We cover ultrasound guided pericardiocentesis using the posts from EMin5, CoreEM, and the Ultrasound Podcast.

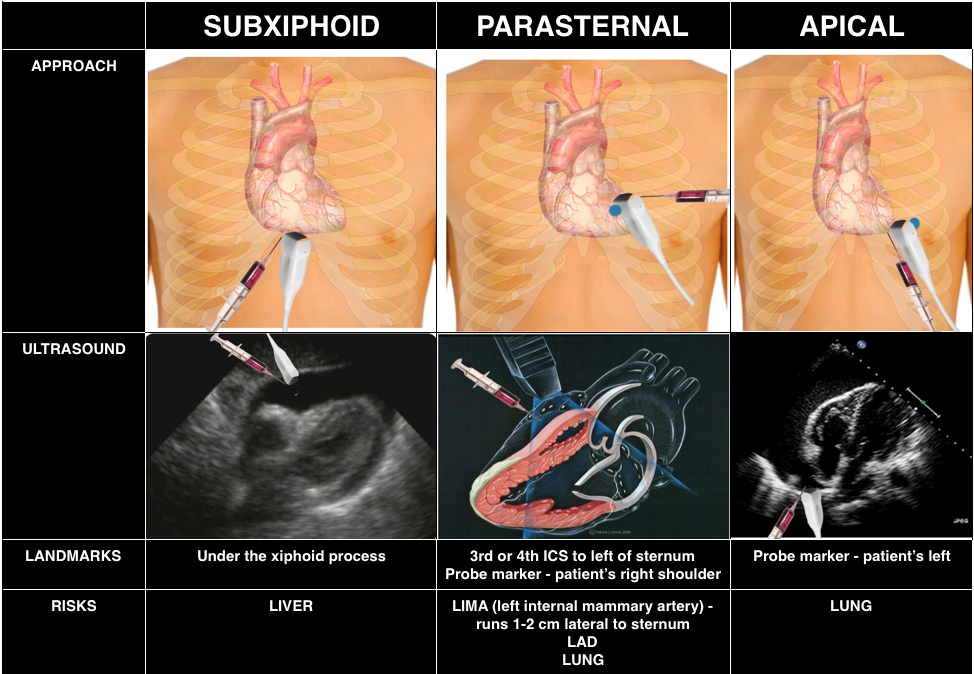

Historically, pericardiocentesis is taught using a landmark based method; however, use of ultrasound guidance may increase success. Experts recommend an approach wherever the largest pocket of fluid exists and each location has particular downsides to be aware of.

Core Content

We delve into core content on the pericardium using Rosen’s (8th ed) Chapter 82 and Tintinalli (8th ed) Chapter 55.

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

1.A 25-year-old man presents to the ED with chest pain, shortness of breath, and fever. Vital signs include BP 98/50 mm Hg, HR 136 beats/minute, RR 26 breaths/minute, and T 102.4°F. On auscultation, you hear rales to the mid-thorax bilaterally. Bedside cardiac ultrasound shows global hypokinesis and a small pericardial effusion. Which of the following organisms is the most common cause of this condition worldwide?

A. Coxsackievirus B

B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis

C. Plasmodium falciparum

D. Trypanosoma cruzi

- [accordion]

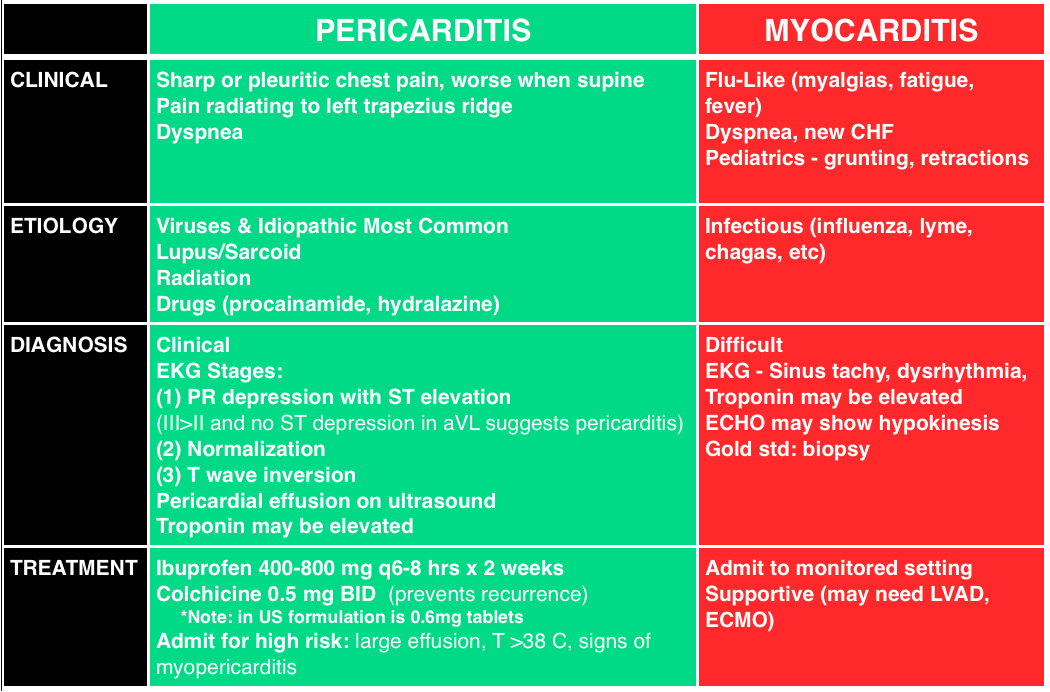

[toggle title=”Answers” state=”closed”]D. Trypanosoma cruz. This patient presents with signs and symptoms of myocarditis accompanied by pericarditis. Myocardial injury results from inflammation of the myocardium. The most common etiology worldwide is Chagas disease, caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. The protozoan is spread by the reduviid bug, also known as the kissing bug as it feeds on the faces of those affected. Unfortunately, in many patients, the cause of myocarditis is idiopathic. Other noninfectious causes include connective tissue disorders such as scleroderma, toxins such as chemotherapy, cocaine, and heavy metals, and peripartum myocarditis. Symptoms often include a viral prodrome with fever, myalgias, and generalized weakness. Patients may present with chest pain, symptoms of acute heart failure, tachycardia, dysrhythmias, syncope, cardiogenic shock, or even sudden cardiac death. Diagnosis can be very difficult and patients often present to the ED multiple times prior to being diagnosed. An ECG may show global or segmental ST elevation, nonspecific ST segment and T wave changes, dysrhythmias, or conduction delays. Troponin and creatinine phosphokinase are often elevated. Echocardiography classically shows global hypokinesis. Management is primarily supportive; however, patients with new left bundle branch block or low ejection fraction may require a left ventricular assist device as a bridge to cardiac transplantation in some cases as these are poor prognostic indicators. The most common long-term sequelae of myocarditis is dilated cardiomyopathy.[/toggle]

[/accordion]

2.A 56-year-old woman with a history of lymphoma presents to the Emergency Department at the recommendation of her primary care physician. During a routine visit, she had a chest X-ray that showed a “big heart.” She denies chest pain, shortness of breath, leg swelling, cough, orthopnea, or lightheadedness. Her vital signs include temperature 98.6 ºF, HR 88 beats/minute and regular, RR 14 breaths/minute, BP 121/89 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. Her cardiac and neck exams are within normal limits. A bedside ultrasound reveals a small pericardial effusion. Which of the following is the next best step in management?

A.Lower extremity ultrasound

B. Pericardiocentesis

C. Reassurance and close follow up

D. Thoracic Surgery consultation

- [accordion]

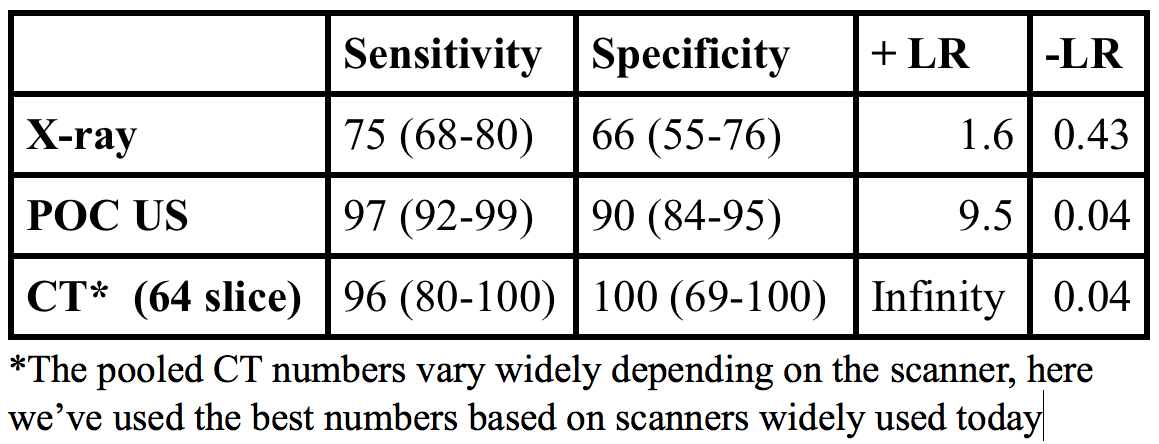

[toggle title=”Answers” state=”closed”] C. Reassurance and close follow up. The patient likely has a malignant pericardial effusion secondary to her known malignancy. Pericardial effusions are accumulations of fluid in the pericardial space that occur rapidly or gradually. Rapid accumulation of pericardial effusion can produce tamponade physiology and hypotension. This requires pericardiocentesis for emergent decompression of the effusion. Pericardial effusions that develop gradually often occur secondary to cancer (e.g. lymphoma, lung cancer, breast cancer, melanoma) or as the result of cancer treatment (e.g. radiation). Clinical signs or symptoms are determined by the rate of fluid accumulation. Asymptomatic pericardial effusions require no immediate treatment. Echocardiography is the diagnostic tool of choice. Chest X-ray may show a large cardiac silhouette indicating gradual fluid accumulation within a stretched pericardium. Malignant pericardial effusions can be managed in a variety of ways, including systemic or intrapericardial chemotherapy, or a pericardial window with pericardial resection. Lower extremity venous ultrasound (A) is an imaging modality to evaluating and diagnosing a deep venous thrombosis (DVT). This patient has no clinical features suggesting a DVT. Pericardiocentesis (B) is indicated in patients with symptomatic pericardial effusions or those who are experiencing tamponade physiology with hypotension. Thoracic surgery consultation (D) is not indicated since the patient is asymptomatic and hemodynamically stable.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

3. A 4-year-old girl is brought to the ER by her parents due to lethargy. A week prior the girl had a cough and colds. Later symptoms progressed to include fever and malaise. She has been less active with decreased appetite. A few hours prior to arrival in the ER, she has been having difficulty of breathing. On exam, temperature is 38.3°C, respiratory rate of 35, heart rate of 126, blood pressure of 90/60, clear breath sounds, hepatomegaly, and poor pulses. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Bronchiolitis

B. Dysrhythmia

C. Myocarditis

D. Pneumonia

- [accordion]

[toggle title=”Answers” state=”closed”]The girl demonstrates signs and symptoms that are suspicious for myocarditis which is a condition that results from inflammation of the heart muscle. Majority of children present with acute or fulminant disease. Myocarditis can be caused by infectious, toxic, or autoimmune conditions. Common causes of viral myocarditis include enterovirus (coxsackie group B), adenovirus, parvovirus B19, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human herpes 6 (HHV-6). The presentation of the disease is variable and patients can present with broad symptoms that range from subclinical disease to cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, and sudden death. There is usually a history of a recent respiratory or gastrointestinal illness within the previous weeks. There is a prodrome of fever, myalgia, and malaise several days prior to the onset of symptoms of heart dysfunction. Then patients present with heart failure symptoms that include dyspnea at rest, exercise intolerance, syncope, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hepatomegaly. Testing is focused on determining the severity of cardiac dysfunction and these include electrocardiography (ECG), cardiac biomarkers, chest radiography, and echocardiography. Confirmation of myocarditis is generally made by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or endomyocardial biopsy.

Dysrhythmia (B) usually presents with palpitations, syncope, chest pain. In the vignette, the girl’s symptoms are more consistent with a myocarditis. A primary dysrhythmia resulting in myocardial injury is differentiated from myocarditis by an endomyocardial biopsy. Bronchiolitis (A) is typically a disease in children younger than two years of age. It is diagnosed clinically with the characteristic findings of a viral upper respiratory prodrome followed by increased respiratory effort. Pneumonia (D) usually presents with respiratory complaints, particularly cough, tachypnea, retractions, and abnormal lung examination which were not present in the vignette.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]