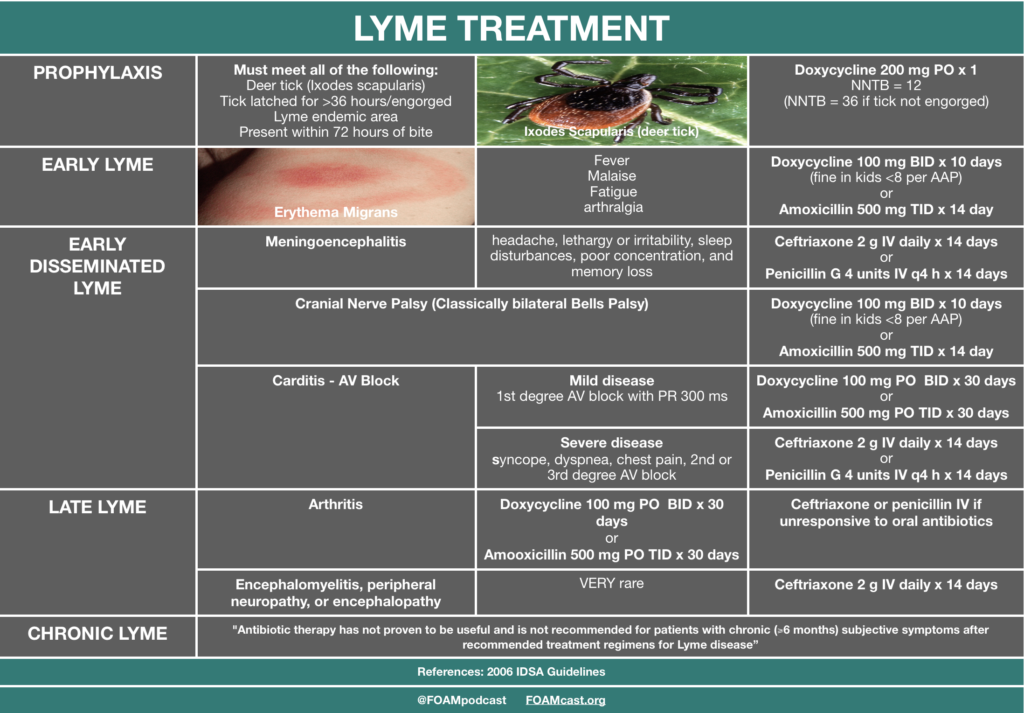

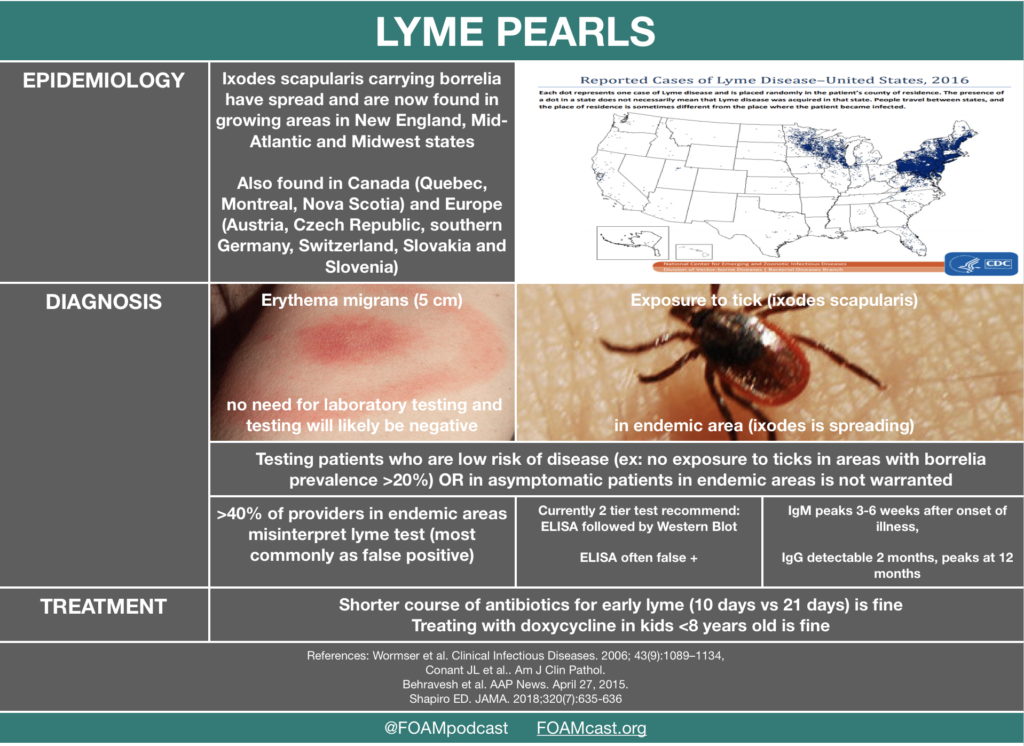

We cover a JAMA Clinical Reviews podcast on lyme disease, including some myth-busters.

- Doxycycline can be used, safely, in kids < 8 years old [1].

- Testing for lyme is a mess because :

- (1) we test patients with an ultra low probability of disease

- (2) we test patients who shouldn’t be tested (i.e. have erythema migrans and thus very high probability)

- (3) the tests are a pain to interpret and many clinicians (42.4% in lyme endemic Vermont) misinterpret tests, most commonly as false positive [2].

- Lyme disease is spreading further south and west in the US, into Canada, and it’s also increasingly found in Europe [3,4].

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 32-year-old man with a history of hypertension and sickle cell disease presents to the ED for intermittent fevers. He has been feeling ill for the past few weeks with intermittent headaches, night sweats, and abdominal pain. He recently returned from Maine after a trip to see the fall colors. His vital signs are only remarkable for a temperature of 100.7oF. Physical exam reveals mild scleral icterus and hepatomegaly. The patient’s Wright stain shows intraerythrocytic rings. What co-infection is common in this disease?

A. Babesia microti

B. Borrelia burgdorferi

C. Francisella tularensis

D. Rickettsia rickettsii

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

A.This patient’s presentation is consistent with acute babesiosis infection. Patients are commonly co-infected with Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) or ehrlichiosis. Risk factors include functional or surgical asplenia, immunocompromised state, and advanced age. This patient likely has functional asplenia given his age and history of sickle cell disease. Diagnosis is confirmed with a Wright or Giemsa stain showing intraerythrocytic rings, similar to malaria. Babesiosis is due to Babesia parasite and transmitted via the Ixodes deer tick. Patients present with a wide array of symptoms from a vague viral syndrome-type symptoms and spiking fevers to hepatomegaly and hemolytic anemia. Patients with risk factors tend to have more severe features including severe hemolysis, jaundice, renal failure, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Treatment is with atovaquone and clindamycin or azithromycin.

[/toggle]

[/accordion

Which of the following would be the best antibiotic choice for first-line treatment of a 5-year-old who presents to your office with multiple erythema migrans lesions but no cardiac or neurological symptoms?

A. Amoxicillin PO for 14 to 21 days

B. Azithromycin PO for 14 to 21 days

C. Doxycycline PO for 10 to 21 days

D. Ceftriaxone IM for 14 days

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

***This is an example of the difference between practice and board exams, which tend to lag behind current knowledge.

Correct-Answer: Amoxicillin PO for 14 to 21 days. Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness that is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, making it a spirochetal infection. When deciding the medical therapy for Lyme disease, staging is important. Early localized disease usually presents with a “bullseye rash,” otherwise known as erythema migrans. Patients in this stage of disease may have a few constitutional symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, and myalgias. Early disseminated disease is present if patients have multiple erythema migrans, cardiac or neurologic findings. Late disease usually involves persistent arthritis of a large joint or more severe neurological findings such as encephalopathy or polyneuropathy. In the case above, amoxicillin is the best choice of treatment because the patient is under 8 years of age, and, while multiple lesions are present, the patient does not have neurological or cardiac involvement and should be treated with the same therapy as if he had a single lesion. Recommended duration of therapy is between 14 and 21 days. The goal of therapy is to reduce the risk of developing late Lyme disease and to shorten the duration of symptoms. Azithromycin PO for 14 to 21 days (B) is not recommended as a first-line treatment for Lyme disease because it is less effective than amoxicillin. There has been documented resistance to macrolides by some strains of Borrelia burgdorferi. Doxycycline PO for 10 to 21 days (C) is not recommended in this case because of the patient’s age. Tetracyclines are not recommended for children under 8 years of age because they can lead to permanent staining of their teeth. Ceftriaxone IM for 14 days (D) is not recommended because oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline, are just as effective for treatment of erythema migrans and make for easier administration.

[/toggle]

[/accordion

References:

- Todd S et al. No Visible Dental Staining in Children Treated with Doxycycline for Suspected Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. The Journal of Pediatrics. May 2015. Volume 166, Issue 5, Pages 1246–1251

- Conant JL, Powers J, Sharp G, Mead PS, Nelson CA. Lyme Disease Testing in a High-Incidence State: Clinician Knowledge and Patterns. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;149(3):234-240.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Accessed 9.22.2018

- Infectious Disease Society of America’s 2006 Lyme Guidelines

- Min Han J et al. Comparative effectiveness and toxicity of oral antibiotics for early Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. ECCMID abstract . 2017.

- Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. Chapter 160 “Zoonotic infections.”

- Rosen’s Emergency Medicine. (8 ed) . Chapter 126 “Tickborne Illnesses”