(ITUNES OR Listen Here)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

We review a post from Dr. Charles Bruen from ResusReview on Malignant Hyperthermia and dantrolene.

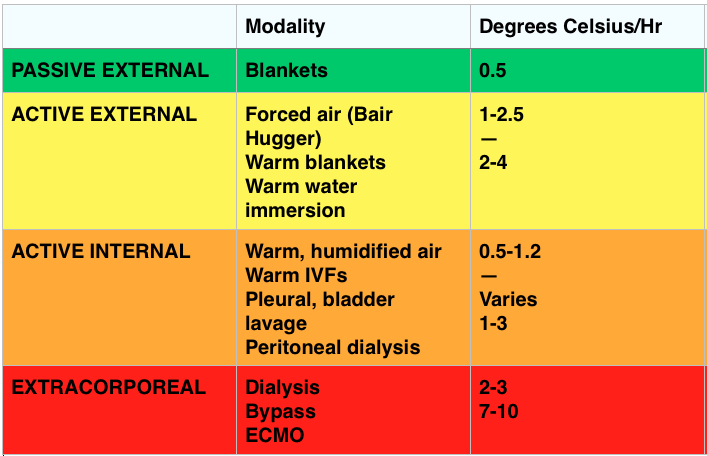

Malignant hyperthermia – a rare condition typically associated with volatile anesthetics, so more often an OR/inpatient issue; however, has been associated with succinylcholine use.

Cause: most often a mutation of the ryanodine receptor which, in the presence of certain anesthetics or succinylcholine causes too much intracellular calcium. This leads to increased ATP production.

Signs/Symptoms: tachycardia, hypercarbia, muscle rigidity, hyperthermia

Treatment – Dantrolene.

- Administer though a large vein

- Caution with calcium channel blockers – may lead to hyperkalemia or myocardial depression

- Dantrolene has also been used in severe dinitrophenol (industrial chemical and weight loss supplement) toxicity – see this Poison Review post.

The Bread and Butter

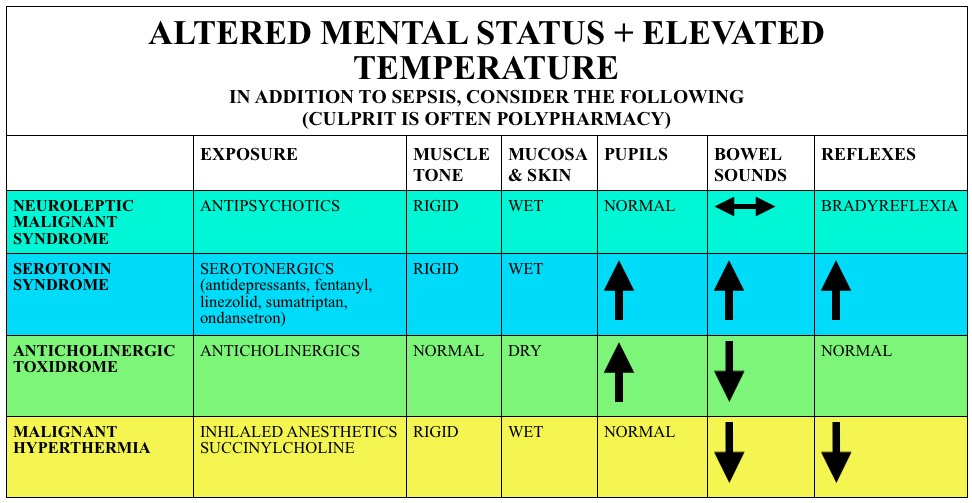

We cover syndromes associated with psychiatric medications and polypharmacy including neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), serotonin syndrome, and some extrapyramidal side effects. We do this based on Rosen’s Emergency and Tintinalli. But, don’t just take our word for it. Go enrich your fundamental understanding yourself.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Caused by atypical antipsychotics, rare, idiosyncratic and may persist for 2+ weeks after discontinuation of the offending medication

Symptoms – Varied diagnostic criteria but requires temp >100.4F + muscle rigidity + at least two of the following (in rough order of frequency):

- Diaphoresis

- Leukocytosis

- AMS

- Elevated creatine kinase

- Labile blood pressure

- Tachycardia

- Tremor

- Incontinence

- Dysphagia

- Mutism

Treatment – remove offending agents, supportive care (intravenous fluids, cooling), benzodiazepines. Dantrolene, amantadine, and bromocriptine are not recommended.

Serotonin Syndrome

(PV card from Academic Life in Emergency Medicine). Caution with the elderly as these symptoms may be attributed to infection or delirium (and vice versa).

Symptoms – Classical clinical triad of AMS + Autonomic instability (Hyperthermia, Tachycardia, diaphoresis) + Neuromuscular Abnormalities: Myoclonus, ocular clonus, rigidity, hyperreflexia, tremor. Yet like most clinical triads, this performs poorly. The Hunter Criteria are often used (Sensitivity ~84%):

- Serotonergic agent plus 1 of the following:

- Spontaneous clonus

- Inducible clonus + agitation or diaphoresis

- Ocular Clonus + agitation or diaphoresis

- Tremor + hyperreflexia

- Hypertonia + temp >38F AND ocular clonus or inducible clonus

Serotonin syndrome often begins with akathisia (restlessness) and body systems become increasingly “ramped up” with tremors, followed by altered mental status, and then incereasing amounts of rigidity (inducible clonus -> Sustained clonus (+/- ocular clonus) -> Muscular rigidity -> Hyperthermia -> Death)

Causes – While often associated with antidepressants, polypharmacy seems to be the culprit here. Serotonin syndrome is commonly associated with some of these medications

- Antidepressants –

- SSRIs/SNRIs – sertraline, fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram, venlafaxine, etc

- Trazodone, Buspirone

- TCAs

- MAOIs

- Analgesics – fentanyl and tramadol

- Antibiotics – Linezolid (Poison Review post)

- Antiemetics – ondansetron, metoclopramide

- Anti-epileptics – depakote

- Anti-tussive – dextromethorphan

- Herbs – St. John’s wort, ginseng

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

Acute Dystonia – involuntary motor tics or muscle spasms classically including torticollis, tongue or lip protrusion, or oculogyric crisis

Akathisia – a feeling of restlessness often accompanied by tapping, pacing, rocking. Reversible.

- ~40% of patients given 10 mg of intravenous prochlorperazine developed akathisia within 1 hour.

Treatment: Benzodiazepines, Benadryl (diphenydramine), Benztropine

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. A 35-year-old man presents with fever, hypertension and altered mental status. He was recently started on haloperidol for schizophrenia. Physical examination reveals a confused patient with muscle rigidity. [polldaddy poll=8842561]

Answers

1. C. FOAMcast editorial: This is an exercise in selecting the *best* answer, not the one that is most correct. You’ve probably noted that a benzodiazepine is not an option, the next best option is dantrolene.

This patient presents with signs and symptoms concerning for neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) and should be treated with dantrolene. NMS is a life-threatening complication of neuroleptic drug treatment. It is rare and only effects 0.5 – 1% of patients receiving these drugs. Although it is more common with use of the typical neuroleptic medications, it can also be seen with the atypical agents. It usually occurs within the first few weeks of starting neuroleptic medications but can also be seen after an increase in dosage. NMS is characterized bymuscle rigidity, fever, altered mental status and autonomic instability. Muscle contraction leads to an elevated serum creatinine kinase. Due to similarities, the disease may be confused with serotonin syndrome. NMS can become complicated by respiratory, hepatic or renal failure, cardiovascular collapse, coagulopathy or gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Dantrolene is a direct acting muscle relaxant that can be beneficial in severe cases.