(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

We cover a trick of the trade from Dr. Brian Lin, posted on the Academic Life in Emergency Medicine (ALiEM site) on hemostasis in finger tip avulsions. Dr. Lin also has his own excellent FOAM site on all things laceration – LacerationRepair.com.

We also cover FOAM on dogma of wound care from Dr. Ken Milne’s The Skeptic’s Guide to Emergency Medicine, Episode #63

Core Content – Wounds and Laceration Care

Tintinalli (7e) Chapter 44, “Wound Preparation.” Rosen’s (8e) Chapter 59, “Wound Management Principles.”

Laceration Care:

- Use gloves, they don’t have to be sterile [1].

- Anesthetize (lidocaine with epinephrine is just fine).

- Irrigate copiously. It’s estimated that one needs ~60 mL/centimeter of wound or at least 200 mL.

- You can irrigate with water or saline. Potable tap water is fine [2,3]

- For a cornucopia of laceration techniques visit LacerationRepair.com

- No clear “golden period” for laceration repair [4-6]. Rosen’s and Tintinalli recommend using clinical judgment as a guide.

Risks for Infection:

- Diabetes

- Length of laceration (>5 cm)

- Location of the wound

- Degree of contamination [6]

Age of wound when approximated (i.e. “golden period”) has not been found to be an independent risk factor). Rosen’s sites use of epinephrine as a risk but only cites a paper by Barker et al from 1982 in which tetracaine/epinephrine/cocaine was applied to wounds inflicted by researchers that were inoculated by s. aureus.

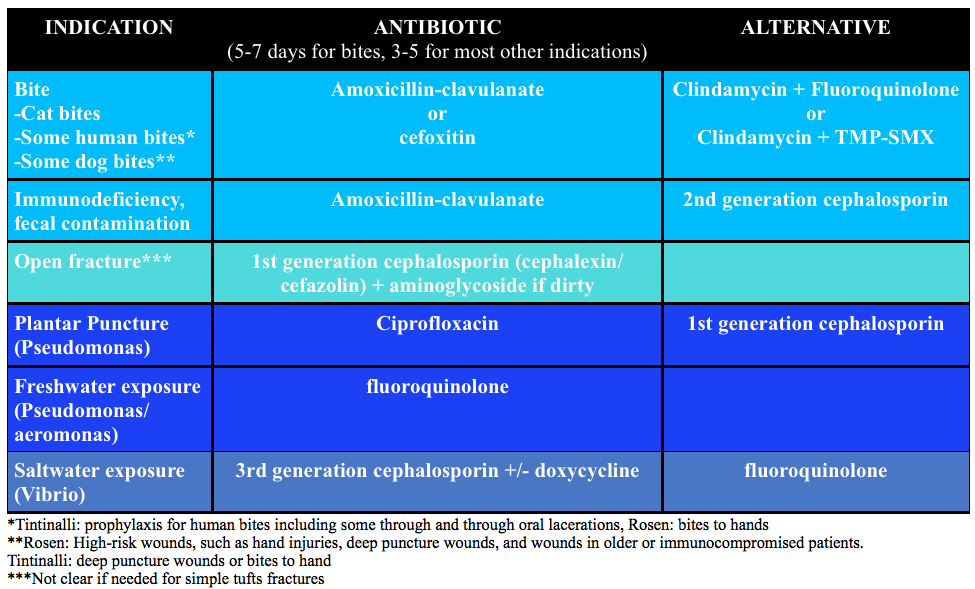

Prophylactic antibiotics:

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. An 18-year-old woman presents with a laceration to her face from a dog bite that occurred 24 hours ago. The patient owns the dog. Examination reveals a 4 cm laceration to the left cheek with no signs of infection. [polldaddy poll=9180209]

Question 2. A 30-year-old man presents with a 2 cm linear laceration through his right eyebrow that he sustained after hitting his head on the kitchen cabinet. You determine that the wound will require repair with sutures. [polldaddy poll=9180210]

Answers

- Mammal bites to any part of the body should be copiously irrigated and explored followed by an assessment for primary closure. In this patient, primary closure is recommended as the laceration is on the face. Canine bites often involve laceration as well as crush injury to tissue depending on the size of dog. The presence of a crush injury may make primary wound repair difficult. Additionally, devascularization of the tissue may make primary closure contraindicated as the risk of infection increases. Classically, it was taught that lacerations sustained from dog bites should be irrigated, given antibiotics and not primarily repaired because of these risks. However, more recent literature has shown that the risk of infection was no different for primary closure versus healing by secondary intention. Additionally, if the laceration is to a cosmetic area like the face, primary repair should be attempted. As with any laceration, tetanus status should be updated. Copious irrigation and wound exploration is central to good wound care. Exploration should pay particular attention to the presence of foreign bodies especially teeth, which may break off during the bite. Antibiotics (A & C) are not routinely needed for dog bites despite classic teaching. Antibiotics should be reserved for patients with signs of infection, multiple comorbidities or large wounds with gross contamination. If antibiotics are given, they should primarily cover Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, as these are the predominant organisms in the canine oral cavity. Eikenella and Pasturella are less commonly responsible for infections. Irrigation and antibiotics alone (A) would be indicated for dog bites that are grossly infected or have large defects that cannot be primarily closed. Wound closure and antibiotics without irrigation (D) is also contraindicated as copious irrigation is central to proper wound management.

- A pair of clean, non-sterile gloves can be worn by the physician (and any assistants) during laceration repair. The use of sterile gloves has not been proven to be associated with lower infection rates and is not required. Wounds must be prepped prior to closure. This generally involves cleaning and draping the wound, providing local or regional anesthesia, copious irrigation and exploring the wound to evaluate the integrity underlying structures and identify any foreign bodies. The skin surrounding a wound should be cleansed with either 10% povidone-iodine (C) or chlorhexidine gluconate solution. In general, these commercially available antiseptics should not be used for wound irrigation, as they can be toxic to the tissues. Irrigation should then follow with copious amounts of tap water or saline (at least 250 mL). This is best achieved with a large volume syringe attached to an 18-gauge needle or another commercially available irrigation device that achieves adequate pressure for irrigation. Alternatively, patients can irrigate at the sink if the laceration is in area that allows for this. Shaving of hair been shown to increase the risk of infection and should generally be avoided. It is best to apply a small amount of petroleum- or water-based lubricant to the hair to keep it out of the wound. Alternatively, hair can be clipped with scissors when necessary. Eyebrows (B) in particular should not be shaved as they provide anatomic landmarks that aid in wound approximation and removal results in poor short- and long-term cosmetic effect. In general, non-complex facial wounds are closed with nonabsorbable suture material, such as nylon or polypropylene. Most commonly this will be done with 6-0 suture, as it provides the best cosmetic effect. The use of 3-0 (D) and 4-0 suture is reserved for repair of fascia or wounds that are under high stress, such as those that overly major joints or involve the scalp.

References:

- Perelman VS, Francis GJ, Rutledge T, et al. Sterile versus nonsterile gloves for repair of uncomplicated lacerations in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of emergency medicine. 43(3):362-70. 2004

- Fernandez R, Griffiths R. Water for wound cleansing. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2:CD003861. 2012.

- Weiss EA, Oldham G, Lin M, Foster T, Quinn JV. Water is a safe and effective alternative to sterile normal saline for wound irrigation prior to suturing: a prospective, double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. BMJ open. 3(1):. 2013.

- American College of Emergency Physicians: Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients presenting with penetrating extremity trauma. Annals of emergency medicine. 33(5):612-36. 1999. [pubmed] **A past policy, no current clinical policy

- Zehtabchi S, Tan A, Yadav K, Badawy A, Lucchesi M. The impact of wound age on the infection rate of simple lacerations repaired in the emergency department. Injury. 43(11):1793-8. 2012.

- Quinn JV, Polevoi SK, Kohn MA. Traumatic lacerations: what are the risks for infection and has the ‘golden period’ of laceration care disappeared? Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 31(2):96-100. 2014.