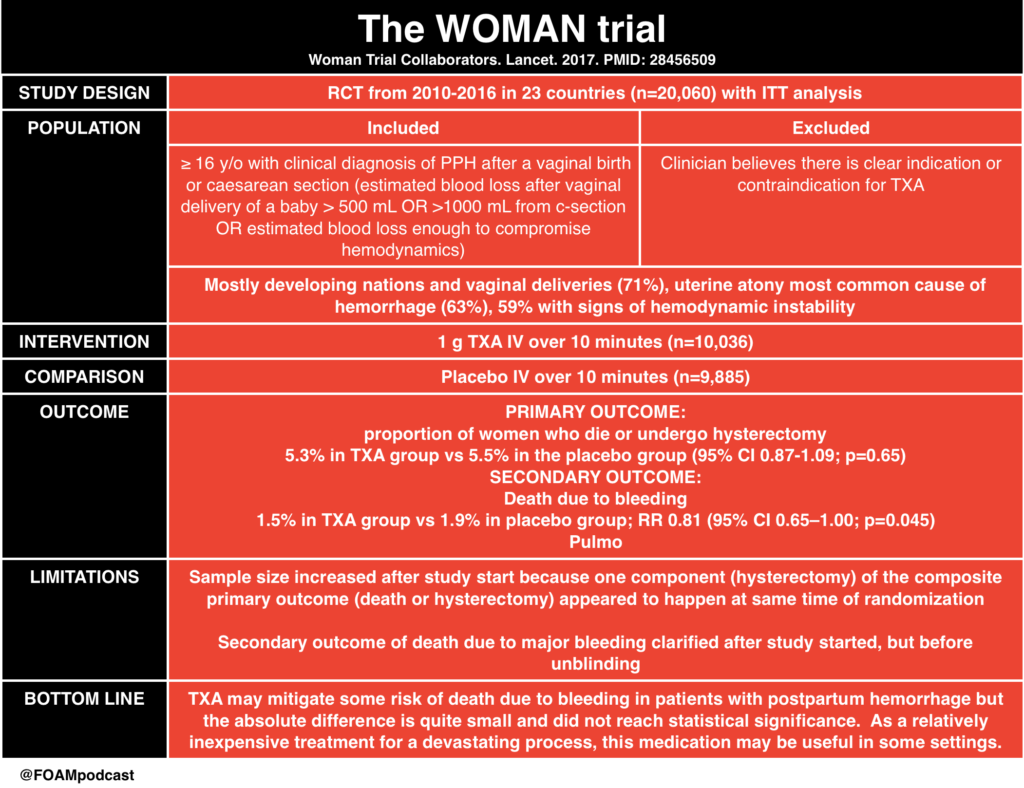

The WOMAN trial of tranexamic acid (TXA) for post-partum hemorrhage has been covered well by several free open access medical education (FOAM) sources. We review the trial and coverage from the following excellent sites:

The Core Content

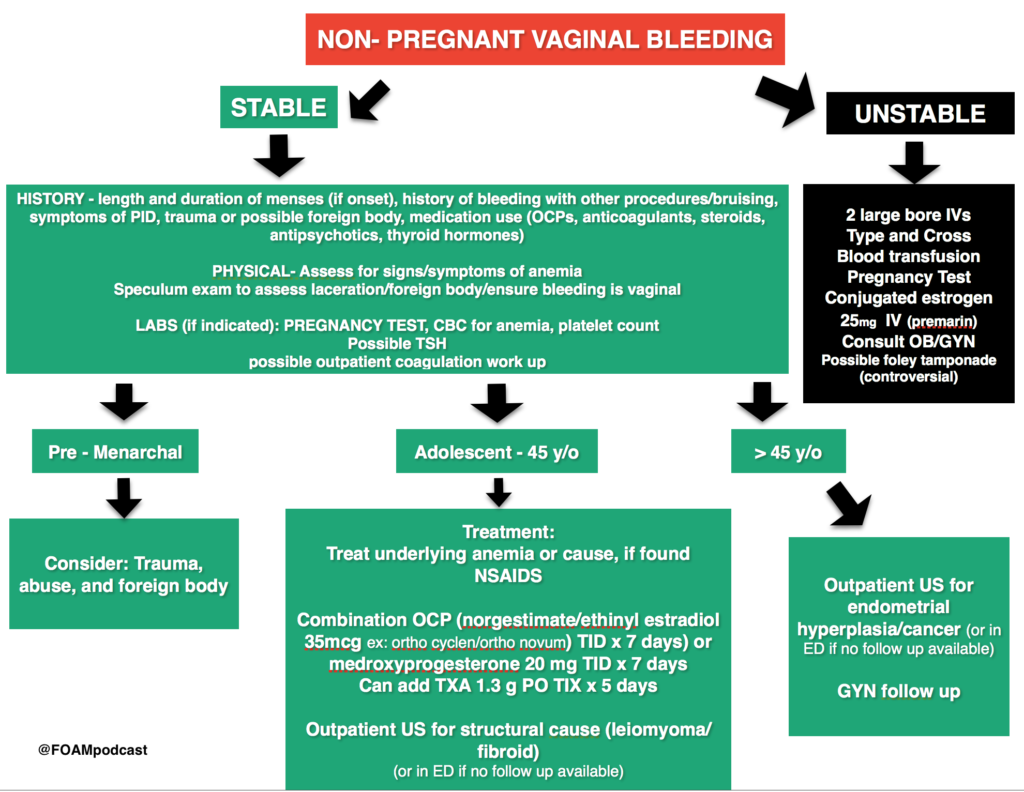

We have previously covered vaginal bleeding after the first trimester and ectopic pregnancies and first tri, ester vaginal bleeding. In this episode we cover non-pregnant vaginal bleeding using Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (8th ed), Chapter 100 , Tintialli’s Emergency Medicine (8th ed), Chapter 96 and the ACOG guidelines as guides.

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

A 32-year-old woman presents with vaginal bleeding for 2 weeks. She states she has about 1 pad of bleeding every 2-3 hours. Vital signs are stable and physical exam only reveals blood from the cervical os. The patient’s hemoglobin is 12 g/dl and her pregnancy test is negative. What treatment is indicated for this patient?

A. Admission for dilation and curettage

B. Combination oral contraceptives

C. Hysterectomy

D. Intravenous estrogen therapy

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”] B. This patient presents with non-life threatening dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB), which can initially be managed with combination oral contraceptives. DUB is typically split into anovulatory (90%) and ovulatory (10%). In patients with vaginal bleeding of childbearing age, the most important first step in diagnosis is to rule out pregnancy. After this, it is important to explore other causes including medications, genital tract pathology and systemic disease. Once these are excluded, a diagnosis of DUB can be reached. Some treatments include NSAIDs that inhibit PGE1 production and can both relieve cramping and pain and also decrease bleeding. In anovulatory bleeding, combination oral contraceptive pills can aid in regulating the menstrual cycle and counteract the effects of unopposed estrogen. Typically, patients are instructed to take combination oral contraceptive pills twice a day for 5-7 days or until the bleeding stops followed by once daily dosing. Dilation and curettage (A) is typically offered to patients with heavy vaginal bleeding evidenced by hemodynamic instability. A hysterectomy (C) is rarely needed in the treatment of DUB but is indicated for patients with heavy bleeding and hemodynamic instability in which conservative management fails. Intravenous estrogen therapy (D) is effective in stopping heavy bleeding, but is not considered first line therapy.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

A 55-year-old postmenopausal woman presents with a complaint of vaginal bleeding. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in management?

A. Abdominal ultrasound

B. Endometrial biopsy

C. Hysterectomy

D. Watchful waiting

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

Vaginal bleeding after menopause is an abnormal finding. The most common cause of vaginal bleeding after menopause is atrophy of the vaginal mucosa or endometrium, however 5-10% of postmenopausal women with vaginal bleeding have endometrial cancer. Endometrial cancer is potentially lethal, therefore any postmenopausal woman who presents with vaginal bleeding needs to be evaluated to rule out this etiology. After a careful history and physical exam, initial diagnostic testing to rule out endometrial cancer involves either endometrial biopsy or transvaginal ultrasound. Advantages of an endometrial biopsy include its high sensitivity, low cost and low incidence of complications. Women who need evaluation of the adnexa or myometrium, or who can’t tolerate endometrial biopsy should be referred for transvaginal ultrasound. If either test is inconclusive, further testing is warranted. Cervical cancer screening should also be a part of the workup for postmenopausal vaginal bleeding.

Abdominal ultrasound (A) is not recommended for women with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. If ultrasound needs to be used, transvaginal ultrasound is the appropriate diagnostic test to order. Postmenopausal women with an endometrial thickness < 3-4 mm on transvaginal ultrasound are unlikely to have endometrial carcinoma. Hysterectomy (C) may be indicated based on the results of the diagnostic imaging, but is not an initial step in management of postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. All women who present with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding should be evaluated with either endometrial biopsy or transvaginal ultrasound, there is no role for watchful waiting (D).

[/toggle]

[/accordion]