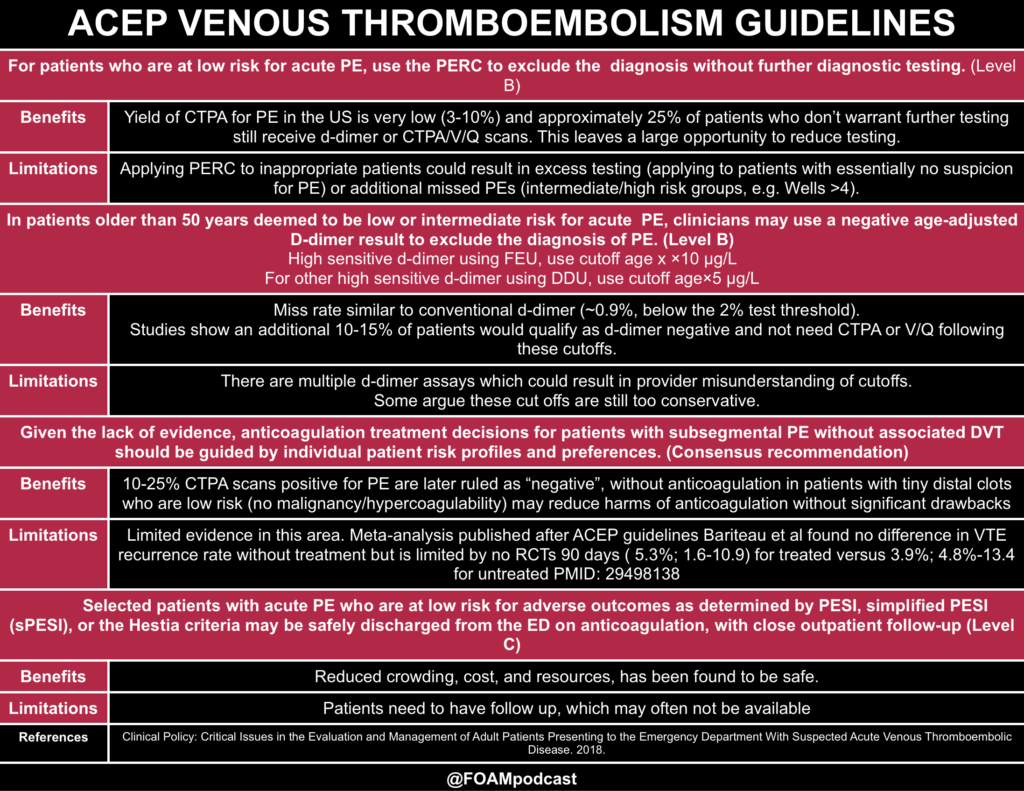

We cover the American College of Emergency Physicians clinical policy on Acute Venous Thromboembolic Disease (i.e. PE) [1]

Risk Stratification in Pulmonary Embolism

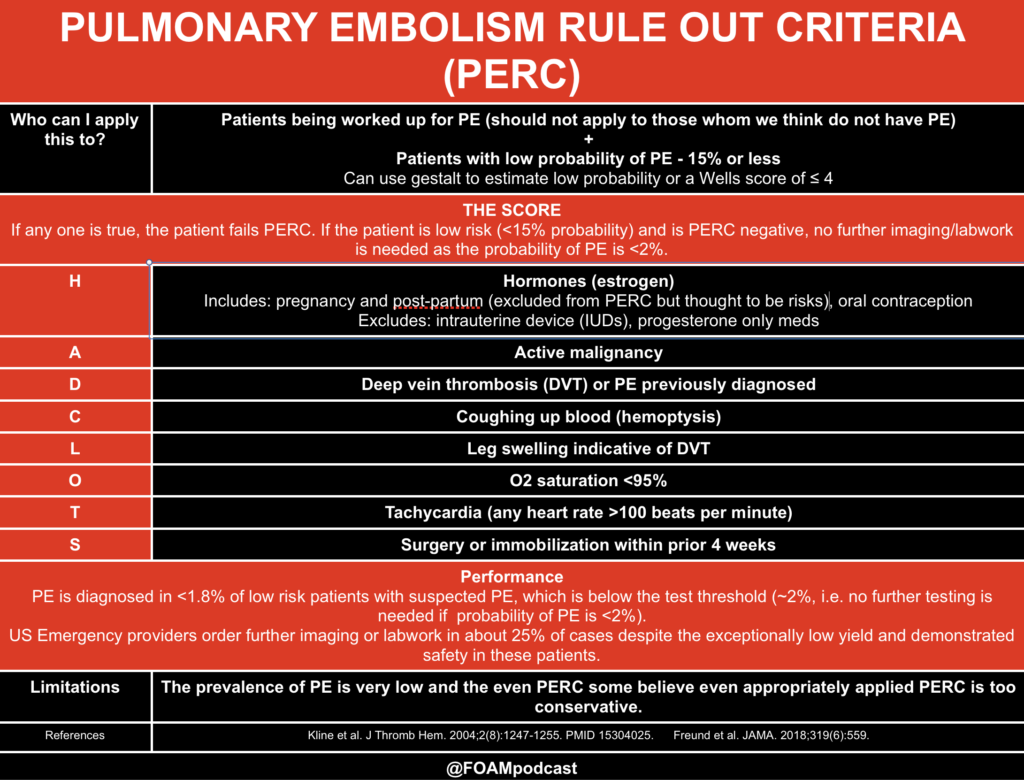

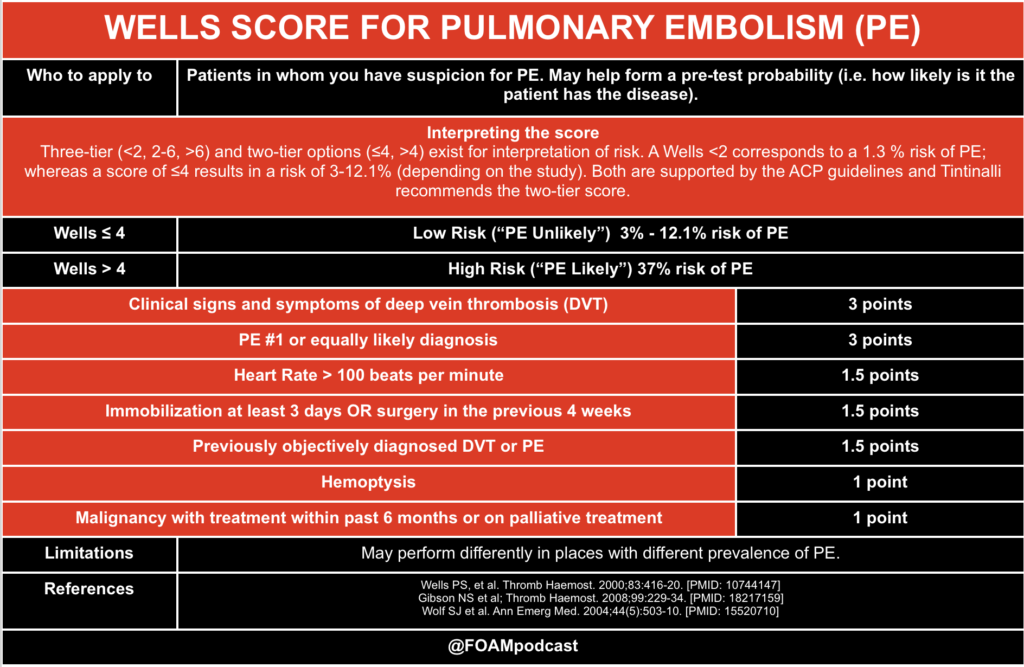

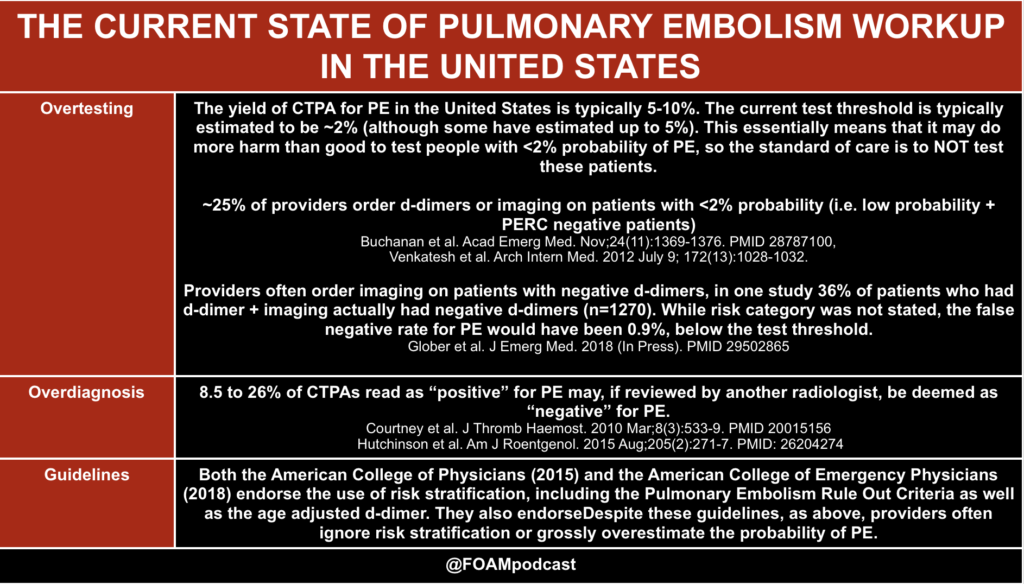

In the United States, the workup rate for PE is astonishingly high, with 1-2% of all ED patients receiving a CTPA for PE and a low yield (~5-10% of CTPAs are positive for PE). Thus, major medical societies such as ACEP and the American College of Physicians recommend the use of risk stratification tools [1,2]. For some reason, approximately 25% of patients who are low risk AND PERC negative still receive d-dimer or imaging for PE, despite the risk of PE being exceptionally low. To be clear, use of clinical decision tools are not mandatory and do not necessarily perform better than clinical gestalt [9]. These tools may serve as a “reality check” for some, reminding them that patients may be at lower risk of PE than they think

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

References:

- Acute Venous Thromboembolic Disease. ACEP Clinical Policy. 2018

- Raja AS et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: Best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701–11.

- Bariteau A, Stewart LK, Emmett TW, Kline JA. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Outcomes of Patients With Subsegmental Pulmonary Embolism With and Without Anticoagulation Treatment. Acad Emerg Med. 2018 (in Press)

- Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Kabrhel C, Richman PB, Courtney DM. Clinical criteria to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost JTH [Internet]. 2004;2(8):1247–55.

- Buchanan I, Teeples T, Carlson M, Steenblik J, Bledsoe J, Madsen T. Pulmonary Embolism Testing Among Emergency Department Patients Who Are Pulmonary Embolism Rule-out Criteria Negative. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(11):1369–76.

- Courtney DM, Miller C, Smithline H, Klekowski N, Hogg M, Kline JA. Prospective multicenter assessment of interobserver agreement for radiologist interpretation of multidetector computerized tomographic angiography for pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(3):533–9.

- Wells PS, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:416-20. [PMID: 10744147]

- Gibson NS et al; Christopher study investigators. Further validation and simplification of the Wells clinical decision rule in pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:229-34. [PMID: 18217159]

- Penaloza A, Verschuren F, Meyer G, Quentin-Georget S, Soulie C, Thys F, et al. Comparison of the Unstructured Clinician Gestalt, the Wells Score, and the Revised Geneva Score to Estimate Pretest Probability for Suspected Pulmonary Embolism. Ann Emerg Med [Internet]. 2013 Aug;62(2):117–124.e2. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0196064412017180