iTunes or Listen Here

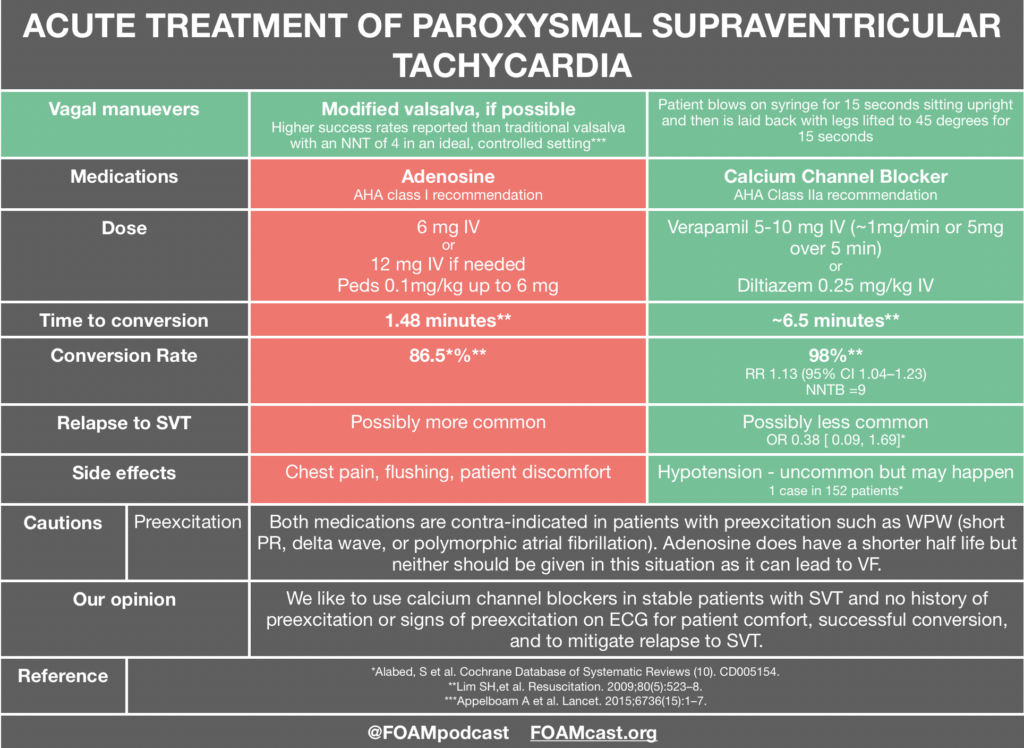

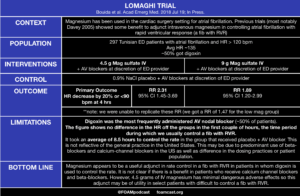

We have previously podcasted on tachyarrythmias (Episode 34 Tachyarrhythmias), but in this episode, we focus specifically on the treatment of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), specifically paroxysmal SVT.

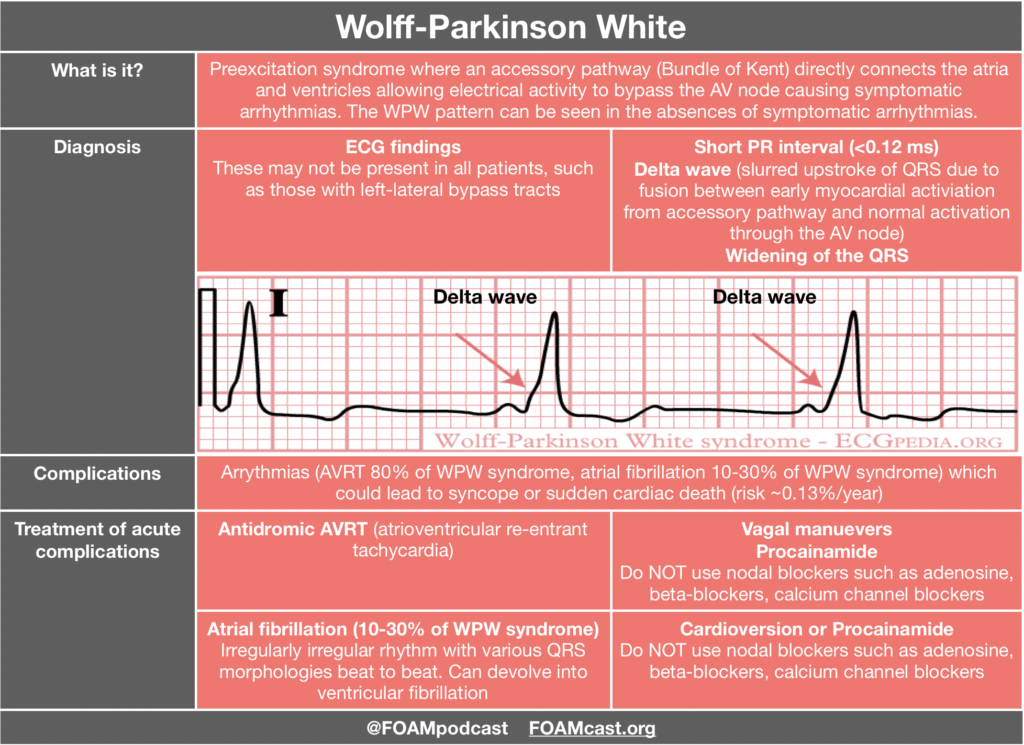

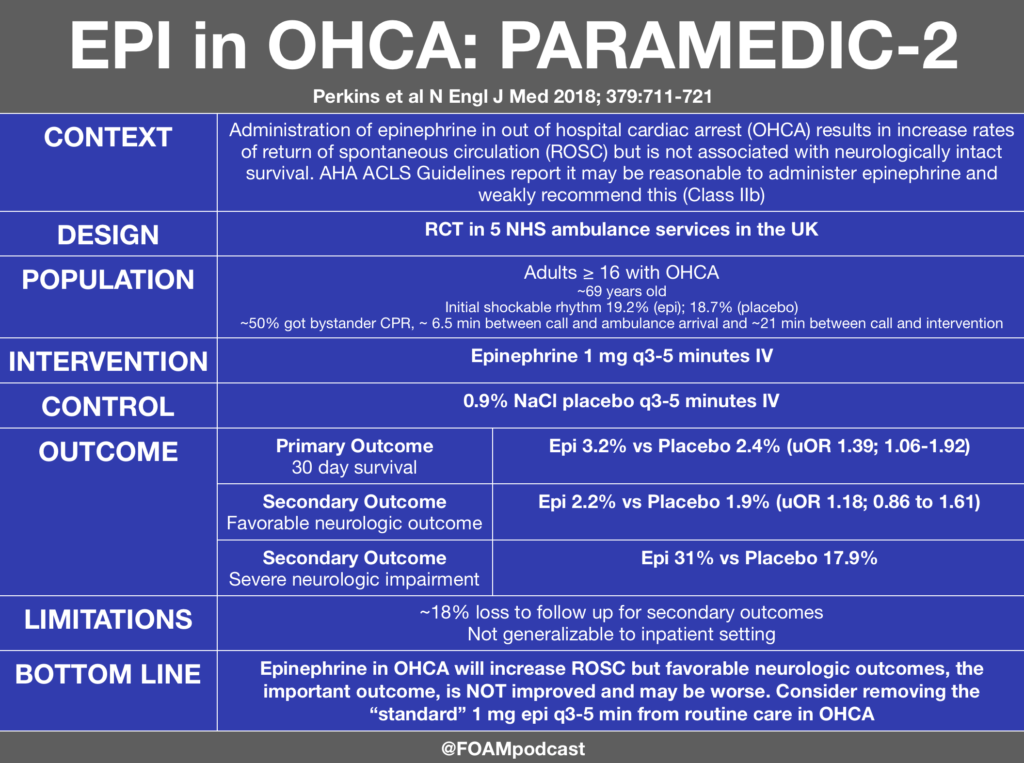

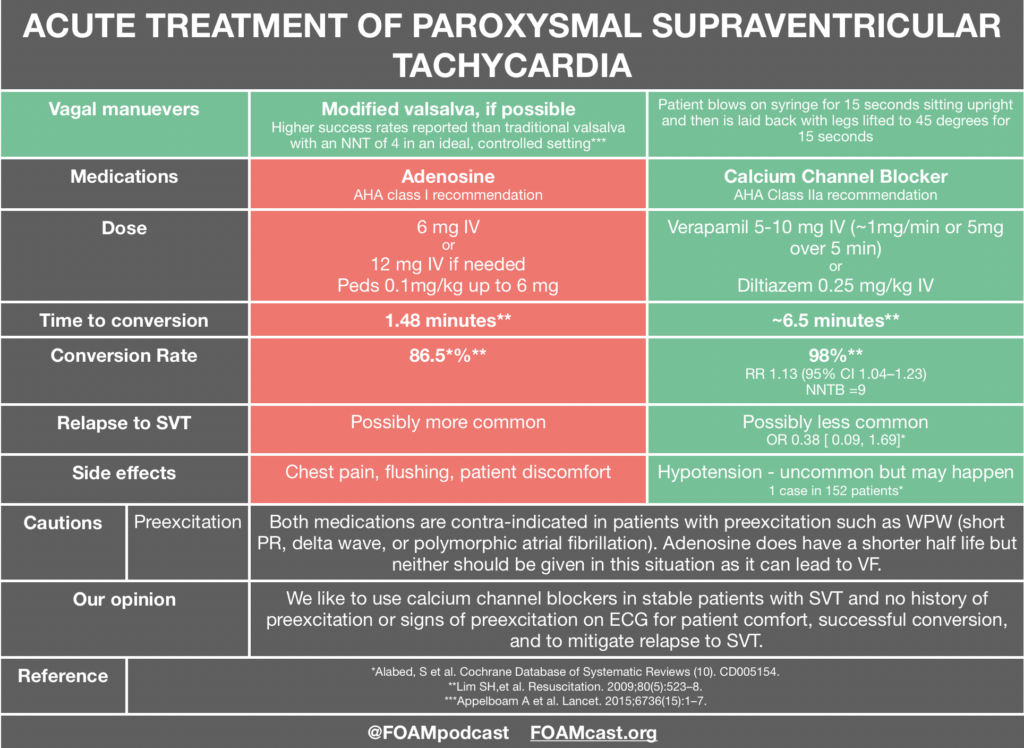

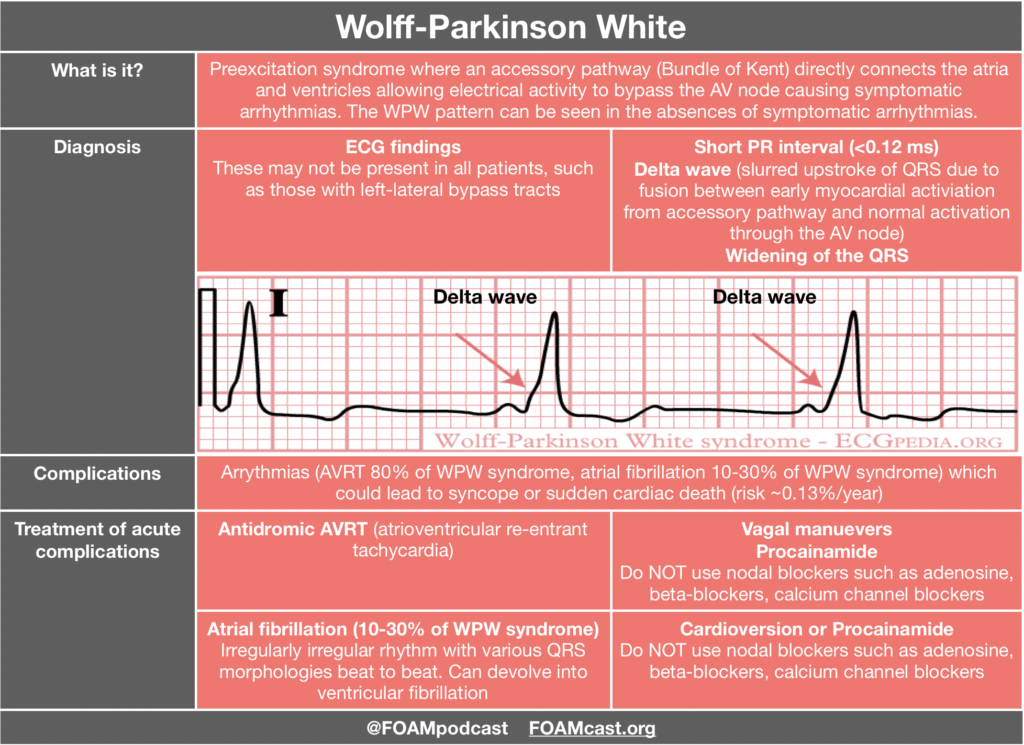

Adenosine and calcium channel blockers are both commonly used in the treatment of SVT; however, practice often varies by region. Advantages to adenosine are the short half-life but this comes with a trade-off of patients experiencing terrifying feelings as they have a sinus pause. Calcium channel blockers have the advantage of not causing those side effects and may prevent recurrence, but patients may infrequently experience hypotension [3,4]. Adenosine and calcium channel blockers are both contra-indicated in pre-excitation syndromes as they may precipitate ventricular fibrillation. A case series is often cited as a reason to not give calcium channel blockers in SVT; however, in these cases 4 of the 5 patients were treated for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response NOT SVT and all patients had signs of preexcitation on their ECG in which use of nodal blockers are discouraged [5]. Both adenosine and calcium channel blockers are recommended by the AHA [1]. In fact, the AHA recommendation for calcium channel blockers in SVT is higher than that for epinephrine in out of hospital cardiac arrest (which is a Class IIb recommendation).

Personally, we like calcium channel blockers for the treatment of stable SVT in patients who do not have signs of pre-excitation.

A 2-month-old male infant presents with rapid heart rate from the pediatrician’s office. The baby’s blood pressure is normal for age and he appears interactive with mom. ECG confirms your suspicion of supraventricular tachycardia. What is the mechanism of action of the medication of choice?

A. Blocks accessory pathway re-entry

B. Decreases conduction through the accessory pathway

C. Decreases conduction through the atrioventricular node and blocks atrioventricular nodal re-entry

D. Increases conduction through the atrioventricular node and blocks atrioventricular nodal re-entry

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

C. Adenosine is the pharmacologic treatment of choice for supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). It is a purine nucleoside that decreases the rate of conduction through the atrioventricular (AV) node and blocks AV nodal re-entry. It works directly on adenosine receptors at the AV node. By decreasing the rate of conduction, adenosine effectively slows the anterograde entry of SVT. By blocking AV nodal re-entry, it effectively stops retrograde conduction through the AV node. Thus, adenosine works well for SVT with and without accessory pathways. Adenosine is a very short acting medication and is metabolized quickly, so it should be given as close to the heart as possible. It should be administered through a large gauge peripheral IV, with a flush of 5 to 10 mL of normal saline, traditionally using a 3-way stopcock. SVT is the most common dysrhythmia in childhood. Often, children with SVT are relatively stable. Heart rates for infants are generally over 220 beats per minute and over 180 beats per minute in young children under 2 years old. In children who have normal mentation and stable blood pressures, IV access should be obtained and vagal maneuvers may be attempted. If a child is unstable, synchronized cardioversion at 0.5-1 J/kg should be performed as soon as possible. Cardiology should be consulted for further management, including accessory pathway ablation in many cases.

Adenosine does not block accessory pathway re-entry (A). Adenosine also does not slow forward conduction of the accessory pathway (B). It only works at the AV node and blocks AV re-entry. Adenosine is effective only at the adenosine receptors on the AV node. Adenosine does not increase conduction through the atrioventricular node (D) but rather decreases conduction at the AV node.

/toggle]

[/accordion]

References:

- Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):e27-e115.

- Appelboam A, Reuben A, Mann C, Gagg J, Ewings P, Barton A, et al. Postural modification to the standard Valsalva manoeuvre for emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardias ( REVERT ): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;6736(15):1–7.

- Alabed, S. orcid.org/0000-0002-9960-7587, Sabouni, A., Providencia, R. et al. (3 more authors) (2017) Adenosine versus intravenous calcium channel antagonists for supraventricular tachycardia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10). CD005154. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005154.pub4

- Lim SH, Anantharaman V, Teo WS, Chan YH. Slow infusion of calcium channel blockers compared with intravenous adenosine in the emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardia. Resuscitation. 2009;80(5):523–8.

- Mcgovern B, Garan H, Ruskin JN. Precipitation of cardiac arrest by verapamil in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104(6):791-4.