(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

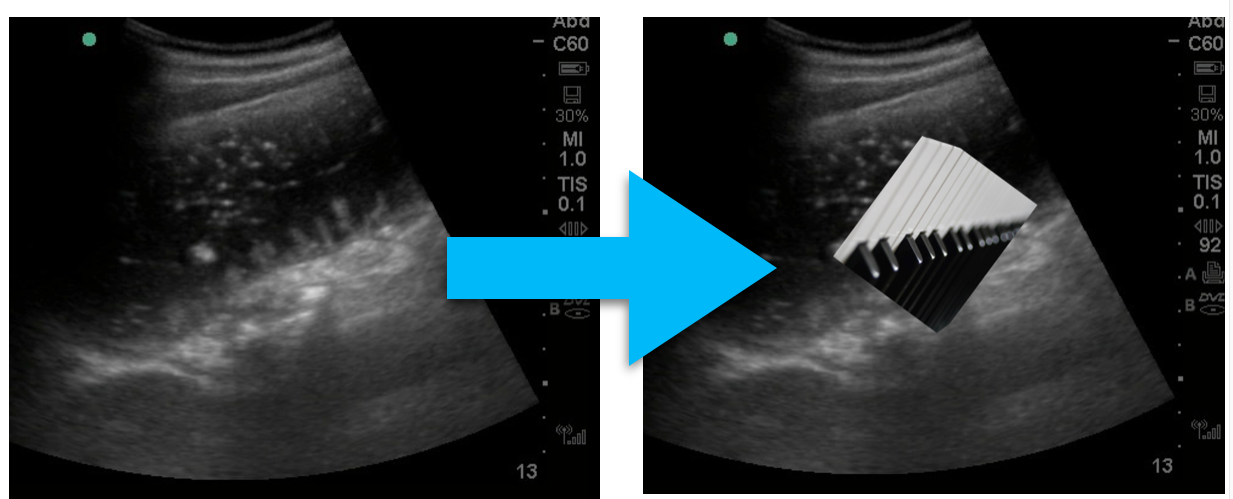

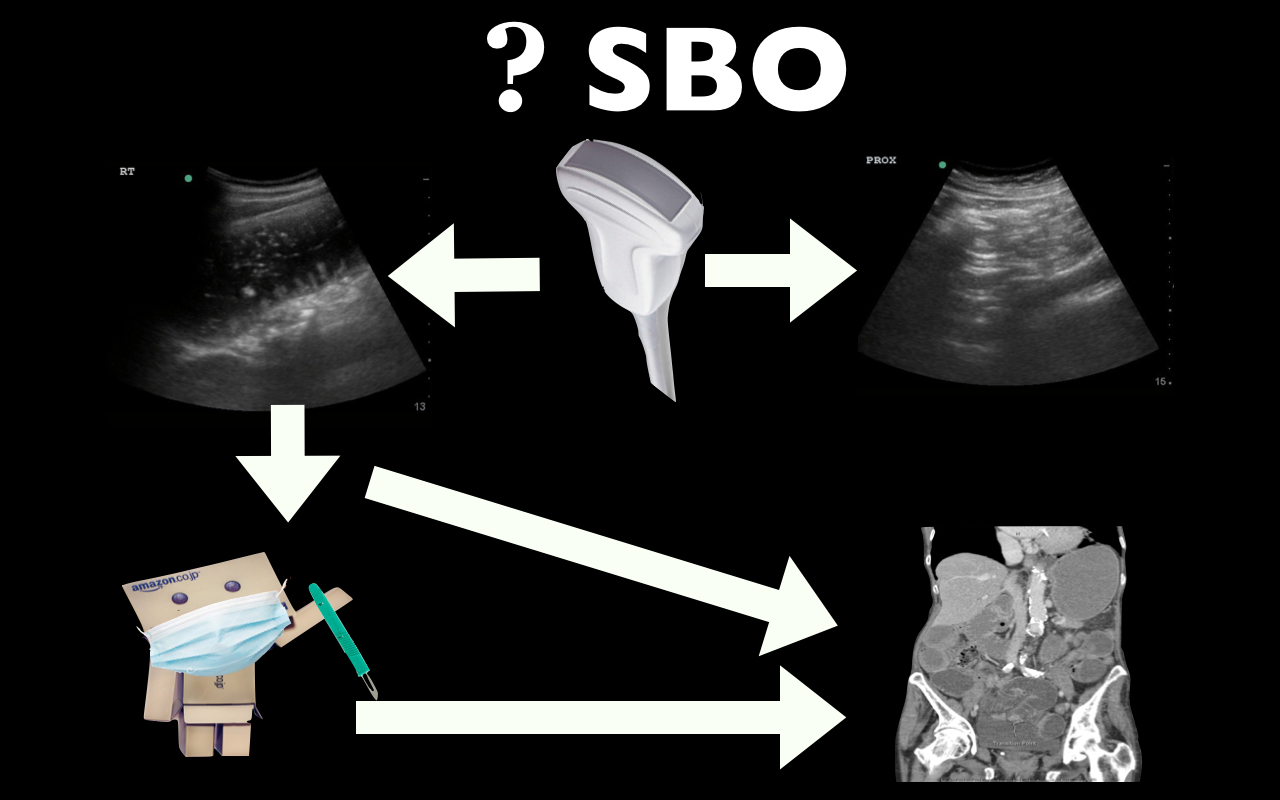

This week we’re covering Dr. Jacob Avila’s post on ultrasound for small bowel obstruction (SBO) located at Ultrasound of the week. He has an accompanying video on 5minSono.

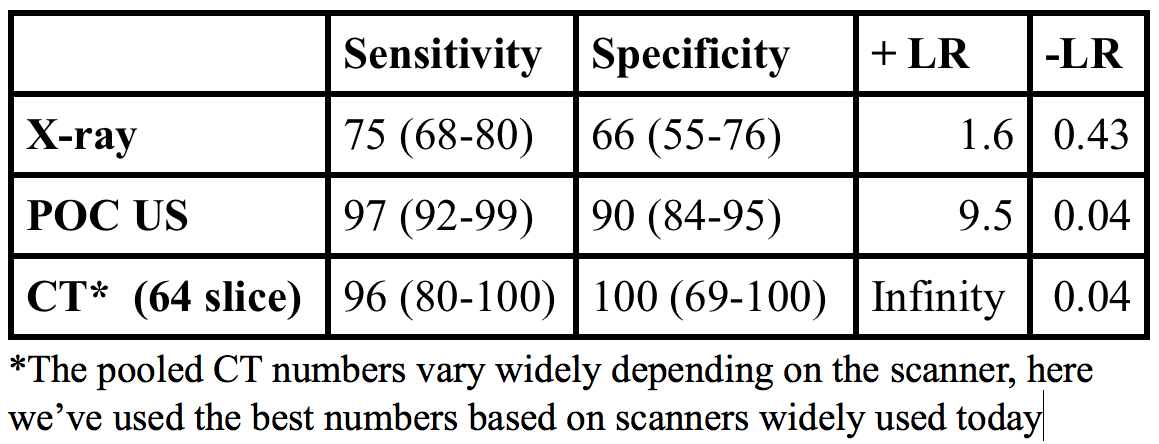

Point of care ultrasound has good operating characteristics for diagnosis of SBO with a LR+ 9.5, LR- 0.04, far better than abdominal x-ray [1].

What to look for:

- Dilated loops of bowel > 2.5 cm in diameter

- Additional clues: “To and fro” peristalsis

- The piano key sign, Tanga sign

Problems with abdominal x-ray:

- Rosen’s: Abdominal x-rays are “diagnostic in approximately 50 to 60% of cases of SBO, equivocal in 20 to 30%, and normal, nonspecific, or misleading in 10 to 20%” [2].

- American College of Radiology: they can “prolong the evaluation period … while often not obviating the need for additional examinations, particularly CT” [3].

Limitations:

- While ultrasound can diagnose SBO, there is little evidence to suggest that we can identify transition points or strangulation/necrosis. As such, there can still be a role for CT scan, particularly in first time SBO to identify a transition point.

- The EAST guidelines acknowledge the utility of ultrasound yet this practice is far from accepted in the surgical community. Surgical colleagues will likely still want concrete imaging such as an x-ray or CT; however, ultrasound performed concurrent with the history and physical may speed up patient’s disposition to definitive care/imaging.

More FOAM on the topic:

- SBO – A Likely Story?

- SBO Ultrasound Presentation

- Ultrasound Podcast Episode 36 – SBO

- Boring EM – Bowel Sounds

The Bread and Butter

We cover key points on SBO and Acute Mesenteric Ischemia from Rosenalli, that’s Tintinalli (7e) Chapter 86; Rosen’s (8e) Chapter 92. But, don’t just take our word for it. Go enrich your fundamental understanding yourself.

Small Bowel Obstruction

Etiology of intestinal obstruction: “HANG IV.” Hernia, Adhesions (most common cause), Neoplasm, Gallstone ileus, Intussusception, Volvulus

Treatment

- Intravenous fluids – resuscitate the patient!

- Antiemetics. If a patient is compromising their airway, an aspiration risk, or vomiting despite antiemetics, consider the use of a nasogastric tube. Shockingly, “use of nasogastric decompression is considered dogma by many emergency physicians and surgeons, its effect in decreasing the duration of SBO has scant support in the medical literature” [2, 5]. This point demonstrates that SBO is not a monolithic disease entity but a spectrum of pathology with variable treatments depending on patient’s sickness.

- Antibiotics that cover gram-negative and anaerobic organisms

- Admit. Most of these patients will likely go to the surgical service; however,

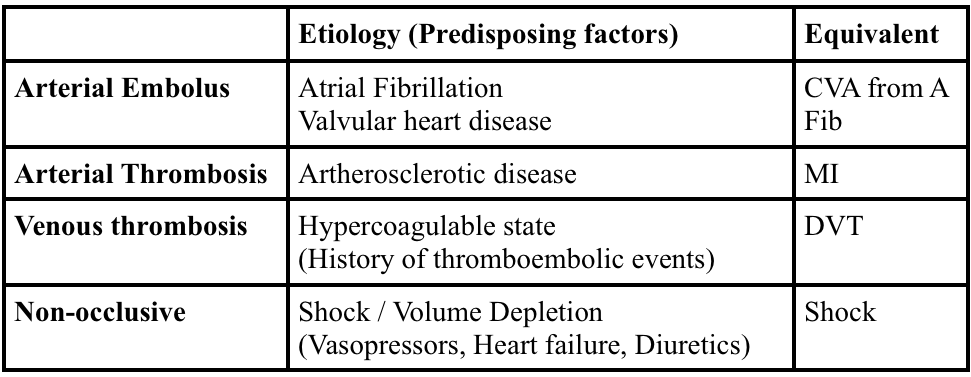

Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions (scroll for answers)

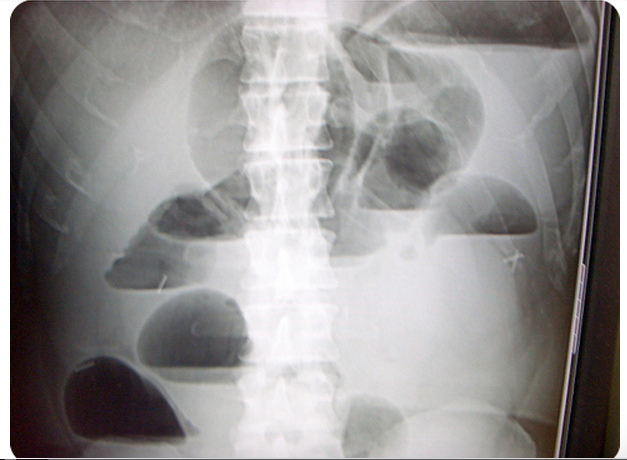

Question 1. A 73-year-old man presents with vomiting and abdominal pain for 2 days. The patient has a remote history of cholecystectomy and appendectomy. Examination reveals a markedly distended abdomen and absent bowel sounds. Lab studies show an elevated WBC count and a lactate of 4.3 mmol/L. An abdominal radiograph is obtained that is shown below. [polldaddy poll=8607202]

Question 2. An 87-year-old woman presents with worsening abdominal pain over the last 24 hours. She has minimal tenderness on examination but an elevated lactic acid. An abdominal CT Scan demonstrates mesenteric ischemia. [polldaddy poll=8607198]

References:

1. Taylor MR, Lalani N. Adult small bowel obstruction. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):528–44.

2. Roline CE, Reardon RF. “Disorders of the Small Intestine. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. 8th ed. pp 1216-1224.e2.

3. Ros PR, Huprich JE. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on suspected small-bowel obstruction. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3:(11)838-41.

4. Vicario SJ, Price TG. “Bowel Obstruction and Volvulus.” Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 7th ed. pp 581-583.

5. Fonseca AL, Schuster KM, Maung AA, Kaplan LJ, Davis KA. Routine nasogastric decompression in small bowel obstruction: is it really necessary? Am Surg. 2013;79:(4)422-8.

Answers.

1. D. This patient presents with a high-grade small bowel obstruction (SBO) with evidence of bowel ischemia (elevated lactate). Mortality has fallen in the last century with aggressive surgical treatment (from 60% to 5%). The abdominal radiograph above shows multiple air-fluid levels consistent with an SBO. Radiographs are abnormal in 50-60% of cases and are more likely to demonstrate abnormality when the obstruction is high-grade versus partial. Two views (upright and supine or supine and decubitus) should be obtained. Mechanical obstruction refers to the presence of a physical barrier to the flow of intestinal contents. In a simple obstruction, the intestinal lumen is partially or completely obstructed causing intestinal distension proximally but does not cause compromise of the vascular supply. In a closed-loop obstruction, a segment of bowel is obstructed at two sequential sites usually by twisting on a hernia opening or adhesive band leading to compromise of blood flow eventually resulting in bowel ischemia. Ischemia may only be seen on CT scan or occasionally, on laparoscopy or laparotomy. However, an elevated lactate in the setting of an SBO is highly suggestive of intestinal ischemia. The presence of blood in stool (either gross blood or guaiac positive stools) also suggests the presence of ischemia or infarction. When compromise of the vascular supply is suspected, the patient should have an emergent surgical consultation for operative management. Immediate management should also include placement of a nasogastric tube for decompression of the proximal parts of the intestines, intravascular volume resuscitation and intravenous antibiotics when vascular compromise is suspected or confirmed. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (A) is considered complimentary to plain films and is more sensitive and specific. Additionally, CT scan can reveal the site and cause of obstruction. However, surgical evaluation of a high-grade SBO should not be delayed for advanced imaging. Colonoscopy (B) is not indicated in small bowel obstruction. There is an increased risk of perforation. An enema and polyethylene glycol (C) is the treatment for constipation, and may worsen the outcome in patients with high-grade bowel obstruction.

2. Arterial emboli account for more than 50% of cases of mesenteric ischemia. The classic presentation of mesenteric ischemia is abdominal pain out of proportion to examination. Most commonly, thrombi develop in the left ventricle or atrium and embolize into the aorta. From the aorta, the emboli pass into one of the branches supplying the circulation to the gut. Thesuperior mesenteric artery is the most common site of embolization because of its large diameter and narrow angle of takeoff from the aorta. Mesenteric ischemia usually involves the small intestine and sometimes the right colon. The large intestine has significantly more collateral flow and is not as susceptible to ischemia. Aortic dissection (A) may lead to mesenteric ischemia depending on the location of the dissection. It is also possible to have a primary dissection of the mesenteric blood supply (e.g. SMA).Primary arterial thrombosis (C) of the mesentery is much less common and arises from progression of underlying atherosclerotic disease. Patients will often have a history of intestinal “angina” or chronic mesenteric ischemia during which symptoms occur after eating when the gut requires additional blood supply which is limited by the atherosclerotic changes. Venous thrombosis (D) is the least common etiology of mesenteric ischemia and most commonly affects the superior mesenteric vein.