iTunes or Listen Here

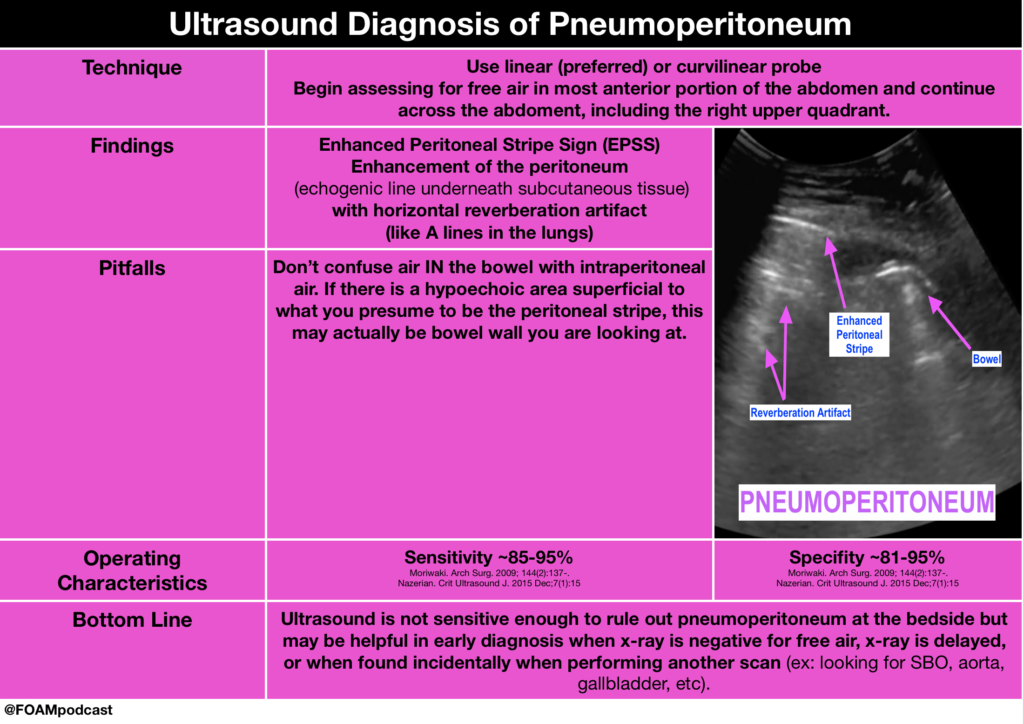

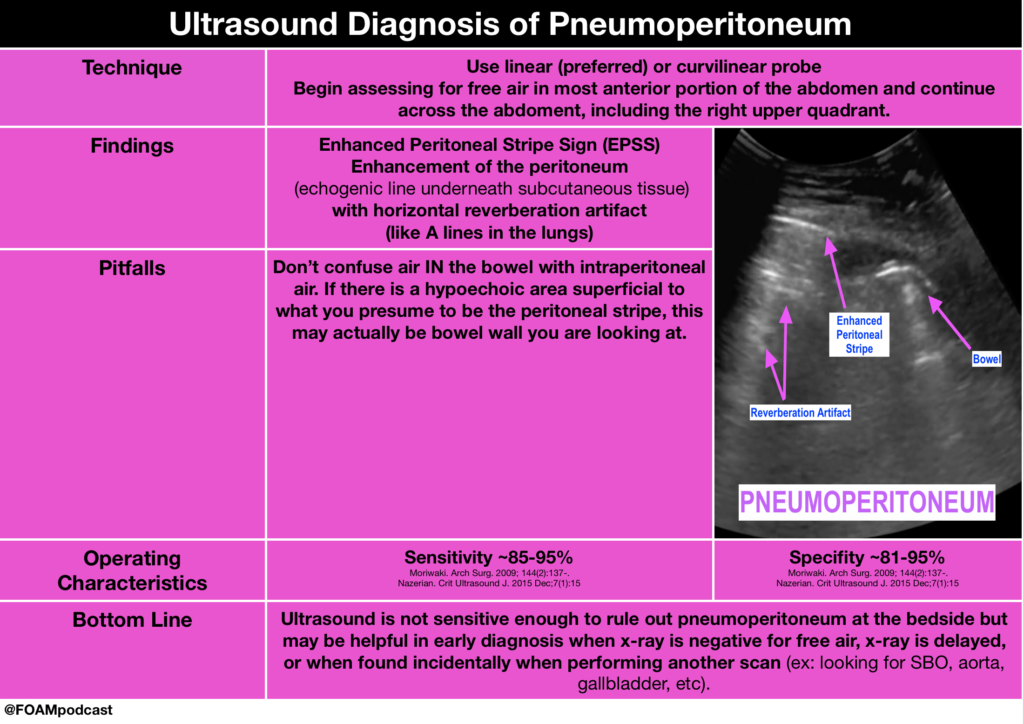

5MinSono has a great 5 minute videocast on the ultrasound diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum.

Core Content

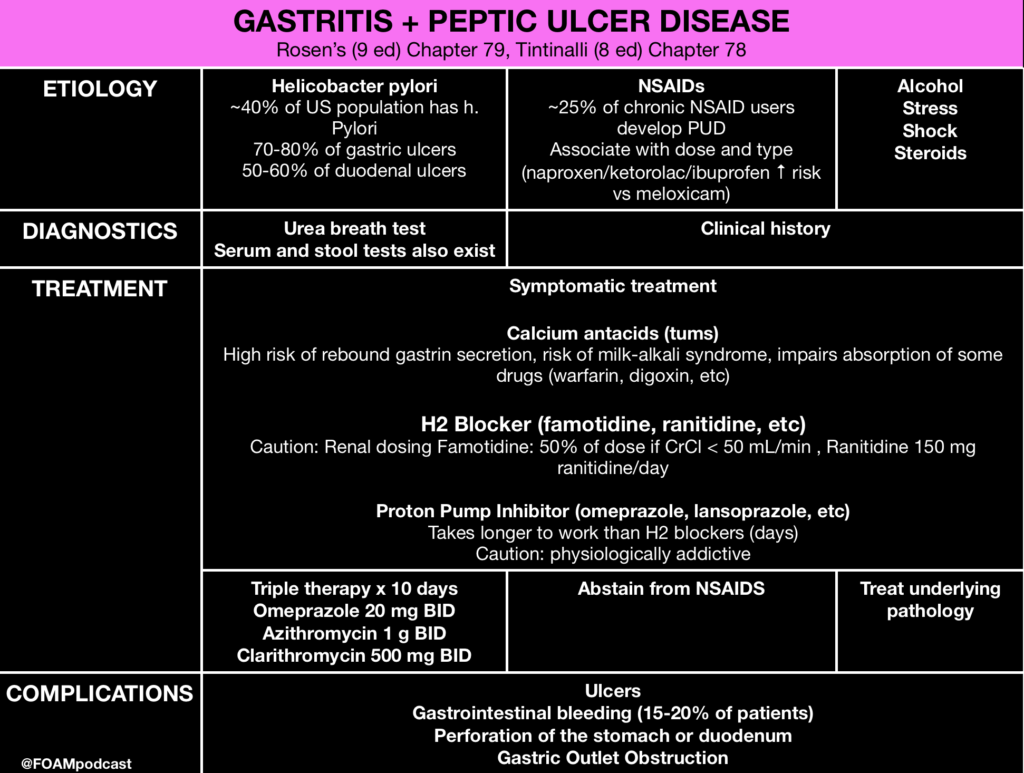

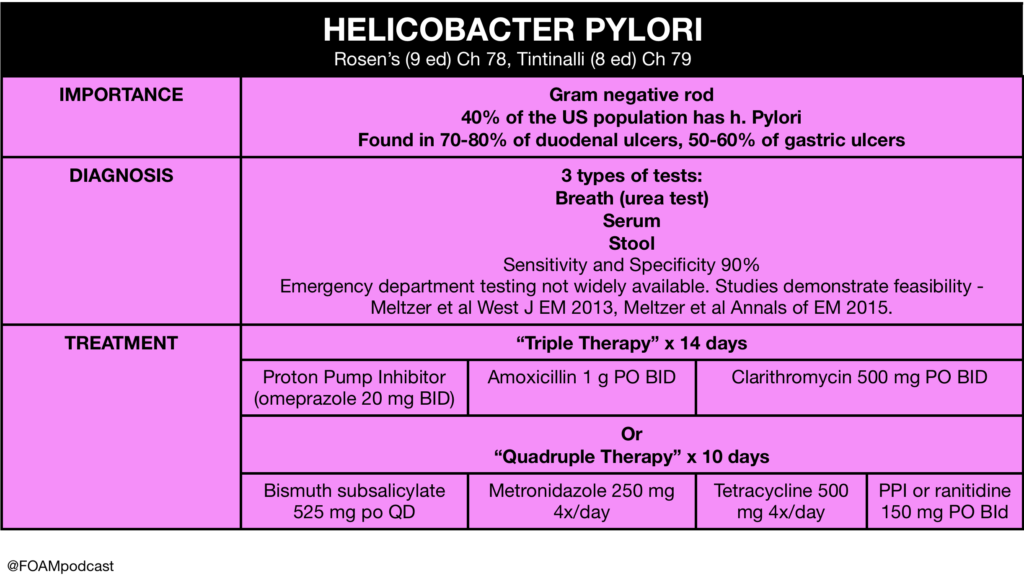

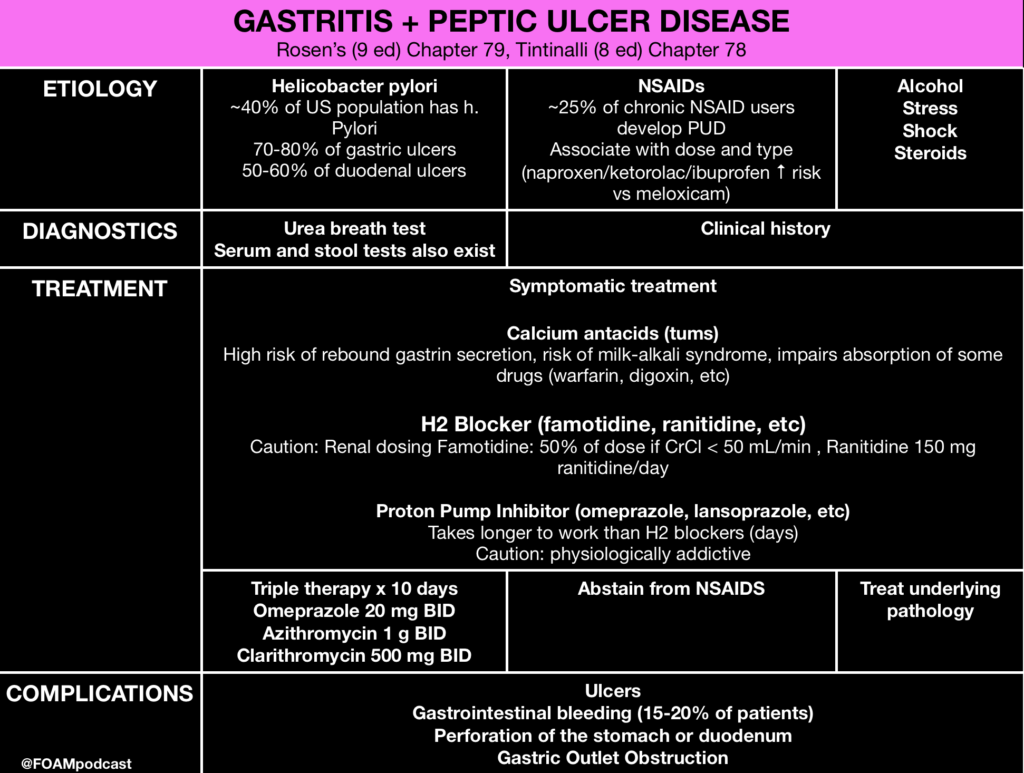

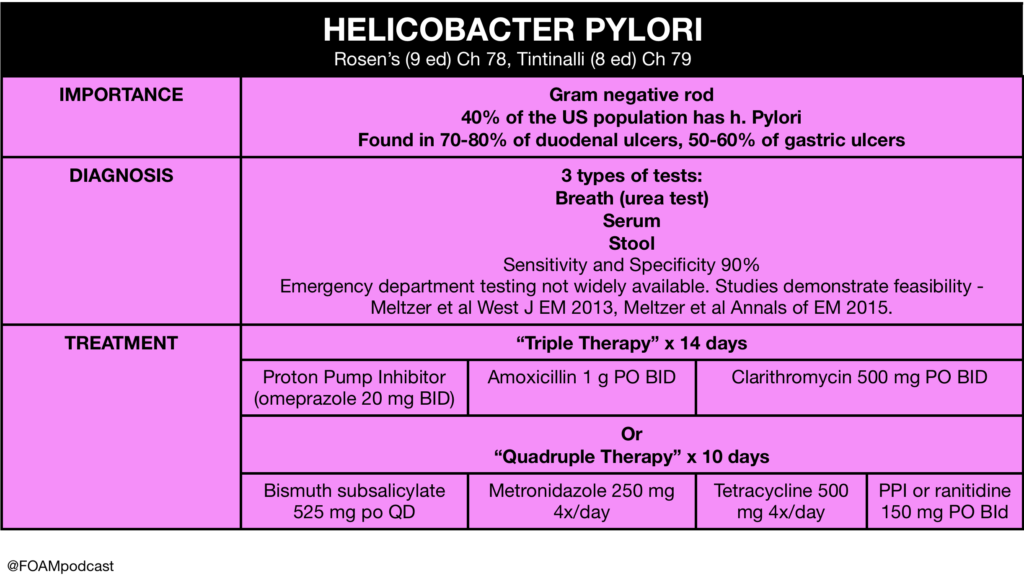

We cover gastropathies and peptic ulcer disease (PUD) using Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (9th ed) Chapter 79 and Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine (8th ed) Chapter 78 as guides.

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 67-year old man with chronic osteoarthritis complains of gnawing and burning in the epigastric area that is occasionally accompanied by nausea and vomiting. His current BMI is 26 and he is physically active. What is the most probable cause for these symptoms?

A. Cholelithiasis

B. Gastric carcinoma

C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced gastritis

D. Peptic ulcer disease

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”] C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) therapy is the first line treatment in osteoarthritis, however chronic NSAID use can often destroy the gastric mucosa leading to hemorrhage, erosions and ulcers. NSAIDs such as naproxen and ibuprofen are the most common agents associated with acute erosive gastritis. A long-term prospective study found that patients with arthritis who were older than 65 years and regularly took low-dose aspirin were at increased risk for dyspepsia severe enough to necessitate the discontinuation of NSAIDs. This suggests that better management of NSAID use should be discussed with older patients in order to reduce NSAID-associated upper GI events. COX -2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib, are an alternate therapy to NSAIDs. Other common agents that cause gastritis include alcohol and Helicobacter pylori. The mainstay treatment of erosive gastritis is to refrain from the offending agent. The gold standard for diagnoses of gastritis is an upper GI endoscopy.

Symptomatic cholelithiasis (A) is often seen in populations who have risk factors for gallstones, which include persons with diabetes mellitus, persons who are obese, women, rapid weight cyclers, and patients on hormone therapy or taking oral contraceptives. This patient does not portray the colicy pain associated with gallstones. Patients with gastric cancer (B) often present with weight loss, dysphagia, postprandial fullness and loss of appetite. Gastric cancer is multifactorial involving both inherited predisposition and environmental factors. Environmental factors implicated in he development of gastric cancer include diet, Helicobacter pylori, previous gastric surgery, pernicious anemia, chronic atrophic gastritis and radiation exposure. Smoking and smoked meats also have a high correlation with gastric cancer. Peptic ulcer disease (D) is a complication of chronic gastritis and can present in a similar manner as gastritis. Peptic ulcers include both gastric and duodenal ulcers. Peptic ulcers present with gnawing or burning sensation that occur after meals. Common risk factors include H. pylori infection and ingestion of NSAIDs. An upper GI endoscopy must be performed to visualize the ulcers. Biopsy is indicated if ulcers are seen on endoscopy in order to rule out Helicobacter pylori. Active ulcers associated with NSAID use are treated with an appropriate course of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy and the cessation of NSAIDs. For patients with a known history of ulcer and in whom NSAID use is unavoidable, the lowest possible dose and duration of NSAID and co-therapy with a PPI is recommended.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

A 55-year-old man presents with severe abdominal pain and tenderness on examination that began acutely approximately 12 hours prior to arrival. His X-ray is shown below. What is the most appropriate next step?

A. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis

B. Nasogastric tube insertion

C. Observation and serial abdominal exams

D. Surgical consultation

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

D. The X-ray demonstrates free air under the diaphragm representing a perforated viscus within the intraabdominal cavity. The presence of free air is an indication for an emergent surgical consultation for repair. The emergency provider should administer broad-spectrum antibiotics covering aerobic and anaerobic organisms along with intravenous fluid resuscitation.

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (A) is indicated if the X-ray does not reveal evidence of free air and the patient has ongoing pain and tenderness requiring a diagnosis. Some perforations will not show on plain films, and as time progresses, the area of perforation may wall off and not show on X-ray. A nasogastric tube (B) is not indicated in the management of a patient with a perforated viscus. Observation and serial abdominal exams (C) are not sufficient for a patient with a perforation.

A patient presents with hematemesis. What test is most likely to determine the etiology of the bleeding?

A. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis

B. Nasogastric tube lavage

C. Right upper quadrant ultrasound

D. Upper endoscopy

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

Upper endoscopy is the modality that is most likely to identify the culprit lesion in a patient with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). UGIB is a common presentation caused by a variety of pathologies including gastritis, esophageal varices, peptic ulcer disease, Mallory-Weiss tears, arteriovenous malformations and Boerhaave’s syndrome. Of these causes, peptic ulcer disease is the most common. Regardless of the etiology, endoscopy represents the best modality for diagnosis. It allows direct visualization of the esophagus, stomach and first two sections of the duodenum. Additionally, it allows for interventions to be performed if active bleeding or stigmata of recent bleeding are found.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (A) is limited in its ability to give a diagnosis. Nasogastric tube lavage (B) may show the presence of blood in the upper GI tract but cannot differentiate between causes. Right upper quadrant ultrasound (C) may give information about the patient including the presence of cirrhosis but cannot give a specific diagnosis as the cause.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References

- Nazerian P, Tozzetti C, Vanni S. Accuracy of abdominal ultrasound for the diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum in patients with acute abdominal pain: a pilot study. Critical ultrasound journal. 7(1):15. 2015. [pubmed]