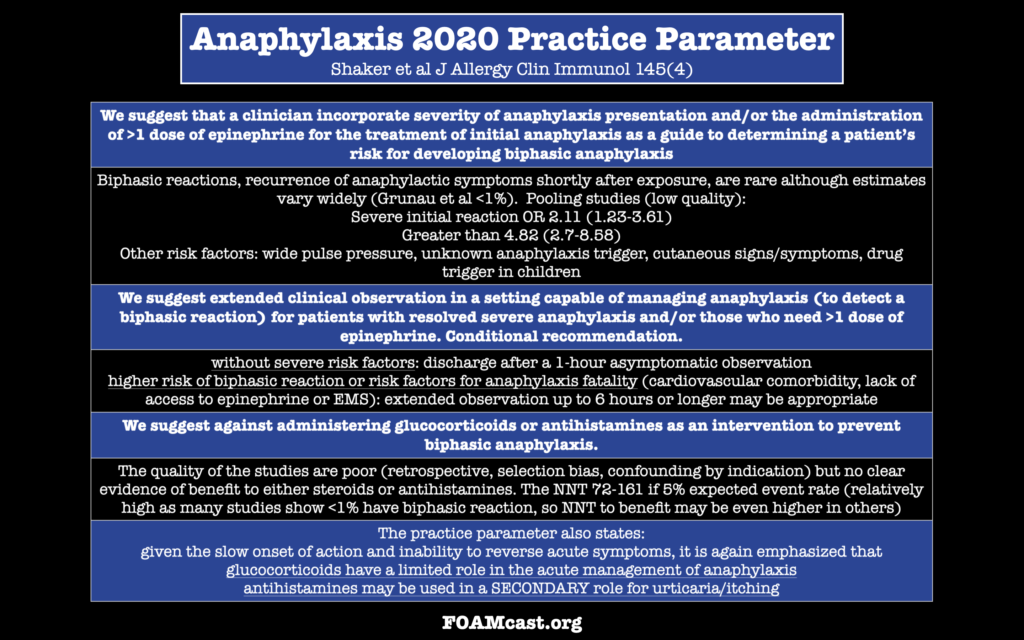

We review the AAAAI 2020 Anaphylaxis Update

We are at SMACC in Sydney, Australia, thanks to the Rosh Review, delivering updates from the conference to your earbuds. Today we cover resuscitation pearls.

Bougie vs Standard Stylet in emergency department (ED) rapid sequence intubation (RSI) – Brian Driver vs Rich Levitan

Driver BE, Prekker ME, Cole JB. Use of a Bougie for Intubation in an Emergency Department-Reply. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1603-1604.

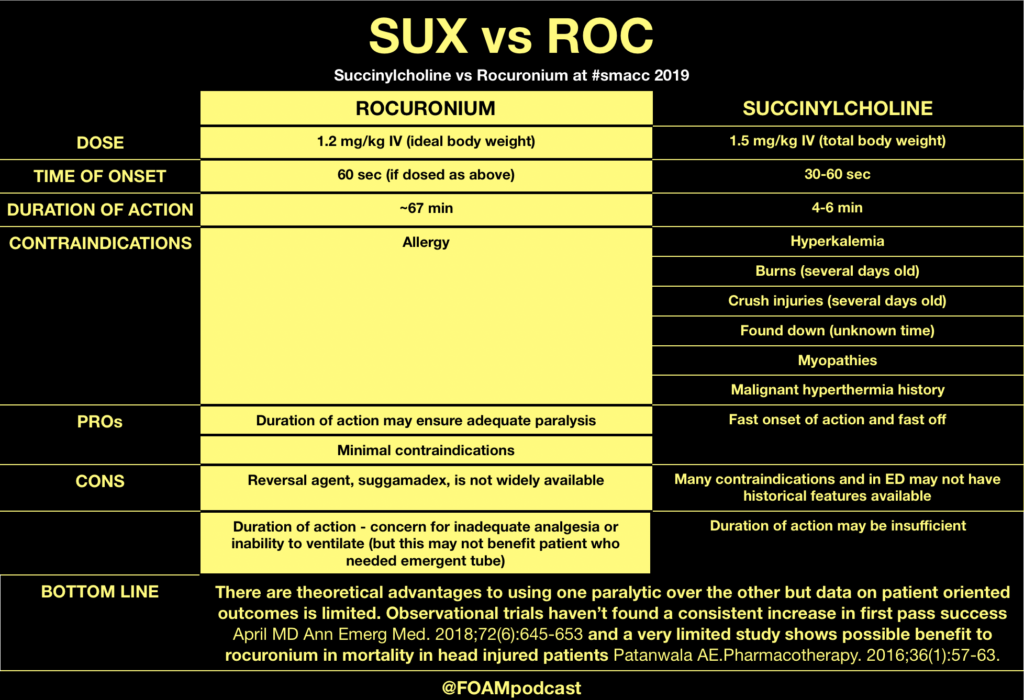

Rocuronium vs Succinylcholine Debate – Billy Mallon and Reuben Strayer

The Crashing Asthmatic – Haney Mallemat

Special thanks to the Rosh Review for sponsoring us to come to SMACC to bring updates to y’all!

We co-hosted (with John Vassiliadis) the #smacc EM Updates half-day conference. We had amazing speakers. Salim Rezaie spoke on TXA for Everything, Ken Milne spoke on hot papers from 2018, and we learned about when ultrasound may be helpful in pediatric lumbar punctures. In addition, Jeremy spoke on what is usual care in sepsis and Lauren spoke on pulmonary embolism: the next generation. In this short podcast we highlight some of our other talks.

Aidan Baron (@Aidan_Baron) on Prehospital Updates in Cardiac Arrest

This talk focused on focusing on things that are most likely to make a difference in OHCA (bystander CPR and defibrillation) rather than on fun interventions like intubation and adrenaline (epinephrine). Aidan suggests that the future debates and questions in OHCA will be largely philosophical – what outcomes do we care about: neuro intact survival or ROSC or survival?

Low-Risk Chest Pain and the HEART Score by Barbra Backus

Modified Heart Score (redefining the T or troponin based on newer assays) results in a NPV of 99.8% and classifies 48% of patients as low-risk.

Clinically Relevant Adverse Cardiac Events (CRACE) is way less common than major adverse cardiac events (MACE). HEART score of ≤3 ? CRACE is 0.05%

Hot Literature in 2019

Lemkes JS, Janssens GN, van der Hoeven NW, et al. Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest without ST-Segment Elevation. N Engl J Med. 2019;NEJMoa1816897

Pluymaekers NAHA, Dudink EAMP, Luermans JGLM, et al. Early or Delayed Cardioversion in Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med .2019;NEJMoa1900353.

Special thanks to the Rosh Review for supporting our trip to SMACC!

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

We cover a Scancrit post on the Back Up Head Elevated (BUHE) intubation position. This post details a multicenter retrospective observational study by Khandelwal et al in Anesthesia & Analgesia

Population: 528 adults undergoing emergent intubation

Intervention: Head up at least 30 degrees during intubation

Control: Supine intubation

Primary Outcome: Occurrence of intubation related complication (difficult intubation: >3 attempts or prolonged intubation, hypoxemia, esophageal intubation, or pulmonary aspiration) – 22.6% in supine group vs 9.3% in the head elevated position. Absolute difference of 13.3%

Limitations: Did not look at emergency department intubation. More experienced intubators used the BUHE positioning, which could confound the reduction in intubation related complications [1].

BUHE or Head Elevated Laryngoscopy Position (HELP) has also been found to

Note: in patients with possible spinal injuries, one may use reverse trendelenberg (or forego the back up head elevated position)

Core Content

We delve into core content on the esophagus using Rosen’s (8th ed) Chapter 71 and Chapter 77 in Tintinalli (8th ed)

DYSPHAGIA

Emergent conditions may include stroke (most common cause), myasthenia/botulism/or other neuromuscular problems (may also have concomitant respiratory failure). Many causes do not need emergent workup.

ESOPHAGEAL FOOD BOLUS

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

An 87-year-old woman presents to the ED after her caregiver witnessed the patient having difficulty swallowing over the past 2 days. The patient is having difficulty with both solids and liquids. She requires multiple swallowing attempts and occasionally has a mild choking episode. She has no other complaints. Your exam is unremarkable. Which of the following is the most likely cause of her condition?

A. Achalasia

B. Cerebrovascular accident

C. Esophageal neoplasm

D. Foreign body

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

B. Cerebrovascular accident. Dysphagia can be divided into two categories: transfer and transport. Transfer dysphagia occurs early in swallowing and is often described by the patient as difficulty with initiation of swallowing. Transport dysphagia occurs due to impaired movement of the bolus down the esophagus and through the lower sphincter. This patient is experiencing a transfer dysphagia. This condition is most commonly due to neuromuscular disorders that result in misdirection of the food bolus and requires repeated swallowing attempts. A cerebrovascular accident (stroke)that causes muscle weakness of the oropharyngeal muscles is frequently the underlying cause. Achalasia (A) is the most common motility disorder producing dysphagia. It is typically seen in patients between 20 and 40 years of age and is associated with esophageal spasm, chest pain, and odynophagia. Esophageal neoplasm (C) usually leads to dysphagia over a period of months and progresses from symptoms with solids to liquids. It is also associated with weight loss and bleeding. Foreign bodies (D) such as a food bolus can lead to dysphagia, but patients are typically unable to tolerate secretions and are often observed drooling. These patients do not have difficulty in initiating swallowing.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

A 33-year-old man presents with dysphagia to both solids and liquids, with solids being worse than liquids. He describes a sensation of the food getting stuck in his chest. Occasionally, he needs to raise his arms above his head to help food pass into his stomach. His primary care doctor has been treating him for GERD over the previous six months, but his symptoms are getting worse. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Achalasia

B. Diffuse esophageal spasm

C. Schatzki ring

D. Zenker’s diverticulum

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

Achalasia This patient most likely has achalasia, which is an esophageal dysmotility disorder due to failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax. Dysphagia is the most common symptom. While all patients have dysphagia to solids, only two-thirds have liquid dysphagia. By standing after eating, straightening one’s back, or raising the arms above the head, the esophageal pressure increases, which can help emptying into the stomach. Symptoms usually begin with mild dysphagia in patients who are 20 to 40 years old; symptoms are usually progressive. Diffuse esophageal spasm (B) is a hypermotility disorder causing strong, uncoordinated peristaltic contractions that do not propel food effectively to the stomach. Dysphagia, regurgitation of food, and chest pain are commonly present. The dysphagia is intermittent and does not progress over time. A Schatzki ring (C) is a fibrous band-like structure in the distal esophagus that is the most common cause of dysphagia with solids. Patients typically do not experience difficulty with liquids. Zenker’s diverticulum (D) is an acquired disease that is due to an out-pouching in the mucosa of the pharynx. It typically occurs in individuals older than 50 years and can cause regurgitation, cough, and halitosis from food that becomes stuck in the diverticulum.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

[accordion]

[toggle title=”What are three common treatments for achalasia?” state=”Closed”]

Nitroglycerin to reduce lower esophageal sphincter tone, endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin into the muscle of the sphincter, and surgical myotomy. Diffuse esophageal spasm (B) is a hypermotility disorder causing strong, uncoordinated peristaltic contractions that do not propel food effectively to the stomach. Dysphagia, regurgitation of food, and chest pain are commonly present. The dysphagia is intermittent and does not progress over time. A Schatzki ring (C) is a fibrous band-like structure in the distal esophagus that is the most common cause of dysphagia with solids. Patients typically do not experience difficulty with liquids. Zenker’s diverticulum (D) is an acquired disease that is due to an out-pouching in the mucosa of the pharynx. It typically occurs in individuals older than 50 years and can cause regurgitation, cough, and halitosis from food that becomes stuck in the diverticulum.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References

(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

The FOAM realm has teamed with interest in a randomized trial in the ICU by Semler et al, the FELLOW trial. This trial randomized ICU patients undergoing intubation to receive 15L NC during intubation or usual care. The study found no difference in the primary outcome of the study, the difference between the mean lowest oxygen saturations between the two groups – 92% (IQR 84-99%) in the usual care vs 90% (IQR 80-96%) in the apneic arm (p=0.16). Critiques of this study can be found below:

Concerns echoed by these sources include the clinical importance of the primary outcome (not patient oriented) and that the study may have been underpowered to detect a true difference.

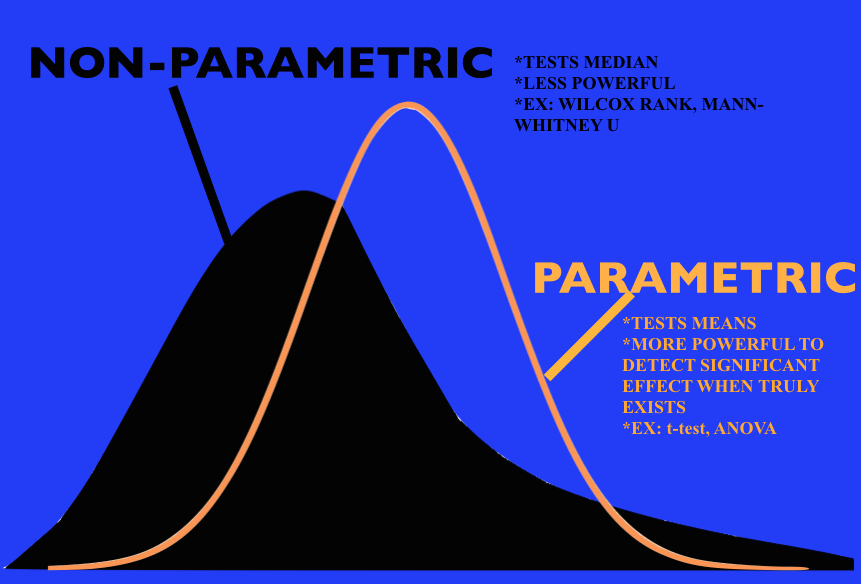

Statistical power – the chance that an experiment will result in a statistically significant. Three main things influence statistical power:

Also, oxygen saturation, a continuous variable, was appropriately analyzed by non-parametric (non normal distribution) means. Non-parametric means often have less power to detect a difference (aren’t as powerful). The FELLOW study was powered using parametric means, which is common practice (fewer programs can perform this) but may have also contributed to the studying having insufficient power to achieve the primary outcome.

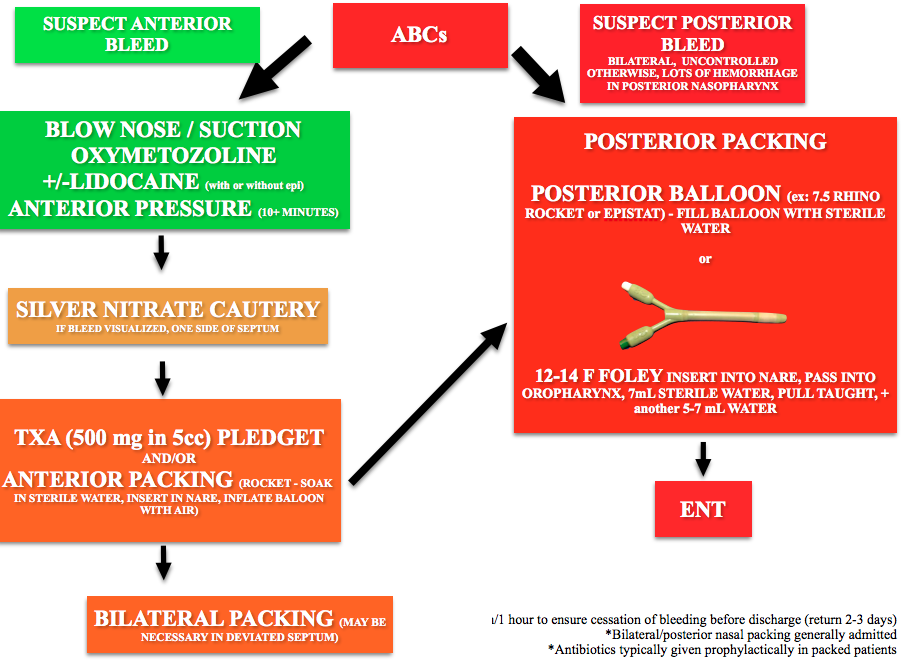

Core Content – Epistaxis and Sinusitis

Tintinalli (7e) Chapter 239, “Epistaxis, Nasal Fractures, and Rhinosinusitis.” Rosen’s (8e) Chapter 75, “Upper Respiratory Infection.”, “Otolaryngology”

Epistaxis

Causes:

Location: Anterior bleeds most common (Kiesselbach’s plexus). Posterior bleeds (sphenopalantine or carotid artery branches) more dangerous.

Treatment: (note: TXA is not in Rosen’s or Tintinalli, see Zahed and colleagues). Update 2/21/21: New trial shows no benefit of TXA

Sinusitis

Symptoms: mucopurulent nasal discharge,congestion, facial pain or pressure. Generally last 7-10 days and often viral. Diagnosis is predominantly clinical and does not routinely require CT scan [3]

Treatment: typically supportive care as most cases are self-limiting [2]. American Academy of Allergy Asthma Immunology Choosing Wisely : “Antibiotics usually do not help sinus problems, Antibiotics cost money. Antibiotics have risks” [4]. Despite these recommendations, provider still routinely prescribe antibiotics inappropriately [5].

Antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate) recommended if:

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

1.An 18-month-old girl presents to urgent care with profuse mucoid nasal discharge and cough. She has had nasal discharge for the past 2 weeks with no improvement from using a humidifier. She has also had fever for the past four days, with a Tmax of 103°F. She has not been able to attend daycare for the past week due to the fever and persistent symptoms. [polldaddy poll=9196746]

2. A 42-year-old man presents with facial pain. He reports pain over his cheeks and forehead with associated fever for the last 24 hours. On inspection of his nasal passages you not inflamed turbinates with green discharge. He is tender over palpation of the frontal and maxillary sinuses. [polldaddy poll=9196749]

Answers.

1.C. Acute sinusitis is a common illness of childhood, characterized by fever, cough, purulent nasal discharge, and nasal congestion. The most common cause of sinusitis is viral, which is best treated with supportive care. Acute bacterial sinusitis often follows a case of viral sinusitis. In young children, sinusitis may be present in the ethmoidal sinuses. The maxillary sinuses are present at birth, but are not pneumatized until 4 years of age. The sphenoid sinuses are present by age 5, and the frontal sinuses begin development at age 7-8. Due to this child’s persistent symptoms for more than 10-14 days, fever of greater than 102°F, and purulent nasal discharge for more than 3 consecutive days, the most likely diagnosis is acute bacterial sinusitis. The most common bacterial pathogens are Streptococcus pneumoniae (30%), nontypable Haemophilus influenzae (20%), and Moraxella catarrhalis (20%). Less common causes include other strains of streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and anaerobic bacteria. Initial treatment consists of low dose amoxicillin, which covers the most common bacterial pathogens. However, some children are at risk for resistant strains of bacterial pathogens, such as children in daycare, those less than 2 years of age, and those who have received antibiotics in the preceding 1-3 months. These children should be given amoxicillin-clavulanate with high dose amoxicillin. Children who fail initial therapy should also be escalated to high dose amoxicillin-clavulanate.Azithromycin (A) is an alternative antibiotic that can be used to treat sinusitis in older children. It would not be the first line therapy in this young child. Ceftriaxone (B) should be used in frontal sinusitis, complicated sinusitis (such as periorbital or orbital cellulitis) or in the setting of intracranial complications (such as epidural abscess, meningitis, or cavernous sinus thrombosis). Low dose amoxicillin (D) is the first line therapy in uncomplicated sinusitis, when the child does not have risk factors for resistant bacterial pathogens.

2. C. This patient has rhinosinusitis. Viral upper respiratory infections and allergic rhinitis are the most common causes of acute rhinosinusitis. Additional risk factors are ciliary immobility or dysfunction, structural abnormalities, immunocompromise, Patients with viral sinusitis are at risk of developing bacterial sinusitis as a consequence of the viral infection. Clinically patients with acute rhonisinusitis develop mucopurulent nasal discharge, facial or sinus pain, and nasal congestion. Symptoms of acute sinusitis typically progress over the first several days and spontaneously resolve after 7 to 10 days. It is difficult to distinguish clinically between viral and bacterial infection in the first several days of illness and antibiotic therapy is not recommended at this time. Management focuses on symptomatic treatment with pain management and decongestant therapy. Antihistamines may provide some benefit for patients with allergic rhinosinusitis. Decongestant therapy is available topically with agents like oxymetazoline. Systemic therapy includes pseudoephedrine. Saline nasal irrigation is beneficial for all forms of acute rhinosinusitis. Topical and systemic steroids are no longer recommended for acute sinusitis.A CT scan of the sinuses (A) is not necessary in this patient. Imaging is indicated when there are concerns for complications of cellulitis (e.g. cavernous sinus thrombosis, abscesses, orbital involvement) or invasive fungal infections. ENT consultation (B) is not necessary for uncomplicated cellulitis. A prescription for amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (D) is not indicated in the first several days of illness because of the likelihood this is viral. Without improvement after symptomatic therapy or progression to chronic sinusitis antibiotics are indicated.

References:

1.Semler MW, Janz DR, Lentz RJ, et al. Randomized Trial of Apneic Oxygenation during Endotracheal Intubation of the Critically Ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015:rccm.201507–1294OC.

2. Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I et al. Executive Summary: IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis in Children and Adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 54(8):1041-1045. 2012

3. “Ten Things Physicians and Patients Should Question.” American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Released April 4, 2012

4. “Treating Sinusitis.” Choosing Wisely. April 2012.

5. Sharp AL, Klau MH, Keschner JD et al. “Low-Value Care for Acute Sinusitis Encounters: Who’s Choosing Wisely?” Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(7):479-485