(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

We cover one of Dr. Ken Milne’s podcasts on The Skeptic’s Guide to Emergency Medicine on regional anesthesia for hip fractures. They cover a systematic review by Ritcey et al that found a reduction in pain scores in adult patients with femoral neck or hip fractures receiving one of the following means of regional anesthesia:

- Femoral Nerve Block (Review from UltrasoundPodcast)

- 3-in-1 Femoral Nerve Block

- Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block

Why may this be important?

- Better pain control for uncomfortable patients. Many patients with hip and femoral neck fractures are elderly. As such, opioids may be underdosed or pain medications may be used sparingly in these patients. Further, patients may still have pain with transfers.

- Reduction in opioids. Opioids relieve pain but often have deleterious side effects. In addition to hypotension and allergic reactions, opioids may cause delirium.

Why don’t we do it? As a knowledge translation project, Dr. Milne’s podcast aims to propagate the best available, clinically relevant information to practitioners to mitigate the knowledge translation gap as much of the other world provides these blocks routinely to suspected fractures. A study by Haslam and colleagues from Canada suggests that while emergency providers know regional anesthesia is good in this scenario there are other barriers to adoption in North America [2]. Systemic barriers exist and include consultant worries about compartment syndrome, which is largely unfounded [3]. See this post for a more in-depth exploration.

Core Content

Compartment Syndrome – Tintinalli (7e) Chapter 275, “Compartment Syndrome.” Rosen’s (8e) Chapter 49, “General Principles of Orthopedic Injuries.”

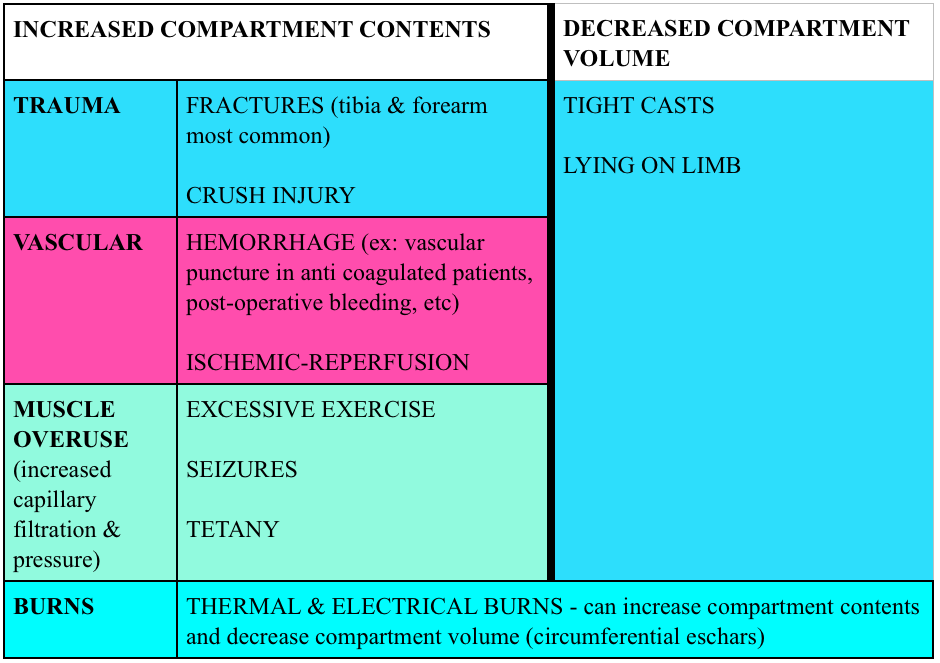

Compartment syndrome is typically caused by too much pressure in a confined space. Compartments are often surrounded by fascia and tissue with limited ability to stretch. When the volume in the compartment increases or external forces compresses the compartment, blood flow in and out of the compartment are compromised. Certain areas of the body are more predisposed to compartment syndrome (classics are the lower leg in tibia fractures and the forearm compartments).

Causes: Most cases of compartment syndrome are caused by fractures (~75%) but certainly not all.

Diagnosis:

- Clinical. Classically this was taught as the 5 P’s (pain, parethesias, pallor, pulselessness, poikilothermia). Yet, many of these perform poorly in real life.

- Compartment pressures. Many commercial devices exist to measure compartment pressures, yet these readings have poor specificity for compartment syndrome.

- Historically, compartment pressures >30 mmHg or a delta pressure (Diastolic pressure minus the compartment pressure) <20-30 mmHg has indicated compartment syndrome.

- Studies have measured compartment pressures on long bone fracture patients NOT suspected of having compartment syndrome and found that acting based on pressures would have resulted in 24-35% overdiagnosis (depending on a delta pressure cut-off of 20 mmHg and 30 mmHg respectively) [4-5]

Treatment:

- Fasciotomy. Suspect compartment syndrome? Call surgery. In the the meantime, remove constrictive bands or clothing, give analgesia, place the limb in a dependent position, assess for rhabdomyolysis.

More FOAM on compartment syndrome: CoreEM

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

1. A 24-year-old long distance athlete was brought to the emergency room complaining of severe leg pain in his left anterior lower leg. The pain became worse while running his ultra marathon yesterday and subsided after he finished. However he went for a run today and the pain returned. He describes the pain as a burning, tight pain that is 10/10. On physical exam he is in exquisite discomfort. There are no signs of trauma or broken bones. The pain is worsened on passive stretching of the leg. On palpation of his legs there is a firm wooden feeling. Distal pulses are palpated however his left leg does appear very pale. He has diminished 2-point sensory discrimination in his left leg compared to his right leg. [polldaddy poll=9241018]

2. You obtain a radiograph of a patient who was in a MVC. His GCS is 15. While being observed in the ED, the patient requests increasing doses of pain medication and is complaining of a deep, burning, unrelenting pain to his left lower extremity. He also states that he now feels tingling in his calf. [polldaddy poll=9241033]

Answers.

- Compartment syndrome is a serious emergency complication that should be considered whenever pain and paresthesias occur in an extremity after a fracture within an enclosed osseofascial space. It is caused by increased pressure within the compartment space that prevents adequate tissue perfusion. Compartment syndrome is most commonly associated with closed long-bone fractures of the tibia, but it can occur with isolated soft tissue trauma and even in open fractures. It has been described in a variety of situations such as prolonged procedures in the lithotomy position, the tuck position (knees tucked to chest for lumbar surgery), bedridden patients, from a spontaneous hemorrhage, and even the application of excessive traction in the reduction of a fracture. Compression dressings (A) and external wrappings should be avoided; increased compression will worsen perfusion. Elevating the limb (B) results in reduction in the local arteriovenous gradient and may be counterproductive and exacerbate compartment syndrome. It is best to keep the extremity level or slightly elevated (<10 degrees). Pressures <30 mmg Hg (C) generally do not produce compartment syndrome. The best measure of adequate limb perfusion, however, is not absolute compartment pressure but rather the differential between diastolic blood pressure and absolute compartment pressure. A pressure differential <30 mm Hg is considered by most to be an indication for emergent fasciotomy. However, with strong clinical suspicion, a fasciotomy may be required at any pressure differential as this is largely a clinical diagnosis. The initial presentation of compartment syndrome (E) usually begins with pain with passive stretching of the muscle groups, paresthesias with decreased sensation, and pain that is out of proportion to exam. Pallor and the loss of pulses are late and ominous findings.

- Compartment syndrome is a serious emergency complication that should be considered whenever pain and paresthesias occur in an extremity after a fracture within an enclosed osseofascial space. It is caused by increased pressure within the compartment space that prevents adequate tissue perfusion. Compartment syndrome is most commonly associated with closed long-bone fractures of the tibia, but it can occur with isolated soft tissue trauma and even in open fractures. It has been described in a variety of situations such as prolonged procedures in the lithotomy position, the tuck position (knees tucked to chest for lumbar surgery), bedridden patients, from a spontaneous hemorrhage, and even the application of excessive traction in the reduction of a fracture. Compression dressings (A) and external wrappings should be avoided; increased compression will worsen perfusion. Elevating the limb (B) results in reduction in the local arteriovenous gradient and may be counterproductive and exacerbate compartment syndrome. It is best to keep the extremity level or slightly elevated (<10 degrees). Pressures <30 mmg Hg (C) generally do not produce compartment syndrome. The best measure of adequate limb perfusion, however, is not absolute compartment pressure but rather the differential between diastolic blood pressure and absolute compartment pressure. A pressure differential <30 mm Hg is considered by most to be an indication for emergent fasciotomy. However, with strong clinical suspicion, a fasciotomy may be required at any pressure differential as this is largely a clinical diagnosis. The initial presentation of compartment syndrome (E) usually begins with pain with passive stretching of the muscle groups, paresthesias with decreased sensation, and pain that is out of proportion to exam. Pallor and the loss of pulses are late and ominous findings.

References:

- “Hip and Femur Injuries.” Chapter 270. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide.

- Haslam L, Lansdown A, Lee J, et al. Survey of Current Practices: Peripheral Nerve Block Utilization by ED Physicians for Treatment of Pain in the Hip Fracture Patient Population. Canadian geriatrics journal : CGJ. 2013;16(1):16–21.

- Karagiannis G, Hardern R. Best evidence topic report. No evidence found that a femoral nerve block in cases of femoral shaft fractures can delay the diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the thigh. Emerg Med J. 2005 Nov;22(11):814.Bhalla MC, Dick-Perez R. Exercise Induced Rhabdomyolysis with Compartment Syndrome and Renal Failure. Case Reports in Emergency Medicine. 2014:1-3. 2014.

- Whitney A, O’Toole RV, Hui E. Do one-time intracompartmental pressure measurements have a high false-positive rate in diagnosing compartment syndrome? The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 76(2):479-83. 2014.

- Nelson JA. Compartment pressure measurements have poor specificity for compartment syndrome in the traumatized limb. The Journal of emergency medicine. 44(5):1039-44. 2013.

thanks guys for this timely episode. ON twitter yesterday we had a discussion on this in regard to fears of missing compartment syndrome if using regional nerve blocks for limb injuries.

I have been using nerve blocks more since adopting prehospital ultrasound in the field and it is vastly superior to our traditional approach of systemic analgesia for isolated limb injuries.

It is far easier to adequately assess the limb for compartment syndrome if the leg is anaesthetised. You can do your pressure measures and monitoring without cruelty.

The literature has explored this issue as you mention and concluded there is little need to fear using regional blocks in limb injuries. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22561421

http://www.scitechnol.com/compartment-syndrome-risk-a-contraindication-to-regional-analgesia-W9bh.php?article_id=252

http://bja.oxfordjournals.org/content/102/1/3.short

Ultimately I regard this pervasive fear to be akin to the old surgical dogma of withholding analgesia in acute abdominal pain to avoid masking clinical signs.

Hey guys, I’m a first time listener and I love what you’re doing so keep it up! Just wanted to say thanks for the attention you’re drawing to our study, which I think is important for us to discuss as emergency physicians to get others on board with this great intervention that really makes a difference for patients.

We did this study because we wanted to draw attention to nerve blocks, which are nothing new in medicine, but have been severely under-utilized in the ED for a number of reasons. We had to fight many battles to get people on board at our institution because of the fear from orthopedics about missing compartment syndrome and the theoretical risk of falls, and the fear from anesthesia that we were going to be poisoning our patients with local anesthetic toxicity and causing permanent injury by blowing up their femoral nerve with an intraneural injection, but we’re finally getting to the point now that people are starting to see the benefits. We wanted to look for complications such as compartment syndrome, local anesthetic toxicity, delirium and more in this study but unfortunately just found the outcome reporting was garbage in most of the studies and we just threw out all the data we collected because it just wasn’t valid. It’s worth mentioning that we didn’t find ANY instances of compartment syndrome, nerve injury, or local anesthetic toxicity which likely would have been reported if they happened because they’re fairly dramatic events, but we need better structured studies like the article by Beaudoin et al (Acad Emerg Med 2013) to really answer the question about complications.

I think when it comes to hip and femur fractures, Minh hits the nail on the head by saying that nerve blocks improve your clinical assessment for compartment syndrome, rather than hinder it. When you have good analgesia it’s extremely easy to reduce significantly displaced mid-femur fractures and check compartment pressures. Plus, when it comes to hip fractures it’s incredibly unlikely to get a compartment syndrome at all, and since for hip fractures the femoral head has innervation from other nerves as well they will have breakthrough pain if they have elevated compartment pressures, even if you’ve blocked the femoral nerve.

The one other thing I’d add to what you said in the podcast was that while bupivicaine was the most commonly used local anesthetic in the studies we looked at (bupivicaine 0.5% 20-30cc in most), if you have access to ropivicaine at your institution that’s really the ideal local anesthetic for femoral nerve blocks. It has a similar profile in terms of length of action, but has a more forgiving maximum dose (3mg/kg vs 2 mg/kg) which increases the safety of the block. We usually use ropivicaine 0.5% 20 cc for our blocks, and it works for about 14-16 hours.

The one block I really worry about compartment syndrome is the popliteal sciatic block for tibial fractures. I’d love to hear the experience of others out there in the FOAMverse but since tibial fractures can get compartment syndrome just from a dirty look, I prefer to stay away from that one.

Brandon Ritcey

PGY5 Emergency Medicine

University of Ottawa

@DrRitcey

Thanks so much Brandon! Great information. I’ll be sharing this at our conference tomorrow!