We review a podcast from Dr. Tim Horeczko’s Pediatric Emergency Playbook on elbow injuries.

Core Content

We delve into core content on other elbow adjacent injuries using Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) Chapter and Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) Chapter as a guide.

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 63-year-old man presents with left arm pain after a fall. His X-ray is shown below. What structure is commonly injured with this fracture?

A. Axillary nerve

B. Median nerve

C. Radial nerve

D. Ulnar nerve

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

C. Radial nerve injury is the most common nerve injury seen after humeral shaft fractures. These fractures usually occur from a direct blow to the arm and can be seen in falls and motor vehicle collisions. Patients present with severe pain, arm swelling and decreased range of motion. The arm can be shortened or rotated in a complete fracture depending on the location of the fracture. A complete neurovascular exam should be performed as with all fractures and dislocations. The radial nerve may be injured during humeral fracture in up to 20% of patients. The injury is usually a neuropraxia and resolves spontaneously in most patients. However, this recovery can take months. Humeral fractures rarely need specific reduction maneuvers for treatment. They should be placed in a sugar tong splint and placed in a sling. Gravity alone is typically successful in fracture reduction. The axillary nerve (A) may be injured during glenohumeral dislocations. The median nerve (B) may be injured during posterior elbow dislocations. Anterior elbow dislocations can be associated with ulnar nerve injury (D).

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

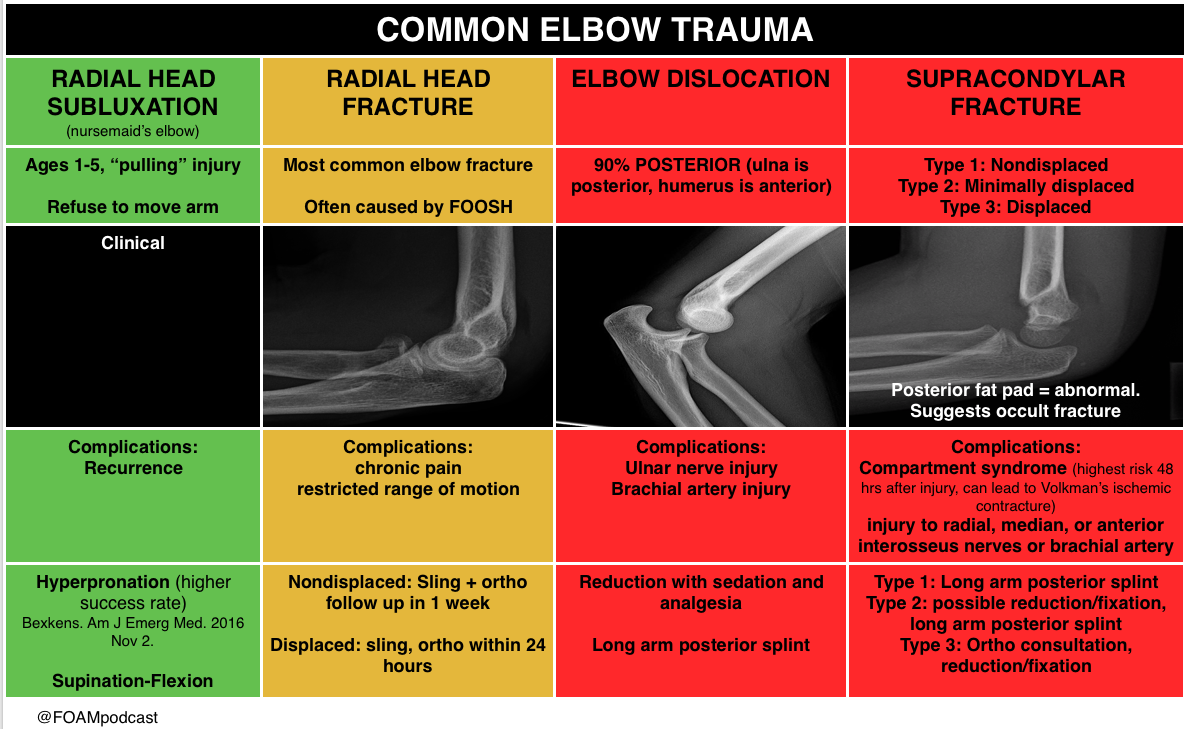

A 3-year-old girl was walking on the sidewalk with her mom when she fell onto the street. In a panicked state, her mom picked up the little girl by her arm. Immediately after, the little girl refused to move her right arm complaining that it hurt. In the emergency room, the girl is holding her right arm in a flexed, pronated, and adducted position. There is no crepitus, swelling or point tenderness along the entire right arm or clavicle. Which of the following is the next step in management of this patient?

A. Actively supinate and flex the elbow while applying pressure over the radial head

B. Consult orthopedics for casting

C. Obtain an ultrasound

D. Perform a skeletal survey

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

A. This child has “nursemaid’s elbow” that is due to subluxation of the annular ligament rather than dislocation of the radial head. The etiology is slippage of the head of the radius under the annular ligament. The distal attachment of the annular ligament covering the radial head is weaker in children than in adults, allowing it to be more easily torn. It occurs in toddlers due to traction via pulling on a pronated and extended arm. The child immediately refuses to the move the arm and often cradles the affected arm. Parents often give a history of a young child with no history of trauma who suddenly refuses to use an arm. The diagnosis is clinical and imaging studies are generally not needed. If reduction is unsuccessful after 2–3 attempts then imaging studies may be warranted. Treatment is manual reduction via supination and flexion or hyperpronation. A palpable click may be felt and the child usually regains immediate movement of the arm and relief of discomfort. A skeletal survey (D) should be obtained in all cases of suspected child abuse to assess for fractures in multiple stages of healing. Child abuse should be on the differential in all pediatric orthopedic cases. Consulting orthopedics for casting (B) is not necessary as this is a dislocation injury. Ultrasonography (C) has been used as a noninvasive modality to assess for annular ligamentous injury and displacement of the radial head from the capitellum. It has also been used to assess progress of treatment for patients with recurrent subluxations, however it is not the first-line diagnostic nor treatment option.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Indomethacin (B) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent commonly used in the treatment of acute gout. Gout is an arthritis caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the joint space. Acute flares involve a monoarticular arthritis with a red, hot, swollen and tender joint. Acute episodes of gout result from overproduction or decreased secretion of uric acid. However, measurement of serum uric acid (C) does not correlate with the presence of absence of an acute flare. A radiograph of the knee (D) may show chronic degenerative changes associated with gout but will not help to differentiate a gouty arthritis versus septic arthritis.

Indomethacin (B) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent commonly used in the treatment of acute gout. Gout is an arthritis caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the joint space. Acute flares involve a monoarticular arthritis with a red, hot, swollen and tender joint. Acute episodes of gout result from overproduction or decreased secretion of uric acid. However, measurement of serum uric acid (C) does not correlate with the presence of absence of an acute flare. A radiograph of the knee (D) may show chronic degenerative changes associated with gout but will not help to differentiate a gouty arthritis versus septic arthritis.