2015

- Calder LA, Balasubramanian S, Fergusson D. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for corneal abrasions: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(5):467-73.

- Galuma K, Lee J. “Ophthalmology.” Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, Chapter 61, 790-819.e3