(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

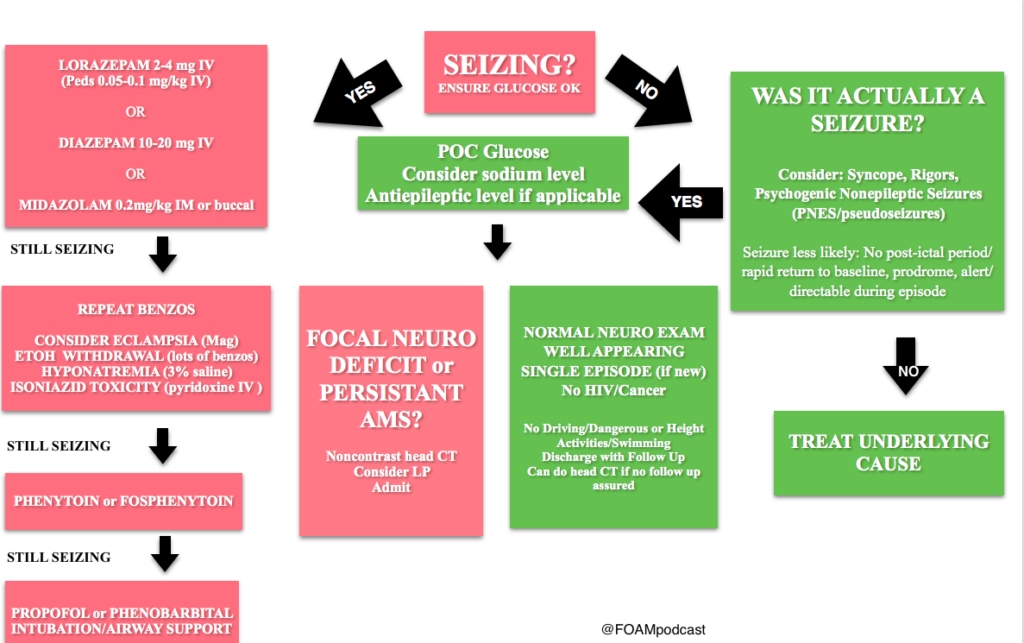

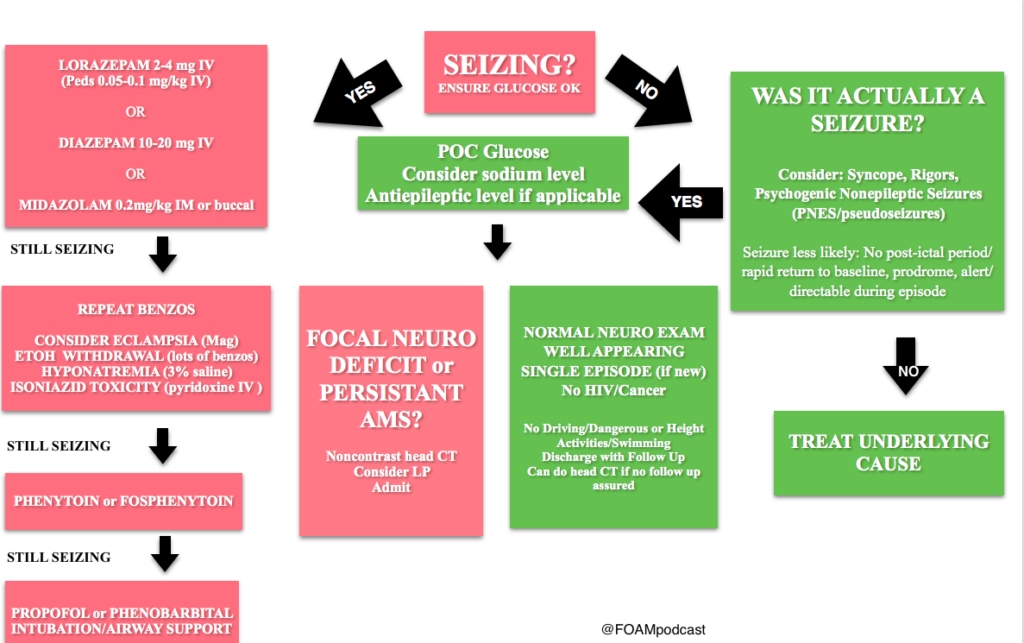

We cover Special Seizures from EMin5.com by Dr. Anna Pickens. This is a short video summarizing important diagnoses to consider when a seizure doesn’t stop after the first or second round of benzodiazepines.

[expand title=”Female“]

Consider eclampsia, which typically occurs >20 weeks gestation to 6 weeks post-partum. Magnesium 4-6 grams IV, followed by infusion. Watch for apnea, check reflexes. [/expand]

[expand title=”Possible history of alcohol abuse“]

Consider alcohol withdrawal seizure. These patients respond to benzodiazepines and will typically NOT respond to antiepileptics such as phenytoin. They just need larger doses of benzodiazepines, so ramp up the dosages of those (10-100 mg of diazepam) and may require phenobarbital or propofol. [/expand]

[expand title=”Possible isoniazid exposure“]

Isoniazid toxicity can cause seizures, coma, metabolic acidosis, often within only 30 minutes of ingestion. The treatment here is pyridoxine (vitamin B6). These patients will need large doses and many recommend empirically giving 5 GRAMS intravenously (note: this is takes many vials as the typical dose of this medication is 50-100 MILLIGRAMS). This is a great review by First10inEM [/expand]

[expand title=”Consider hyponatremia“]

Treat with 100 mL of 3% hypertonic saline over 10-15 minutes. Can repeat x 1. Beware of rapidly correcting sodium in these patients due to central pontine myelinolysis/osmotic demyelination syndrome. [/expand]

Core Content

We delve into core content on seizures using Rosen’s (8th edition) Chapter 18 and Chapter 171 in Tintinalli (8th edition)

Febrile Seizures AAP Guidelines

Febrile Seizures

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

A fifteen-year-old girl presents for evaluation and clearance for sports play. She has played team sports in the past, and would like to join the swim team this year. She was recently diagnosed with a seizure disorder. Her seizures are usually in the mornings, are generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and last for 1-2 minutes. They occur once per week. She is currently taking topiramate for seizure control. Her physical exam and vital signs are reassuring. Which of the following is the best recommendation for this patient?A. Allow participation in swimming as this is not a contact sport

B. Deny participation in all sports until seizures are better controlled

C. Permit patient to join the swim team as long as she has rectal diazepam with her at all times

D. Refuse participation in swimming as seizures are poorly controlled

[expand title=”Answer”]

D. Refuse participation in swimming as seizures are poorly controlled. Swimming (A) is a danger to children with poorly controlled seizures, as there is a risk that the child will have a seizure during the exercise and could suffer near-drowning or death. Some sporting events are safe for children with epilepsy (B), such as running. While the child participating in non-contact and non-aquatic sports may still have a seizure, the risk of morbidity and mortality to the child and other participants is low. Rectal diazepam (C) is a pharmacologic therapy that can stop seizures once they begin; however, the risk for morbidity and mortality remains high for children with poorly controlled seizures.

[/expand]

A full-term 3-week-old girl is brought in by her parents who report that she has been “acting funny” for 2 hours. They noticed that she has been moving her lips nonstop. She was a full-term, normal, spontaneous vaginal delivery and has been feeding well with adequate wet diapers since hospital discharge. She is afebrile and vital signs are normal. The anterior fontanelle is flat, and red reflexes are present. Heart, lung, and abdominal exams are normal. Her neurologic exam is positive for root, suck, and Moro reflexes, upgoing Babinski reflexes, and rhythmic lip-smacking movements. What is the most appropriate next step to take with this baby?

A. Administer a benzodiazepine

B. Initiate EEG monitoring

C. Perform a CT scan of the brain

D. Provide reassurance that this is normal behavior

[expand title=”Answer”]

This baby is having neonatal seizures, which are often subtle and more likely to be focal than tonic clonic. The most common manifestations are lip smacking, eye deviation, staring, rhythmic blinking, and bicycling movements. The patient should receive a benzodiazepine, such as lorazepam, midazolam, or diazepam, to stop the seizure. This should be followed by a workup that is directed at finding the underlying cause because neonatal seizures are less likely to be idiopathic than seizures in older children. A full septic workup is mandated for neonates with seizures, whether or not they are febrile. This includes CBC, blood culture, chemistry, UA, urine culture, chest x-ray, and CSF analysis. The infant should receive antibiotics and acyclovir and should be admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. Trauma can also cause neonatal seizures. It is important to look for signs of trauma such as bruising, bulging fontanelles, and retinal hemorrhages; the history may also include poor feeding, lethargy, or vomiting. Any infant with suspected head trauma should have a CT scan (C) and undergo a full child-abuse workup. An EEG (B) can be considered after more life-threatening causes of seizures, such as infection or trauma, are ruled out. A newborn (< 1 month old) with abnormal behavior should never be sent home with parental reassurance (D) only. Many new parents mistake normal behaviors for abnormal ones, but any truly abnormal behavior needs further investigation.[/expand]

References:

Kornegay JG. Chapter 171: Seizures Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Review (8e).

McMullan JT, Davitt AM, Pollack CV. “Seizures.” Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, Chapter 18, 156-161.e1