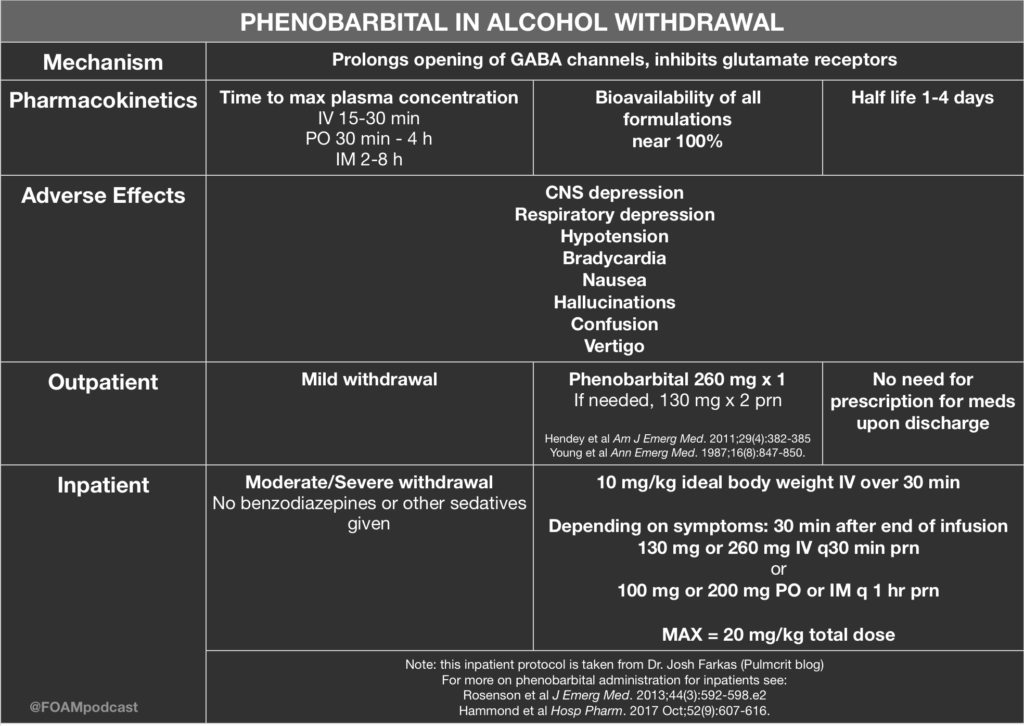

Over at the Pulmcrit blog, Dr. Josh Farkas has proposed the use of phenobarbital monotherapy for the treatment of ethanol withdrawal. He argues that phenobarbital has the following advantages:

- Superior neurochemistry

- Reliable – some patients will be resistant to benzos but this does not happen as much with phenobarbital

- Predictable pharmacokinetics

Core Content

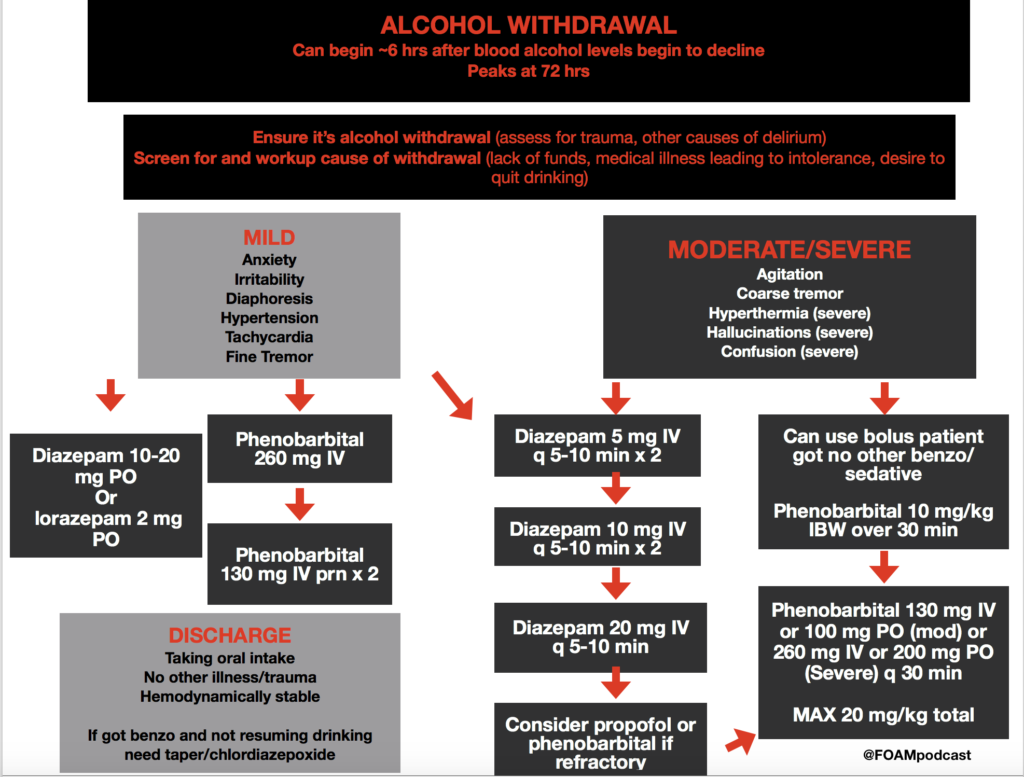

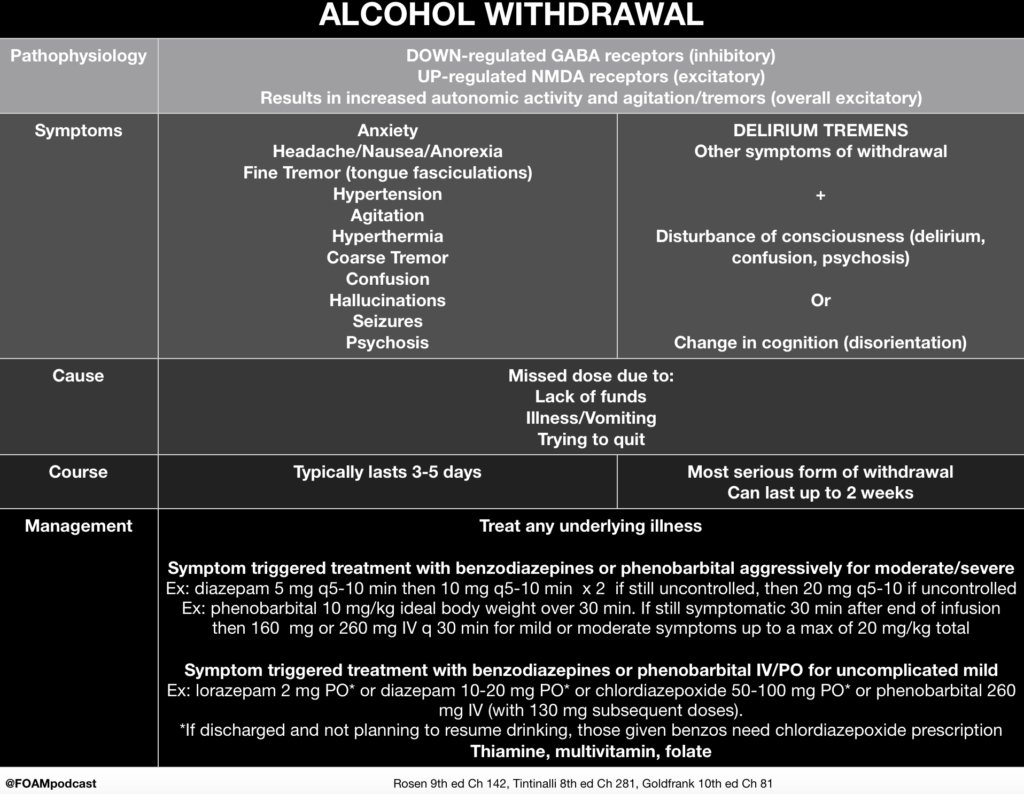

We cover alcohol withdrawal using Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (9th ed) Chapter 142 , Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine (8th ed) Chapter 292, and Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies (10th ed) Chapter 81 as guides.

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 49-year-old man presents to the Emergency Department complaining of sweating and tremors. The patient drinks a bottle of liquor per day and stopped suddenly because of a pending court case. His last alcoholic drink was 3 days ago. On physical examination, his blood pressure is 168/105 mm Hg, pulse rate is 106/minute, respirations are 22/minute, and temperature is 99.3°F. The patient appears agitated and restless with a visible tremor of bilateral hands. The triage team ordered folic acid, thiamine, and a multivitamin. Which of the following is the most appropriate disposition?

A. Admit the patient and start diazepam

B.Admit the patient and start disulfiram

C.Discharge the patient with a prescription for diazepam

D.Discharge the patient with a prescription for disulfiram

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”] A. Admit the patient and start diazepam is the correct disposition because this patient is suffering from alcohol withdrawal, which potentially can be fatal. Withdrawal symptoms occur when a patient has alcohol use disorder and has developed a tolerance to alcohol, where an increased amount of alcohol is needed to achieve the desired effect. When tolerance has developed, cessation leads to withdrawal. Early symptoms of alcohol withdrawal include anxiety, irritability, headache, tremor, tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and hyperactive reflexes. Seizures (usually grand mal) can develop between 12-24 hours after withdrawal starts. After 24-72 hours, life-threatening delirium tremens may occur, which manifests with signs of altered mental status, hallucinations and marked autonomic instability. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal involves giving a benzodiazepine (e.g. diazepam) until symptoms lessen and then tapering the dosage over days to weeks. Thiamine, folic acid, and vitamin B12 are also administered and any electrolyte abnormalities are corrected (typically low potassium and magnesium). Following withdrawal, the patient should be referred to support groups. Long term medication used to deter use of alcohol include naltrexone, disulfiram, and acamprosate.

Admit the patient and start disulfiram (A) is incorrect because the patient needs a benzodiazepine medication to prevent delirium tremens and potentially fatal consequences. Disulfiram is a medication used in some patients for long-term adherence to alcohol abstinence. Ingestion of alcohol while taking disulfiram causes copious vomiting and potentially more severe reactions. Discharge the patient with a prescription for diazepam (C) or disulfiram (D) is incorrect because alcohol withdrawal is potentially lethal and this patient should be admitted.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References:

- “Alcohol Related Diseases.” Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. 9th ed. Chapter 142, 1838-1851.e1

- “Substance Use Disorders.” Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. 9th ed. Chapter 281.

- “Ethanol Withdrawal.” Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 10th ed. Chapter 81.

- Hendey GW, Dery RA, Barnes RL, Snowden B, Mentler P. A prospective, randomized, trial of phenobarbital versus benzodiazepines for acute alcohol withdrawal. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(4):382-385.

- Young GP, Rores C, Murphy C, Dailey RH. Intravenous phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal and convulsions. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16(8):847-850.