(ITUNES OR Listen Here)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

Jane Brody wrote an article, “What Comes After the Heimlich Maneuver” that ran in the NY Times and stirred up a ruckus on Twitter. This is a reasonable article on choking and details the limitations of the Heimlich maneuver. Unfortunately, the article ends instructing the layperson do to a cricothyrotomy (cric) with a sharp knife and “something like a straw or casing of a ballpoint pen (first remove the ink cartridge). “

Dr. Seth Trueger (@MDaware) wrote a post, Bad Idea Jeans, discouraging this practice saying that deciding which patient needs a cric is one of the more difficult but more important parts of this procedure.

On another note, our friend Dr. Andy Neill has found that medical students are able to perform crics with Papermate pens on cadavers [1]. However, it appears that most pens may not be suitable [2]. Further, while medical students are nearly lay people, we do not think this the cric should be within the domain of lay people (especially without patients already declared dead and preserved).

Cricothyrotomies – In reality, this is a bloody procedures that should only be done by those with proper training when the airway cannot be otherwise secured. The actual procedure has been detailed by those far smarter and with more experience than the FOAMcast crew. We recommend checking out Dr. Scott Weingart’s compilation of resources here.

The anatomy of a cricothyrotomy by Dr. Andy Neill

Core Content – Tracheostomy Emergencies and Neck Infections

Tintinalli (7e) Chapters 242, 119

Tracheostomy (trach) (we refer to tracheostomy and tracheotomy interchangeably although there are some technical differences)

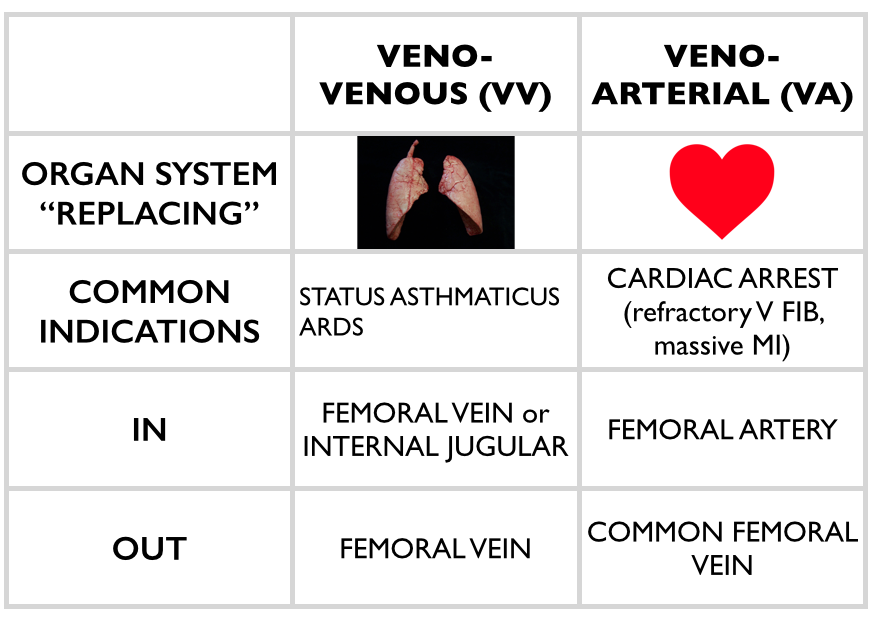

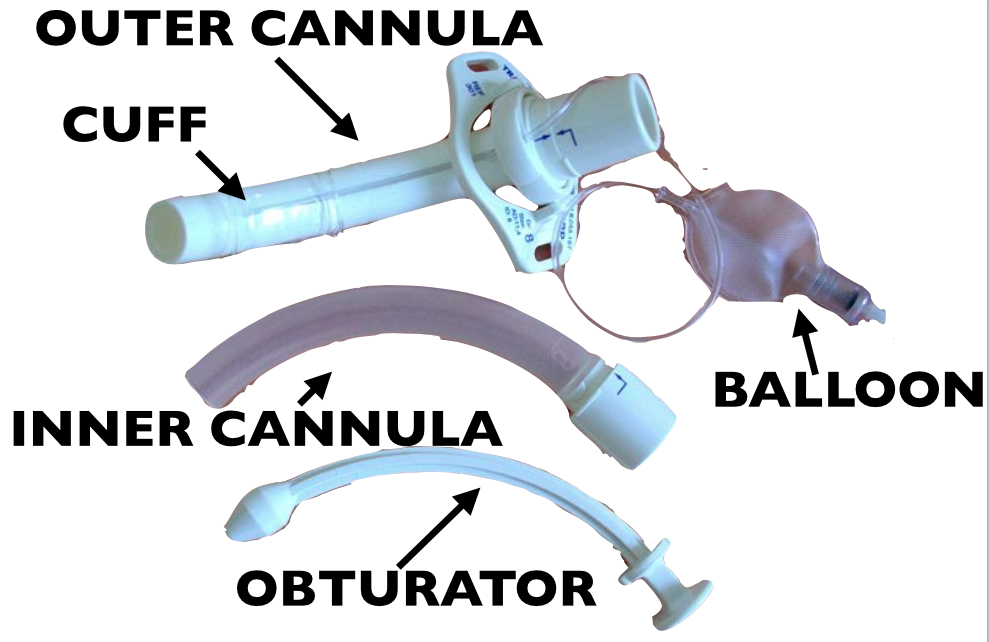

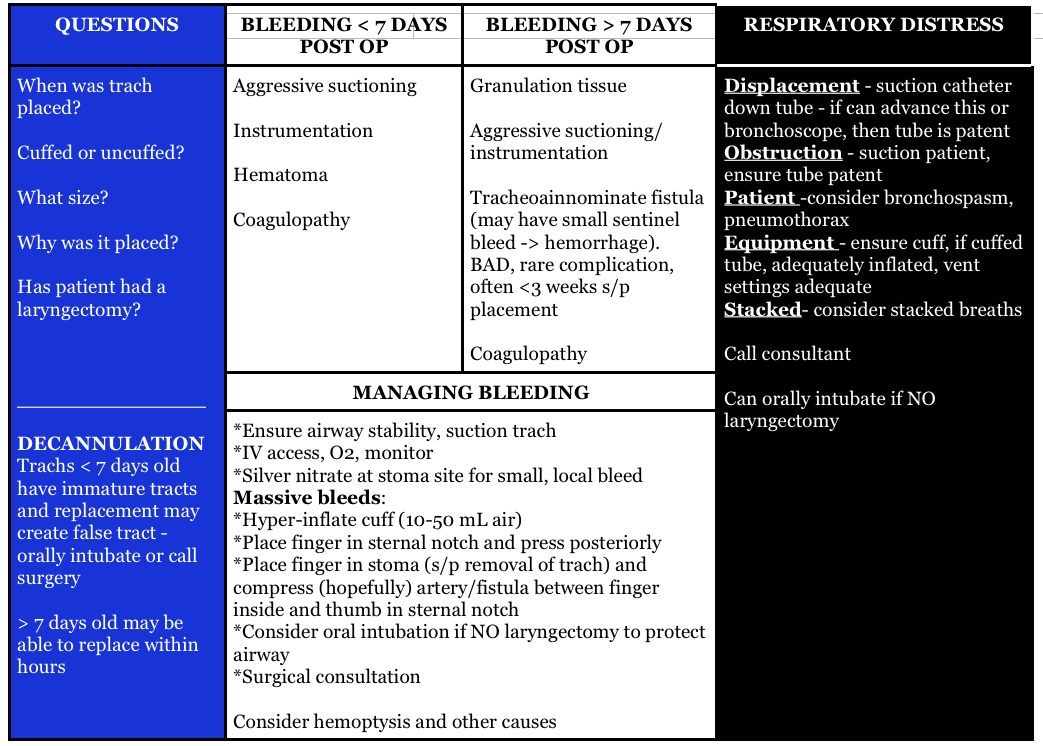

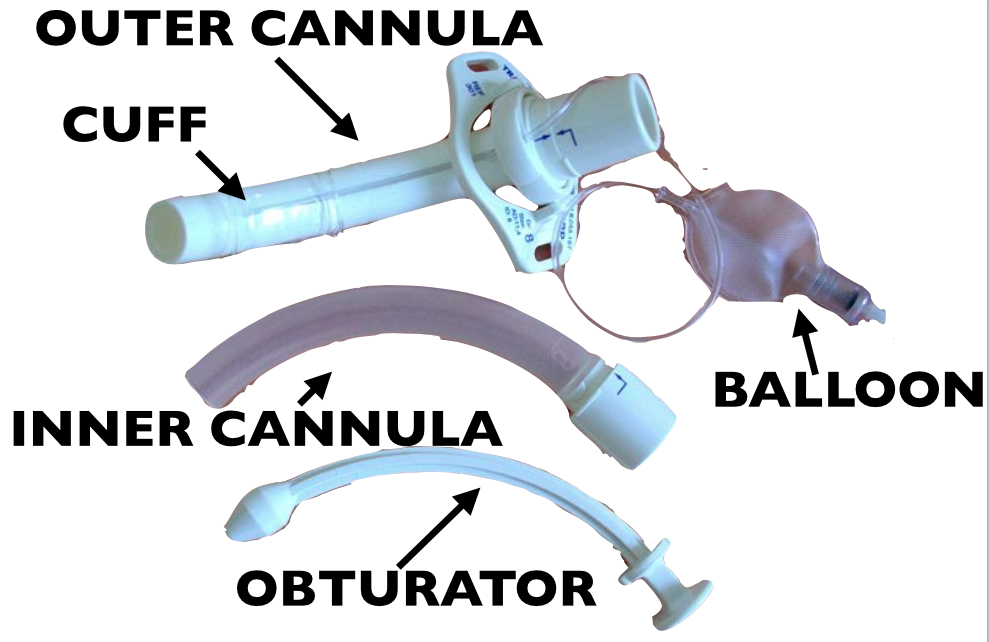

Anatomy of the trach tube (may vary)

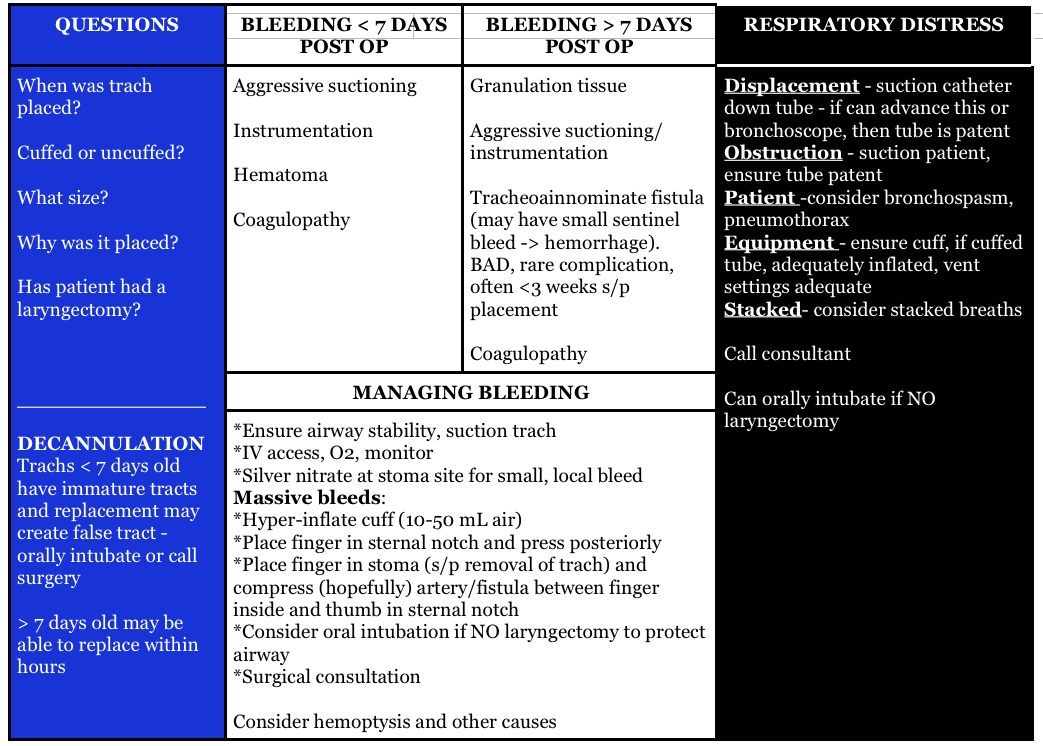

Things we have to know about trach emergencies

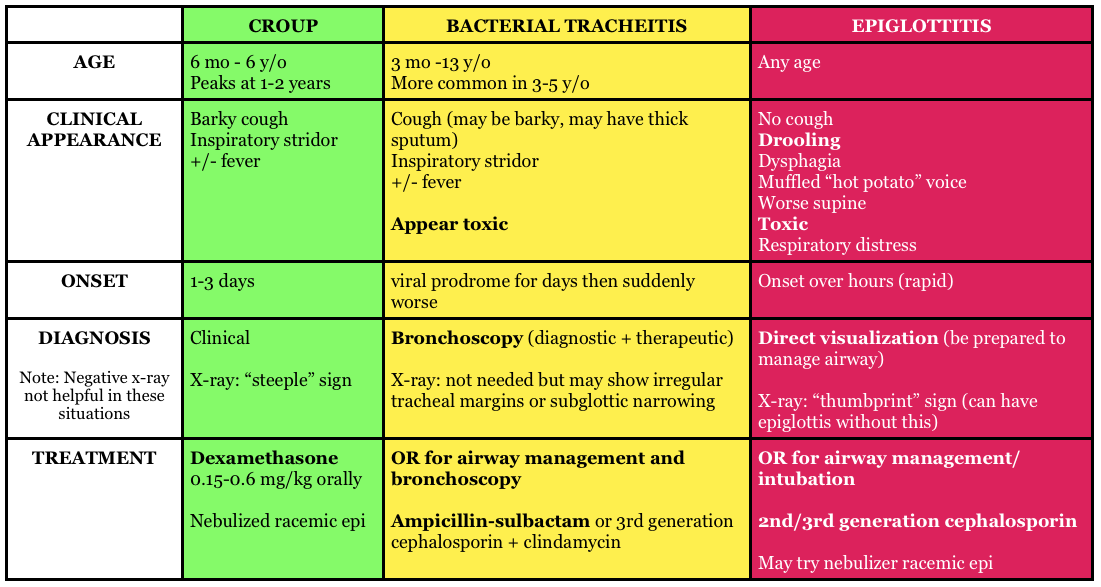

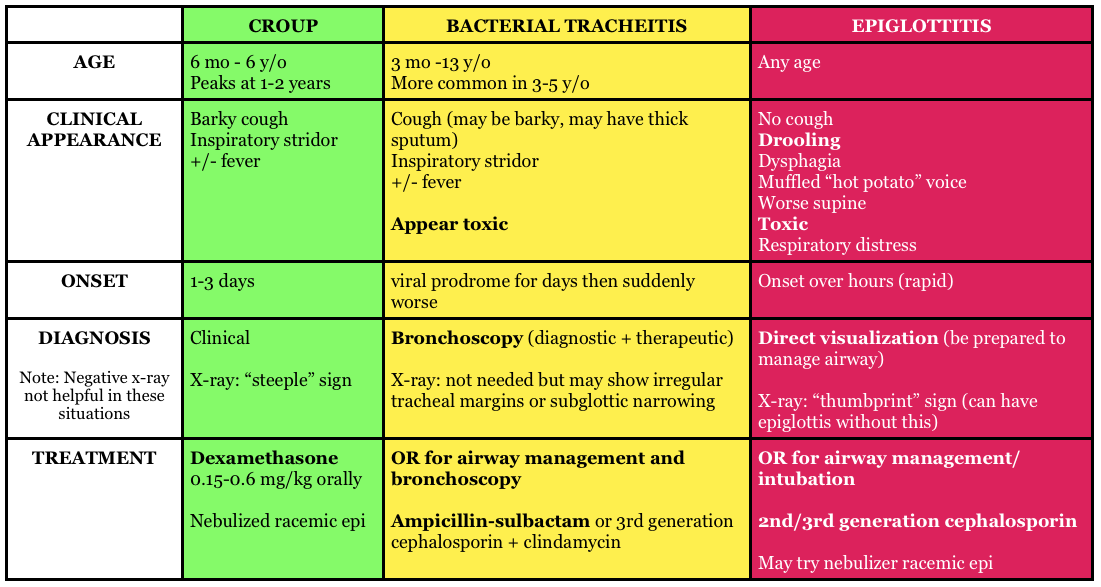

Pediatric Trachea (Stridor) Pearls

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. A 72-year-old man who is 1 week out from an ischemic stroke presents with respiratory distress. He had a tracheostomy placed 6 days ago for sudden respiratory failure. The patient is hypoxic and tachypneic on presentation with minimal breath sounds bilaterally. There is no subcutaneous air around the stoma.[polldaddy poll=9110296]

Question 2. A 3-year-old boy presents in severe respiratory distress. His mother informs you that he has been ill for the last 5 days, initially with a low-grade fever and “barky cough.” He was seen at an urgent care facility 4 days ago and given a “breathing treatment” and discharged on steroids. He has become progressively worse despite compliance with the steroid regimen, which prompted his mother to call an ambulance this morning. He is otherwise healthy and up-to-date on his immunizations. On examination, the child is toxic in appearance and febrile. His oropharynx is clear. You hear both inspiratory and expiratory stridor. [polldaddy poll=9110301]

Answers

1.The patient’s presentation is concerning for airway obstruction and the first step in management is suctioning of the tracheostomy tube. Tracheostomy tubes are placed for long-term mechanical ventilation in patients with anticipated prolonged or permanent respiratory failure. The two most common complications are obstruction and dislodgement. Sudden onset of respiratory failure often indicates mucous plugging or equipment failure. Suctioning of the tracheostomy is a simple procedure that may quickly relieve the patient’s symptoms. 2 to 3 ml of normal saline should be instilled into the tube followed by suctioning. Patients with slower decline in respiratory status may have a worsening of their underlying pulmonary pathology or may have developed a pulmonary infection. A cricothyrotomy (A) will not lead to effective oxygenation or ventilation as the cricothyroid membrane is above the tracheostomy site. The tracheostomy tube should not be removed and replaced with either an endotracheal tube (C) or a new tracheostomy tube (B) at this time because the tracheostomy tract has not matured at 6 days (this usually occurs at 15-30 days). If equipment failure in the form of a tracheostomy tube malfunction is suspected, the tube should be replaced with fiberoptic visualization to ensure that a false lumen isn’t created.

2.The patient is suffering from acute bacterial tracheitis. Bacterial tracheitis is the result of severe inflammation of the epithelial lining of the trachea leading to thick mucopurulent secretion production. This clinically manifests as viral prodrome with fever, URI symptoms, barky cough and stridor that intensifies and progresses to include a toxic appearing child with signs of airway obstruction, inspiratory and expiratory stridor, cyanosis, and severe respiratory distress. Another clue is that the child has been treated with medications (aerosolized epinephrine and steroids) for croup and has not improved clinically. Bacterial tracheitis is most common in children between the ages of 3 to 5 years. Most patients require orotracheal intubation for respiratory distress and ICU admission. The patient should be started on broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. Croup (B) is the most common cause of upper airway distress and obstruction in children between 6 months to 6 years of age with peak incidence at 2 years of age. Croup begins as a prodrome of low-grade fever and URI symptoms and is characterized by a barky cough, inspiratory stridor, and hoarse voice. Children are less toxic in appearance and rarely develop respiratory failure. The mainstays of treatment are steroids and aerosolized epinephrine. Epiglottitis (C) is characterized by abrupt onset of fever and sore throat and children classically present with difficulty in breathing, anxiety, stridor and drooling. This is less common in vaccinated children, such as the patient above and typically occurs in slightly older children. There is generally not a prodrome associated with epiglottitis. Peritonsillar abscess (D) occurs more commonly during adolescence and presents with trismus, unilateral sore throat, fever, tonsillar asymmetry, and uvula deviation away from the affected tonsil. The age of this patient and normal oropharynx examination make this diagnosis very unlikely.

References:

- Neill A, Anderson P. Observational cadaveric study of emergency bystander cricothyroidotomy with a ballpoint pen by untrained junior doctors and medical students. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 30(4):308-11. 2013. [pubmed]

- Owens D, Greenwood B, Galley A, Tomkinson A, Woolley S. Airflow efficacy of ballpoint pen tubes: a consideration for use in bystander cricothyrotomy. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 27(4):317-20. 2010. [pubmed]