(ITUNES OR Listen Here)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

Dr. Ryan Radecki of Emergency Medicine Literature of Note reviews Gestational Age D-Dimers covering an article by Murphy and colleagues in BJOG.

The paper: The authors took blood samples from 760 healthy pregnant patients at one point during their pregnancy. They propose a continuous increase for a normal d-dimer cut off throughout gestation.

- 1-12 weeks: n=33, 81% with normal d-dimer

- 19-21 weeks: n=53, 32% with normal d-dimer

- 28-36 weeks: n=8, 6% with normal d-dimer

- 39-40 weeks: 0, 0% normal d-dimer

- Postpartum day 2: n=12, 8% with normal d-dimer

Dr. Radecki’s “Take Home:“

- Dr. Kline has advocated for the following d-dimer cut offs in pregnancy: 1st trimester 750 ng/mL, 2nd trimester 1000 ng/mL, and 3rd trimester 1250 ng/mL(based on a standard cut-off of 500 ng/mL) and this may be reasonable but is not rooted in robust evidence.

Interestingly, this post was followed by another post covering an article by Hutchinson et al from Am J Roentgenol showing that of 174 CTPAs initially read as positive, 45 were read as negative by chest radiologist upon blinded retrospective review. That means 25.9% of this cohort diagnosed with PE apparently had negative CT scans.

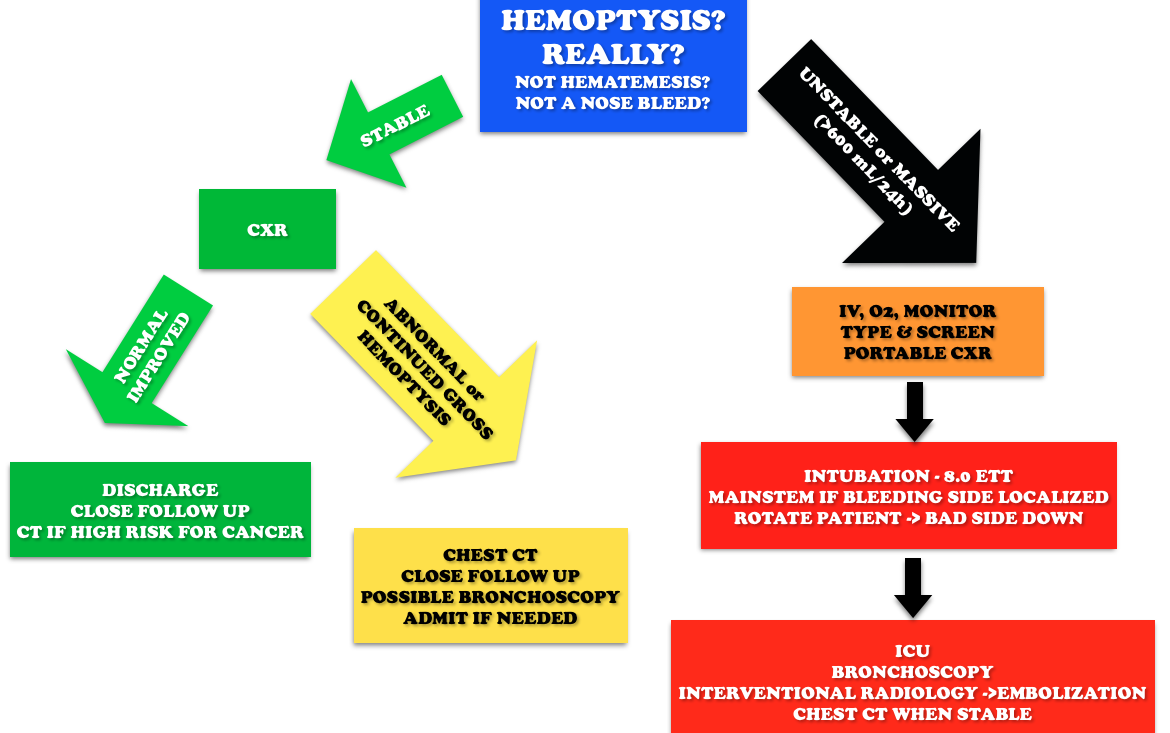

Core Content – Hemoptysis

Tintinalli (7e) Chapter 66; Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (8e) Chapter 24

Etiology: Most common causes are bronchitis (often blood tinged sputum), infection (abscess, pneumonia, tuberculosis), neoplasm (lung cancer). Other causes include iatrogenic causes (bronchoscopy, biopsy, aspirated foreign body), anticoagulation, and autoimmune diseases such as granulomatous polyangiitis (Wegener’s), lupus, and Goodpasture’s.

Workup:

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. A 50-year-old man, nonsmoker, presents to the ED with a 2-day history of cough now associated with frank hemoptysis. He denies any constitutional symptoms. Vital signs are BP 125/70, HR 80, RR 16, and pulse oximetry is 98% on room air. On exam, his lung fields are clear; the remainder of the exam is unremarkable. A chest radiograph is performed, which is normal. [polldaddy poll=9039260]

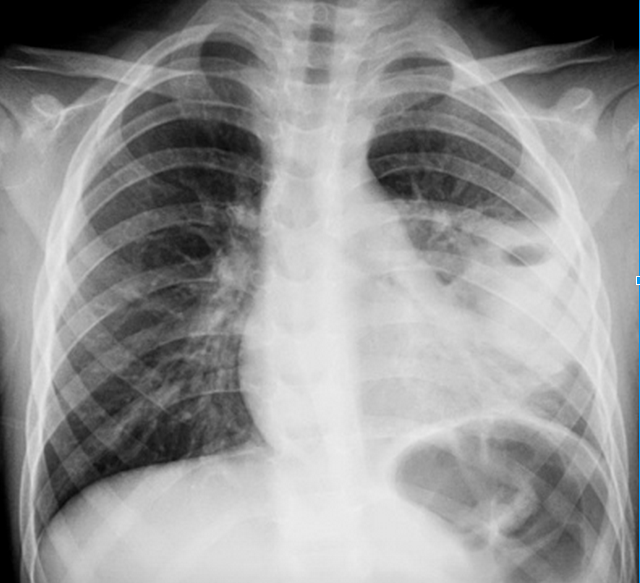

Question 2. A 55-year-old man, smoker, presents to the ED with hemoptysis and dyspnea for 4 weeks. His VS are T 37°C, BP 146/76 mm Hg, HR 85 bpm, RR 20 per minute, and oxygen saturation 96% on RA. His lung exam reveals distant breath sounds on the left side. His chest X-ray is shown below. [polldaddy poll=9039262]

Answers

1.C. The patient is hemodynamically stable with a normal chest radiograph, so he does not require ICU admission (A). Patients with massive hemoptysis require ICU admission. The decision to perform a bronchoscopy (B) in this patient will be left up to the pulmonologist. Given the overall clinical picture, urgent bronchoscopy is not required in this case. With massive hemoptysis, an emergent bronchoscopy is indicated. Bronchitis (D) typically presents with the abrupt onset of cough with blood-streaked purulent sputum. The patient in the clinical scenario has persistent frank hemoptysis, which mandates further investigation. In a patient who does not smoke, is under the age of 40, and has a normal chest radiograph and scant hemoptysis, treatment for bronchitis can be initiated with outpatient follow-up.

2. B. Although bronchitis (A) is the most common cause of hemoptysis (responsible for 15%-30% of cases), patients present with cough as the dominant symptom and have abnormal lung exams and normal chest x-rays. The cough may be productive of sputum. The diagnosis of pneumonia (C) requires focal findings on physical exam or infiltrates on radiographic imaging and is typically accompanied by a fever. Patients with lung cancer are at increased risk for pulmonary embolism (D). This patient’s Wells score is 2 (one point each for hemoptysis and malignancy), which makes the likelihood of PE 16% in an ED population. Given the lung mass seen on chest x-ray, lung cancer is more likely than PE.

References: