We cover Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM) from a recent Emergency Medicine Cases podcast and First10inEM blog post by Dr. Justin Morganstern regarding urinary tract infections (UTIs). This podcast and blog tackle common issues in UTI diagnosis and treatment, including the following points:

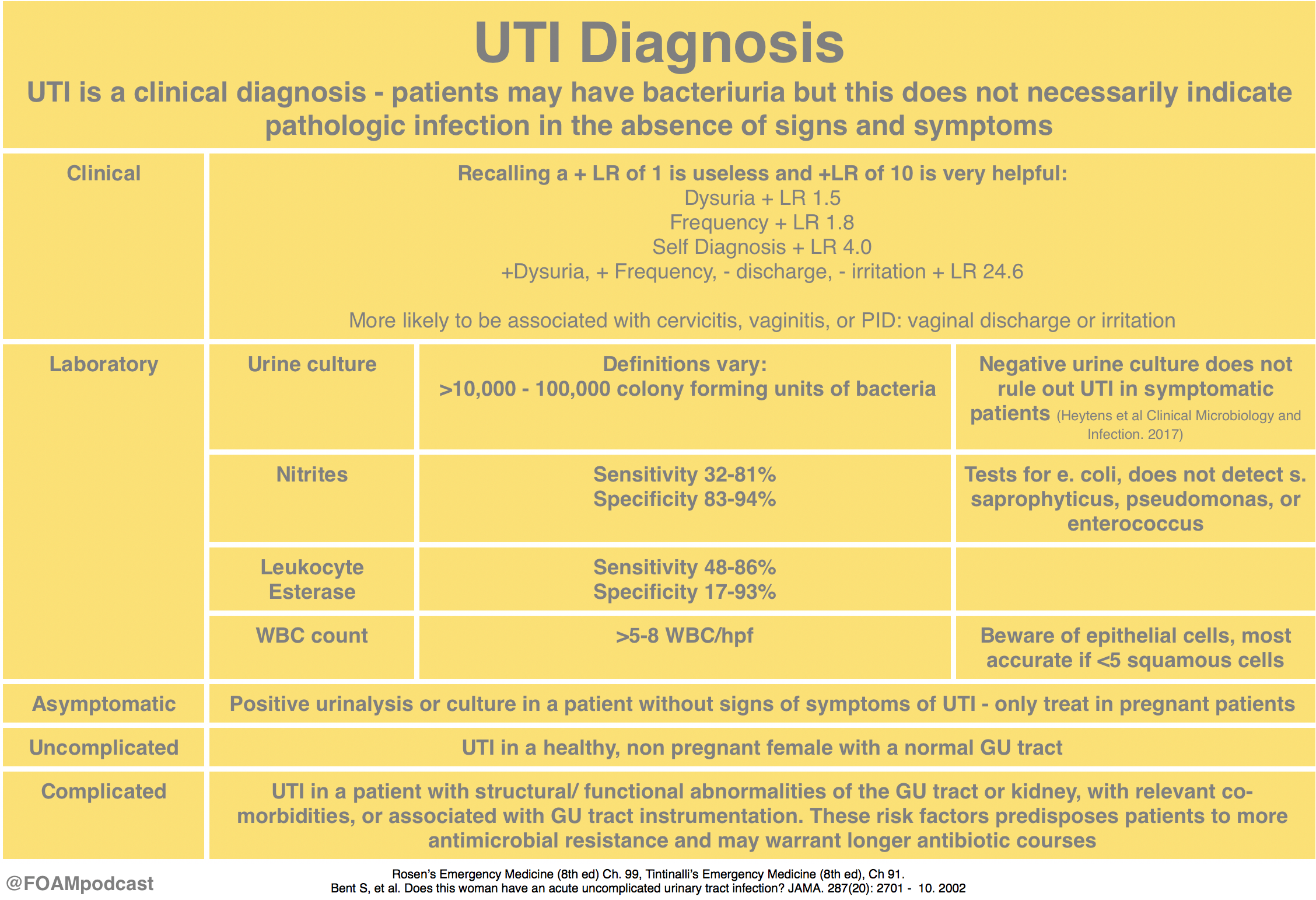

- UTI is a clinical diagnosis, a dirty urine does not mean the patient has a UTI

- Urinalyses are more complicated to interpret than we probably understand

The Core Content

Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (8th ed), Chapter 99; Tintialli’s Emergency Medicine (8th ed), Chapter 91; IDSA Guidelines for Treatment and Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 6-year-old girl presents with 4 days of lower abdominal pain. The patient complains of dysuria. On exam, the patient is afebrile and has mild tenderness to palpation in the suprapubic area. No costovertebral tenderness is elicited on exam. A clean-catch urine sample is sent for urinalysis. If positive, which of the following is the most specific to confirm the diagnosis?

A. Glucose

B. Leukocyte esterase

C. Nitrites

D. WBCs (>5 per high power field)

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

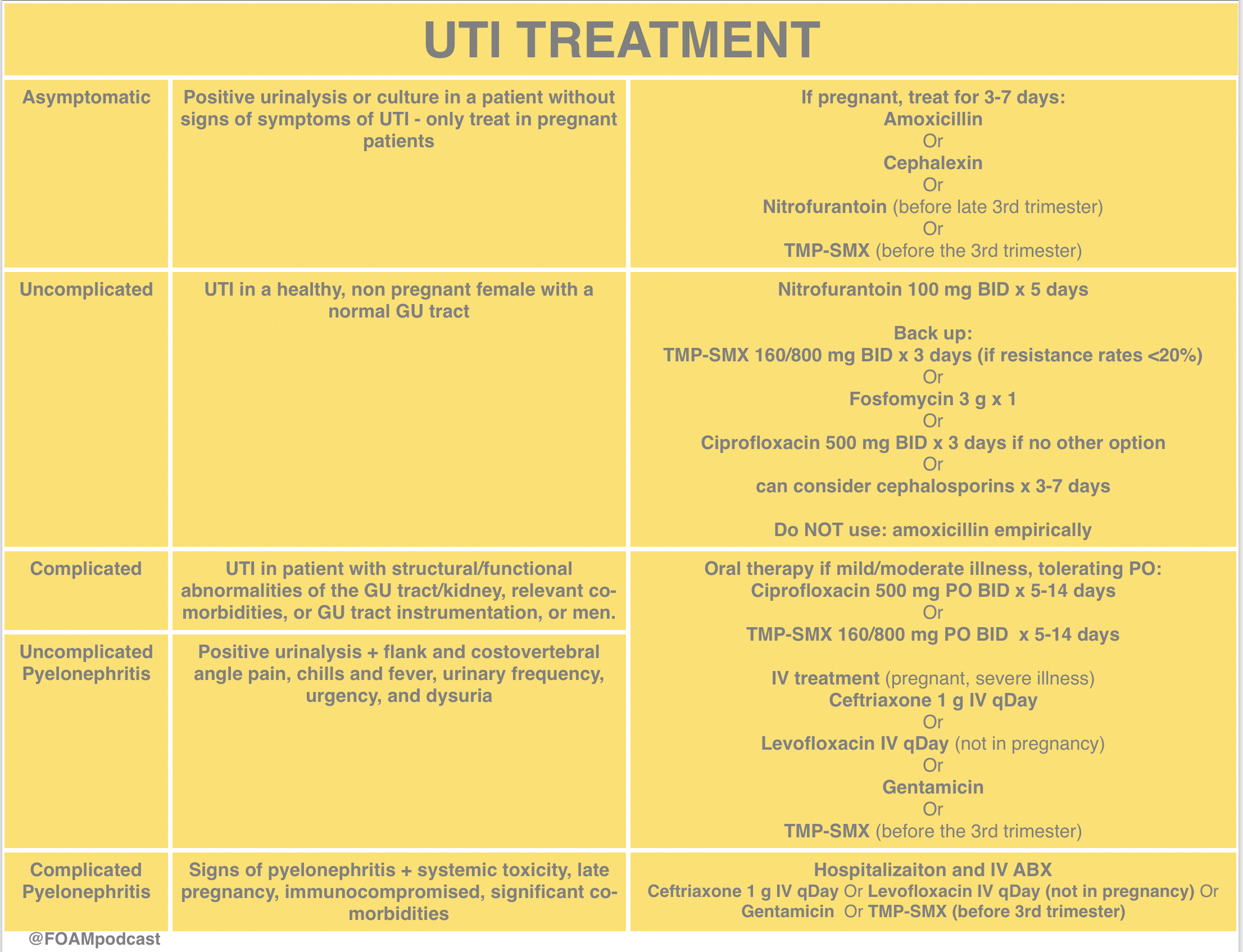

C. The patient’s presentation is consistent with an uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI). The most common cause of a UTI in children >1 year of age is E. coli. Nitrites normally are not found in urine but result when bacteria reduce urinary nitrates to nitrites. Many Gram-negative and some Gram-positive organisms are capable of this conversion, and a positive dipstick nitrite test indicates that these organisms are present in significant numbers (i.e., more than 10,000 per mL). This test is specific (92%–100%) but not highly sensitive (19%–48%). A positive result is helpful, but a negative result does not rule out UTI. The nitrite dipstick reagent is sensitive to air exposure, so containers should be closed immediately after removing a strip. After 1 week of exposure, 33% of strips give false-positive results, and after 2 weeks, 75% give false-positive results. Non-nitrate-reducing organisms also may cause false-negative results, and patients who consume a low-nitrate diet may have false-negative results.

Glucose (A) normally is filtered by the glomerulus, but it is almost completely reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. Glycosuria occurs when the filtered load of glucose exceeds the ability of the tubule to reabsorb it (i.e., 180–200 mg per dL). Etiologies include diabetes mellitus, Cushing’s syndrome, liver and pancreatic disease, and Fanconi’s syndrome. Leukocyte esterase (B) is produced by neutrophils and may signal pyuria associated with UTI. It has a sensitivity of 72%–97% and specificity of 41%–86%. Leukocyte casts in the urinary sediment can help localize the area of inflammation to the kidney. Organisms such as Chlamydia and Ureaplasma urealyticum should be considered in patients with pyuria and negative cultures. Other causes of sterile pyuria include balanitis, urethritis, tuberculosis, bladder tumors, viral infections, nephrolithiasis, foreign bodies, exercise, glomerulonephritis, and corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide use. Leukocytes (D) may be seen under low- and high-power magnification. Men normally have fewer than 2 white blood cells (WBCs) per HPF; women normally have fewer than 5 WBCs per HPF; >5 WBCs/HPF is associated with a 90%–96% sensitivity and 47%–50% specificity.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

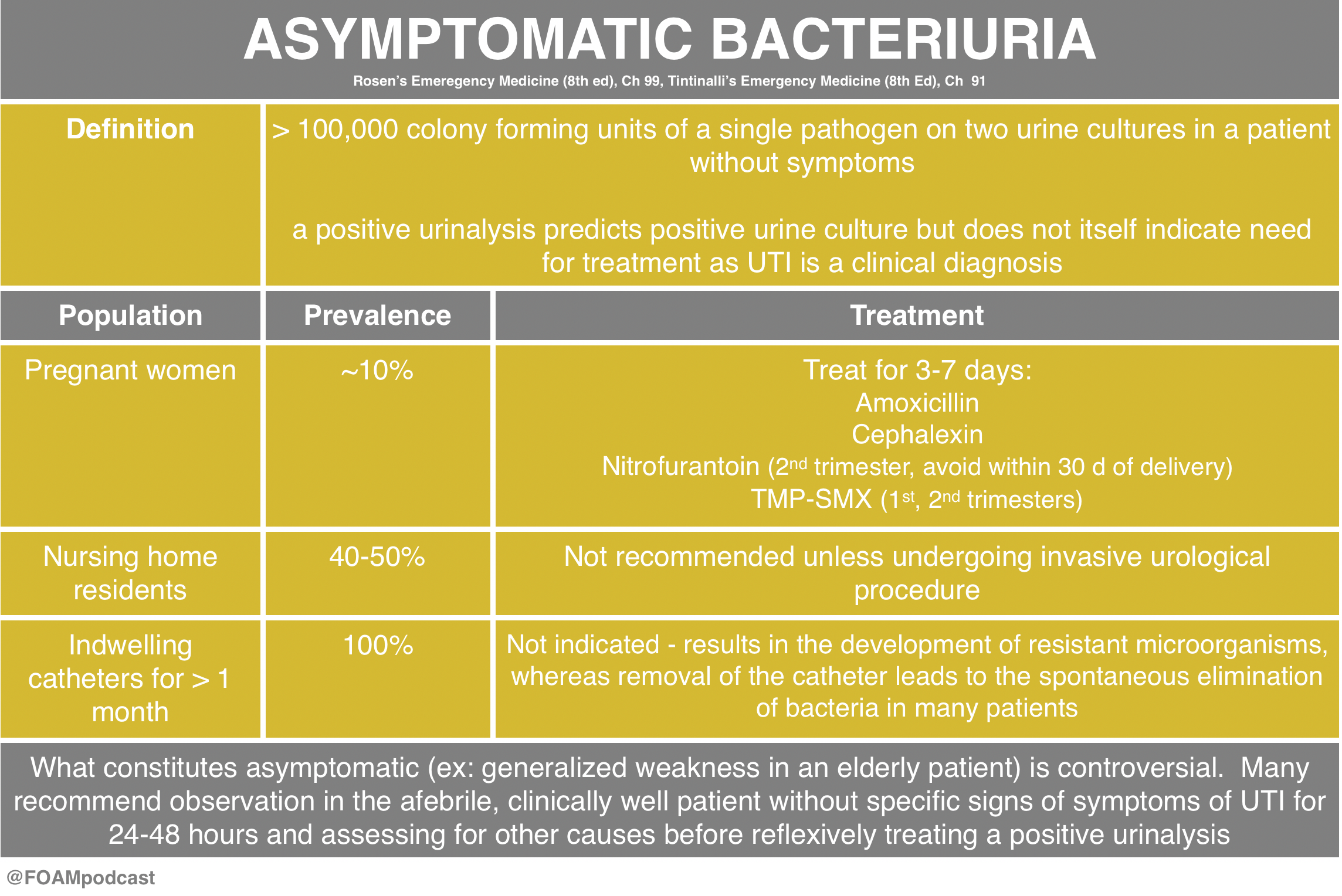

A 24-year old woman presents with URI symptoms. She is 32 weeks pregnant. As part of her work-up, you order a urinalysis, which shows 2+ bacteria with no WBCs. Two days later, the lab calls you and informs you that the urine culture is positive. You call the patient back and she denies symptoms of urinary tract infection. With regards to the urine culture results, what treatment is indicated?

A. Cephalexin 500 mg QID for 7 days

B. Ciprofloxacin 500 mg QID for 7 days

C. No treatment is necessary

D. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 1 DS tablet BID for 3 days

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

A. The patient has asymptomatic bacteriuria of pregnancy confirmed by a positive urine culture and should be treated with an oral antibiotic that is known to be safe in pregnancy, such as cephalexin 500 mg QID for 7 days. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common in the general population and in most scenarios does not require therapy. However due to the high risk of complication seen during pregnancy, it should be treated with antibiotics. It is seen in 2-10% of pregnant women and is commonly due to E. coli. Pregnant women have an increased risk of developing urinary tract infections due to the pressure that the enlarged uterus exerts on the ureters and bladder, incomplete emptying during voiding and impaired ureteral peristalsis from progesterone-induced relaxation of the ureteral smooth muscle. Complications of untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria include development of a lower urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, renal abscess, renal failure, bacteremia, sepsis, intrauterine growth retardation, premature labor and neonatal death. Treatment options generally include cephalosporins, such as cephalexin, amoxicillin (or amoxicillin-clavulanate) and nitrofurantoin. All of which are recognized as Category B by the Food and Drug Administration; meaning that animal studies have failed to show a risk to the fetus. Treatment duration should be for 7-10 days.

Ciprofloxacin (B) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (D) are Category C and D, respectively, and therefore should be avoided in pregnancy when possible. Because there is increased risk for complication during pregnancy, antibiotic treatment (C) is recommended.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References:

Gupta K et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis in Women: A 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Infect Dis (2011) 52 (5): e103-e120.

Nicolle L et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in Adults. Infect Dis (2005) 40 (5): 643-654.

Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th ed. Chapter 99.

Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine, 8th ed. Chapter 91.