iTunes or Listen Here

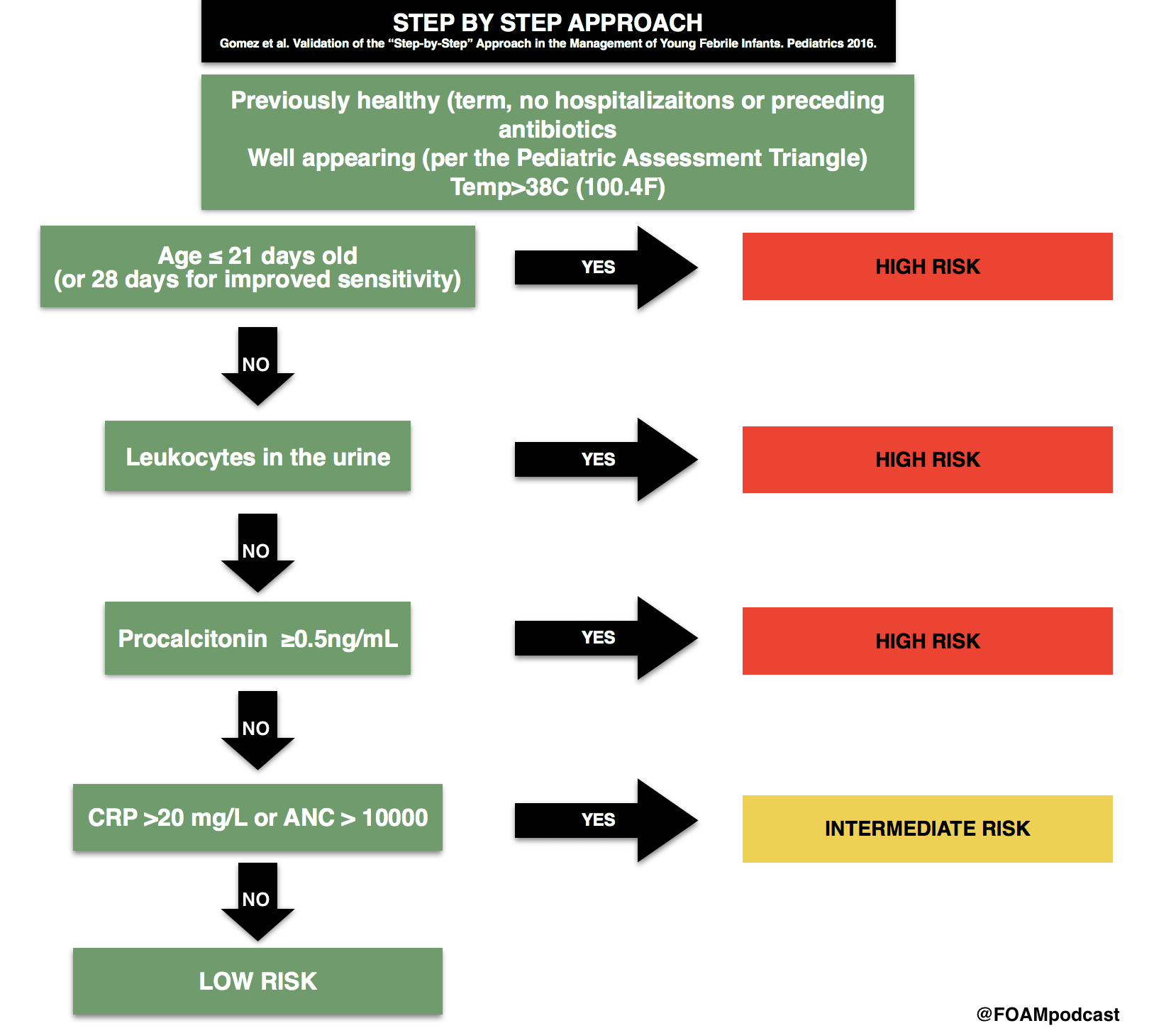

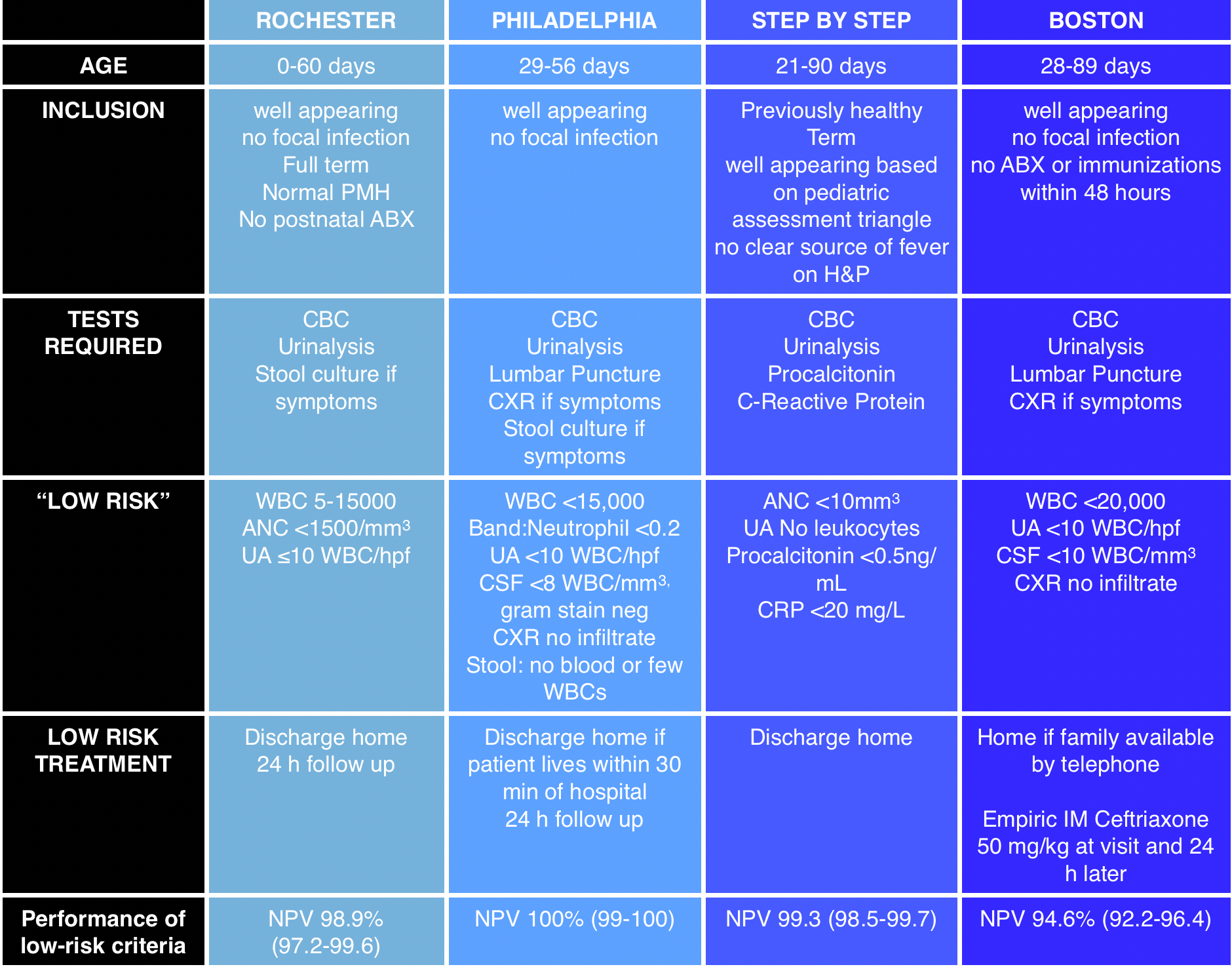

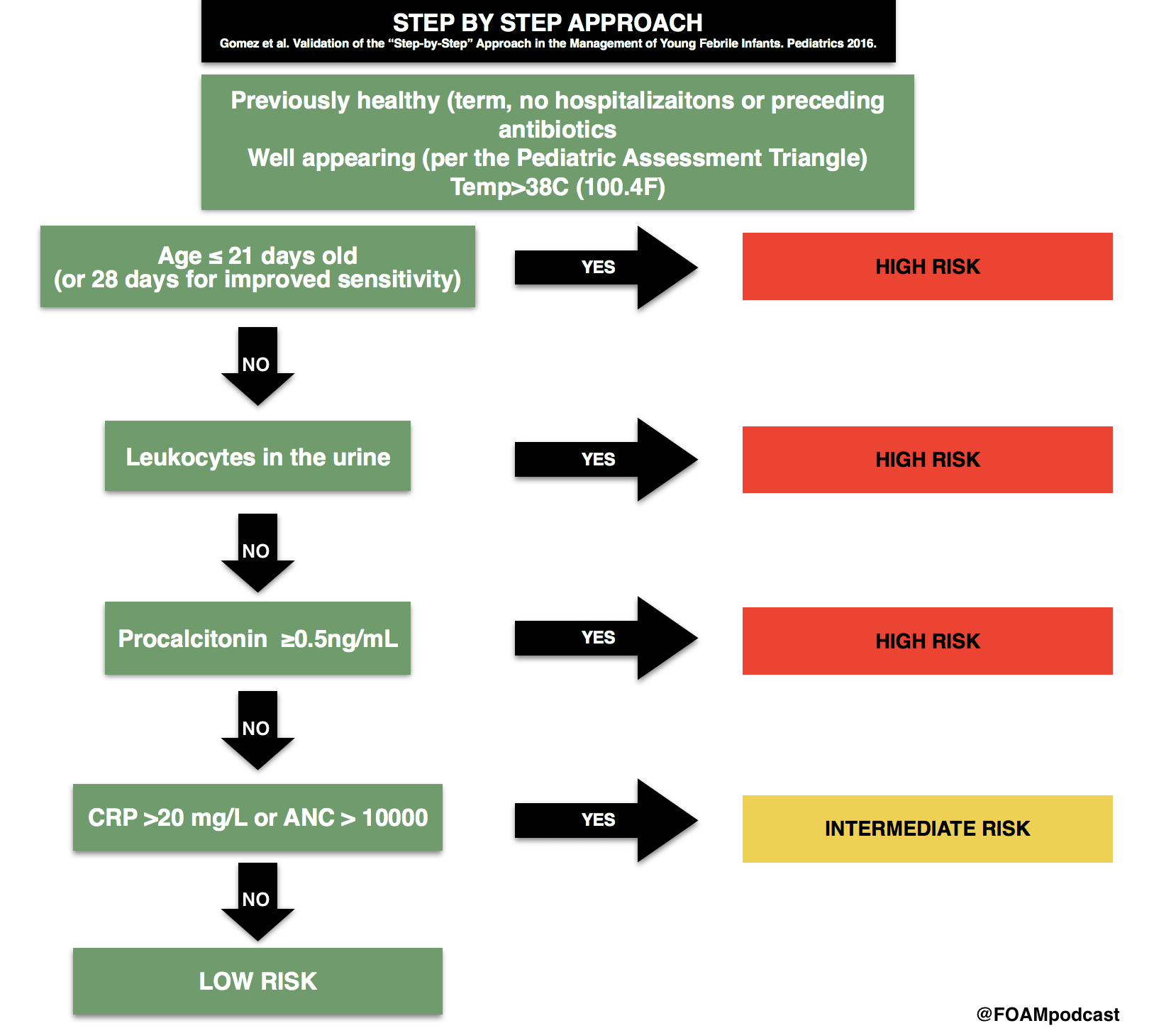

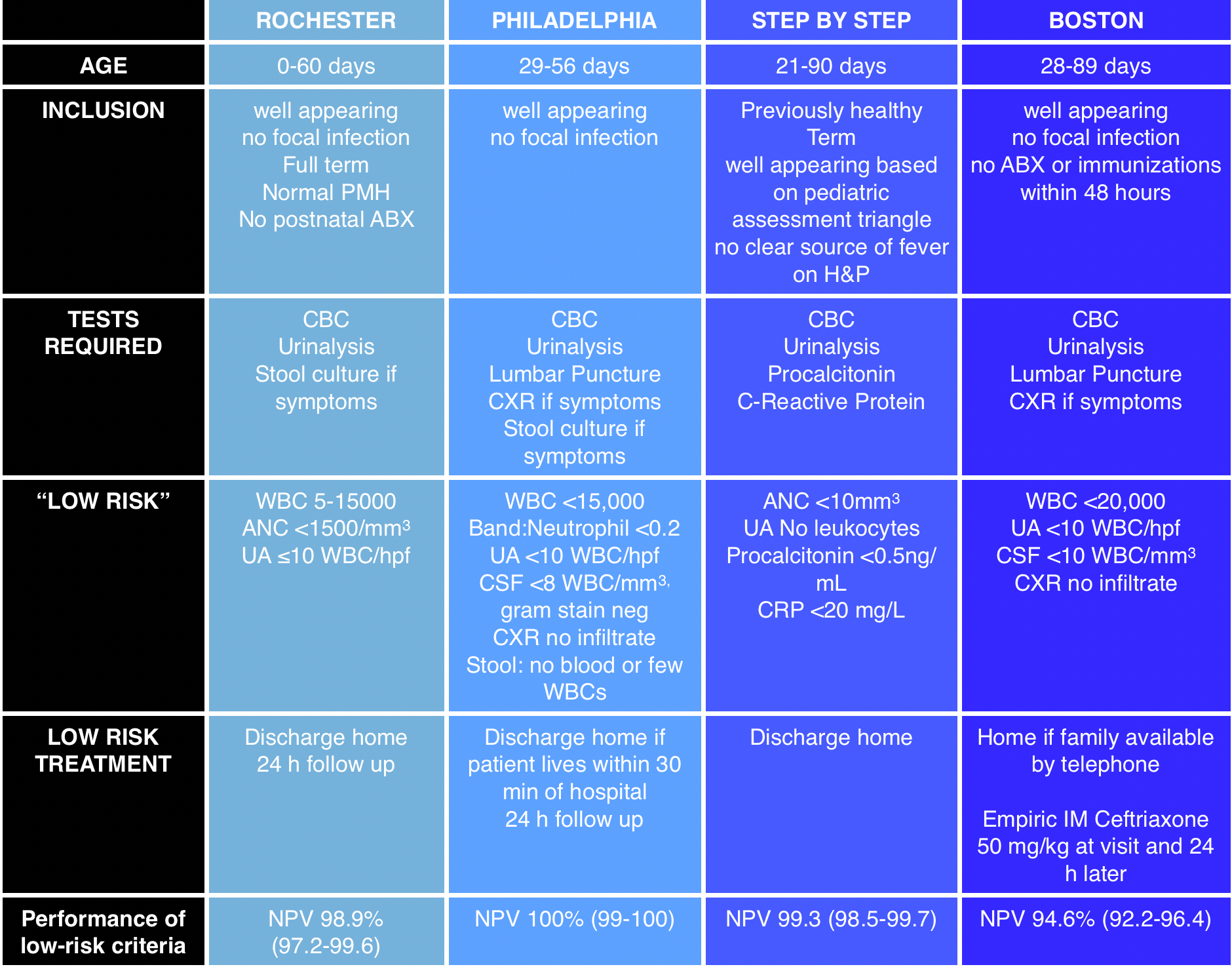

We cover an episode of The Skeptic’s Guide to Emergency Medicine that covers a validation study of the Step by Step approach to pediatric fever. This approach to infants with a fever <3 months old is alluring as it does not necessitate a lumbar puncture. This algorithm had a better sensitivity and negative predictive value than the Rochester criteria. The approach did miss some infants with a serious bacterial infection and these tended to be those between 21 and 28 days old and those with fever onset <2 hours prior to arrival.

Core Content

We cover Chapter 116 in Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine (8th ed) and Rosen’s on pediatric fever.

Infants <3 months old with fever algorithms

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 25-day-old female presents with fever and cough. Mom denies any symptoms at home. The patient’s 2-year-old brother had a cough and rhinorrhea 1 week prior. On exam, the patient’s temperature is 38.7°C with clear lungs, a benign abdomen, and normal tympanic membranes bilaterally. What is the appropriate workup for this patient?

- CBC, chest X-ray

- CBC, chest X-ray, urinalysis

- CBC, chest X-ray, urinalysis, blood cultures

- CBC, chest X-ray, urinalysis, blood cultures, lumbar puncture

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

4. Neonates with fever aged 28 days or younger may have few clues on history and physical examination to guide therapy. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is necessary to detect the febrile neonate with a serious bacterial infection. Obtaining the pertinent medical history from the mother regarding the pregnancy, delivery, and early neonatal life of the febrile neonate is essential. Typically, infections in the 1st week of life are secondary to vertical transmission, and those infections after the 1st week are usually community acquired or hospital acquired. Bacterial meningitis is more common in the 1st month of life than at any other time. An estimated 5%–10% of neonates with early onset group B streptococcal (GBS) sepsis have concurrent meningitis. Therefore, febrile infants (temperature >38°C) younger than 28 days should receive a full sepsis workup. CBC, chest X-ray (A), urinalysis (B), and blood cultures (C) are a partial workup for neonatal fever.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

A two-day-old boy presents to the ED with fever for the past four hours. His birth history includes a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery at term. Parents report noticing that the child “felt warm,” and that he was having copious nasal secretions while feeding. On physical examination, the child appears lethargic, has mottled extremities, and is hot to the touch. Breath sounds are clear bilaterally, and there are no rashes. His vital signs are T 102.9°F, BP 74/48 mm Hg, HR 170 beats per minute, and RR 40 breaths per minute. Which of the following groupings of organisms should your antibiotic choices cover when treating this febrile neonate?

- Listeria monocytogenes, Group B streptococcus, Escherichia coli

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Neisseria meningitidis, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

Answer 1. The febrile neonate is a child 28 days and younger who presents with a fever. These children are at very high risk of serious bacterial infections, including urinary tract infection, pneumonia, meningitis, and bacteremia. Risk factors for serious bacterial infection in a neonate include prematurity, low birth weight, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, meconium aspiration, or maternal group B streptococcus infection. The evaluation of a neonate with a fever includes CBC, urinalysis, blood culture, urine culture, and a lumbar puncture in order to obtain CSF for cell count, Gram stain, and culture. If the child has respiratory symptoms, a chest X-ray should be performed. If the child has diarrhea, stool testing should also be performed. The most common pathogens involved in serious bacterial infections, including meningitis and bacteremia, in neonates are Listeria monocytogenes, Group B streptococcus, and Escherichia coli. These children can become critically ill very rapidly; therefore, initial management should include a fluid bolus of 20 mL/kg and broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover the most common pathogens in this age group. The most appropriate antibiotics to use in neonates with a fever are ampicillin and cefotaxime. Ampicillin will cover Listeria monocytogenes while cefotaxime will cover Group B streptococcus and Escherichia coli. If there is a history of maternal infection with herpes simplex virus, acyclovir should be added to the empiric broad-spectrum treatment. These patients universally need to be admitted to the hospital for IV antibiotics and observation until all cultures have returned. Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae (B) are common pathogens seen in adolescents and young adults. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common cause of atypical pneumonia in this age group. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a common bacterial cause of pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis while Neisseria meningitidis is primarily a cause of meningitis. Neisseria meningitidis, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae (C) are the primary pathogens causing serious bacterial infections in adults over the age of 65. Listeria monocytogenes is a pathogen that is seen in infants and then later reemerges as a prominent pathogen in older adults. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae (D) are the most common pathogens causing serious bacterial infections in children ages one to five years. There has been a significant decline in the incidence of Haemophilus influenzae type B in recent years due to childhood vaccination programs.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]