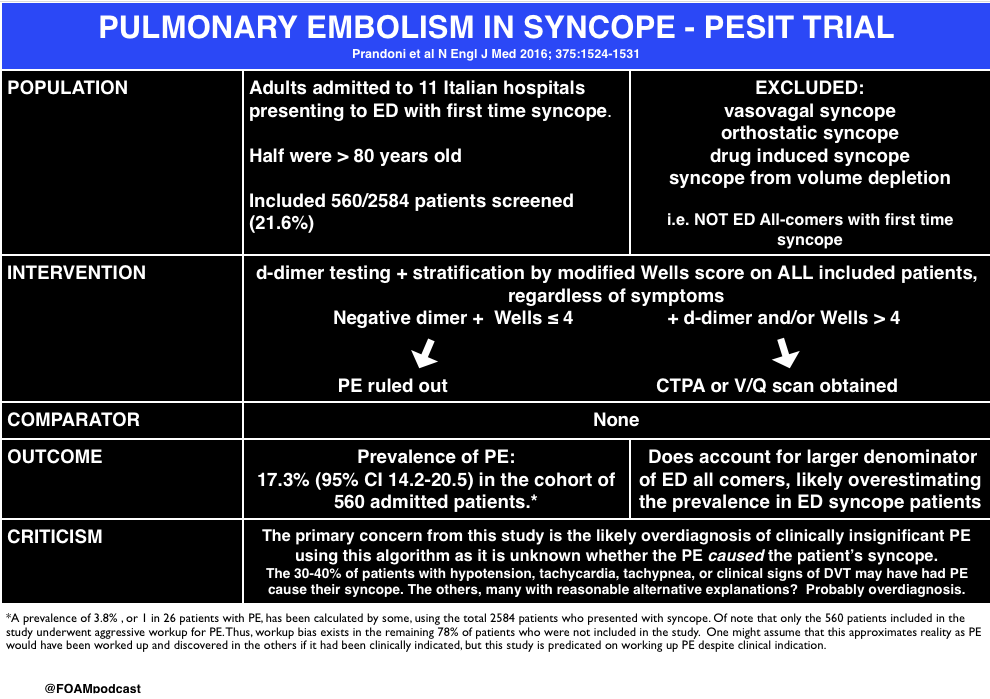

The PESIT study in the New England Journal of Medicine stirred up controversy in the FOAM world earlier in October 2016. In this episode we cover the following posts on this article on pulmonary embolism in syncope:

Core Content

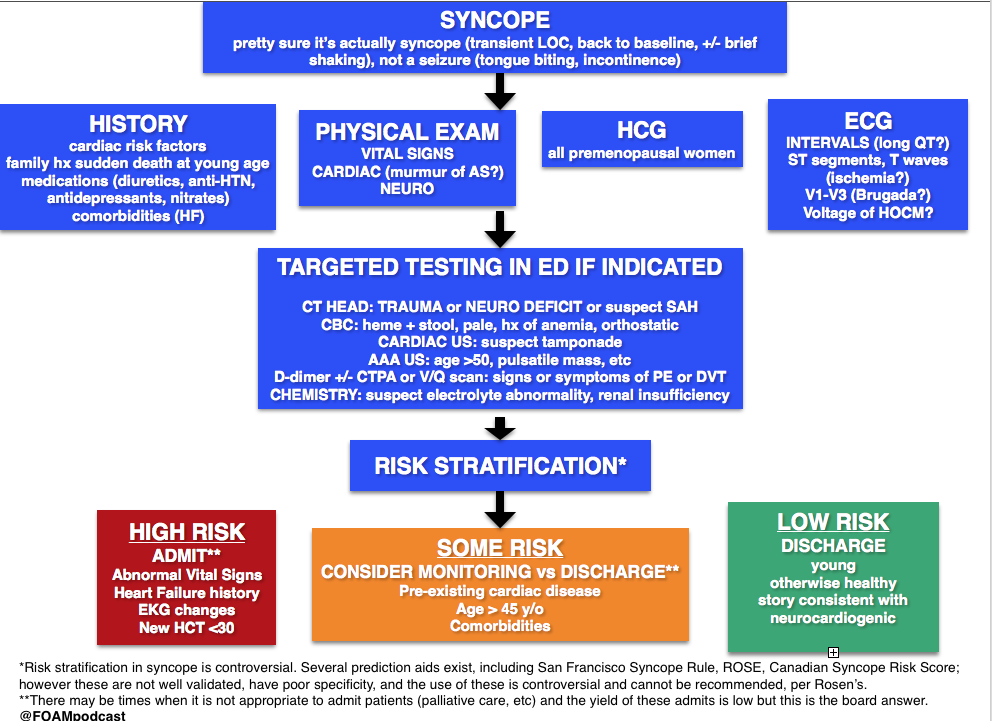

We delve into core content on syncope usingRosen’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) and Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) Chapter 52

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

An 83-year-old is being evaluated in the emergency department after an episode of syncope. The woman was preparing dinner when she felt her heart start to race. The next thing she remembers is waking up on the floor. She experienced a similar episode about three weeks ago. She has never had anything like this before. Her past medical history is remarkable for hypertension, hyperlipidemia and hypothyroidism. Her medications include lisinopril, atorvastatin and levothyroxine. On physical exam her blood pressure is 142/83, heart rate 76/min, and respiration rate 13/min. Cardiac auscultation reveals no murmur. The remainder of her physical exam is normal. Electrocardiogram reveals normal sinus rhythm with left axis deviation. No cardiac rhythm abnormalities are detected. What is the most likely etiology of this patient’s syncope?

A. Aortic stenosis

B. Cardiac dysrhythmia

C. Orthostatic hypotension

D. Vasovagal

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

B. Cardiac dysrhythmia is the most likely cause of this woman’s syncope. Cardiac dysrhythmias are a common cause of syncope in the elderly population. It is characterized by a brief or absent prodrome and palpitations immediately preceding the event. Several episodes over a short period of time in someone with no history of syncope suggest a dysrhythmia. Given this patient’s short prodrome, palpitations and history of a previous similar event makes a cardiac dysrhythmia the most likely etiology.

Aortic stenosis (A) is unlikely the cause of her syncope. Aortic stenosis is associated with a crescendo-decrescendo systolic ejection murmur. Syncope related to aortic stenosis typically occurs during exertion and is associated with very severe disease. This patient’s syncopal episode occurred while stationary. Additionally, she has no systemic symptoms of aortic stenosis.Vasovagal (D) is the most common cause of syncope in the general population. It is usually triggered by provoking factors such a blood draw or an intense emotion. Prodromal symptoms include feeling warm, sweating, nausea, and pallor. This woman does not report any of these symptoms. Orthostatic hypotension (C) causes syncope upon assuming an upright position from supine or sitting. It is often caused by hypovolemia, medications or autonomic nervous system disorders. This woman was standing while preparing dinner making orthostatic hypotension unlikely.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

An 18-year-old woman presents after having a syncopal episode. She is complaining of a 2-day history of lower abdominal pain and vaginal spotting. Her BP is 86/42, HR is 128, RR is 18 breaths, and oxygen saturation is 99% on room air. She is drowsy, but answers questions appropriately. What is the most appropriate next step in management?

A. Establish large-bore IV access and administer an IV fluid bolus

B. Initiate rapid sequence induction and orotracheal intubation

C. Perform a bedside urine pregnancy testing

D. Perform an ultrasound of the abdomen to assess for free fluid

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

A. The patient is hypotensive and tachycardic. She is suffering from hypovolemic shock secondary to a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Therefore she requires immediate intravenous access and volume resuscitation with Lactated Ringer’s or normal saline. Emergency Department management of unstable patients includes rapid assessment of the ABC’s (Airway, Breathing, Circulation). This patient is phonating, has a respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute and an oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. There is no concern that her airway or breathing is in immediate jeopardy, therefore she would not require immediate rapid sequence induction and orotracheal intubation (B). Although a bedside pregnancy test (C) and abdominal ultrasound (D) would help make a diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy, the next step would be to resuscitate the patient.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References

- De Lorenzo RA. “Syncope.” Chapter 15. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (8 ed). pp 131-145

- Chapter 52. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Review (8 ed).

- Serrano LA, Hess EP, Bellolio MF et al. Accuracy and Quality of Clinical Decision Rules for Syncope in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 56(4):362-373.e1. 2010.