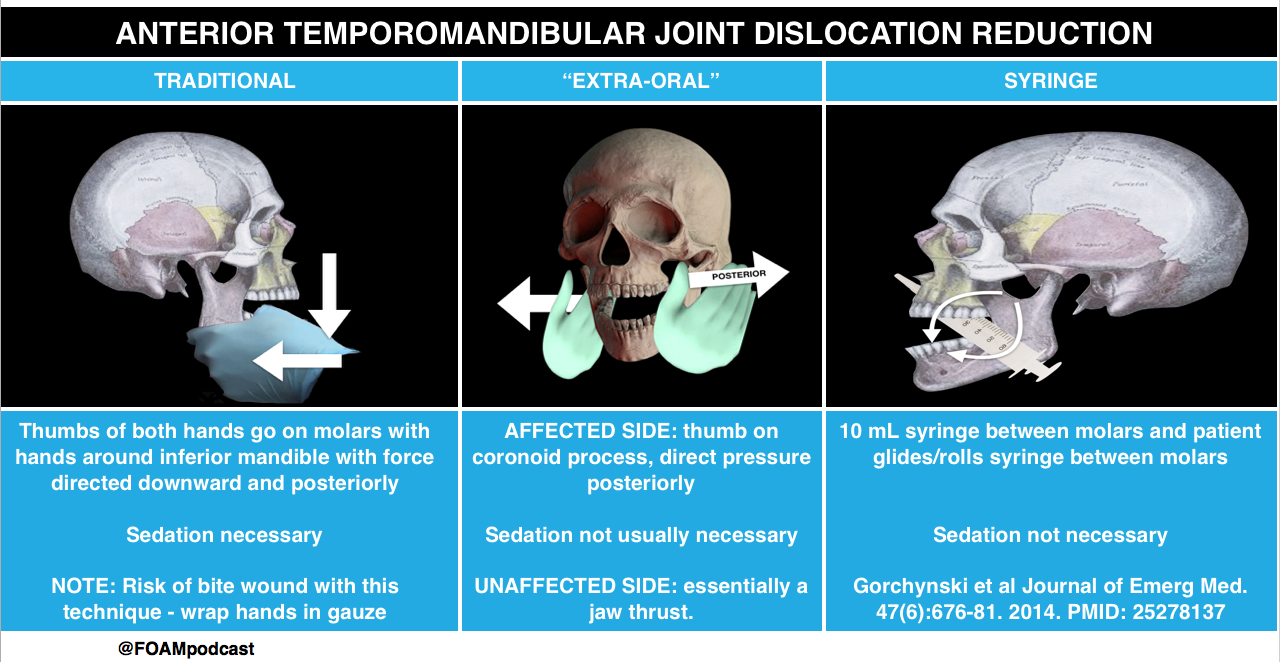

We review a trick of the trade from Academic Life in Emergency medicine for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dislocation, the extra-oral reduction.

Traditional Approach to TMJ dislocation and Syringe Technique from Core EM

Core Content

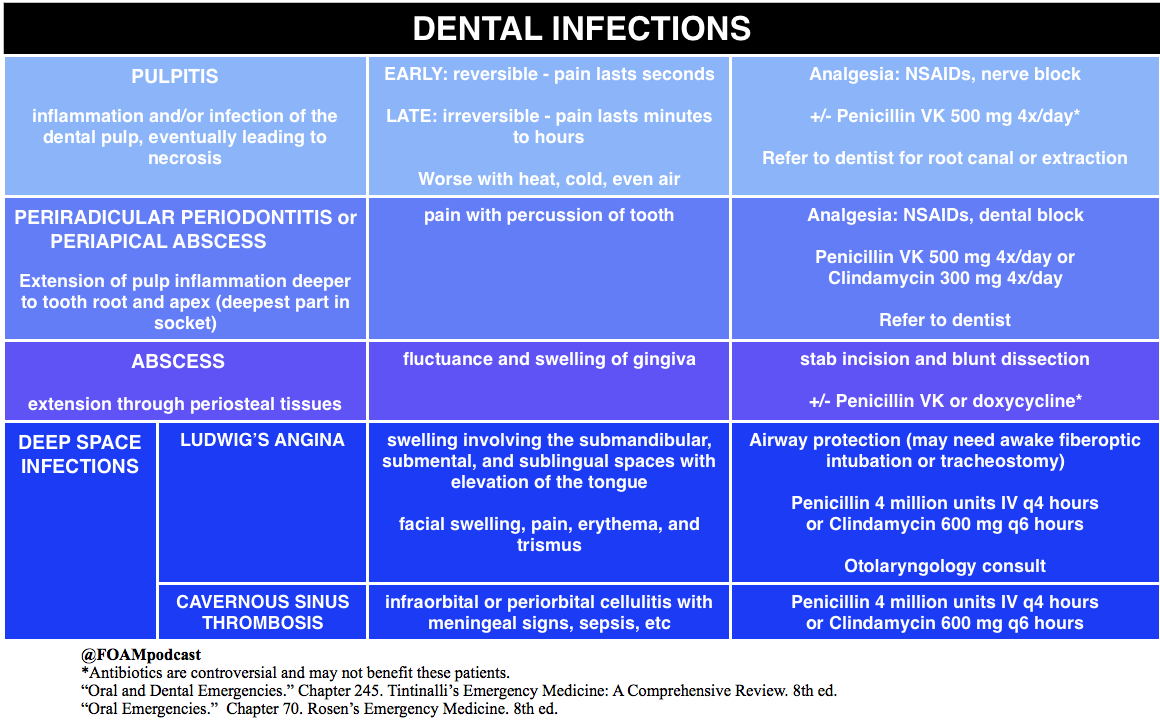

We delve into core content on dental injuries using Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) Chapter 70 “Oral Emergencies” and Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) Chapter 245 “Oral and Dental Emergencies” as a guide.

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

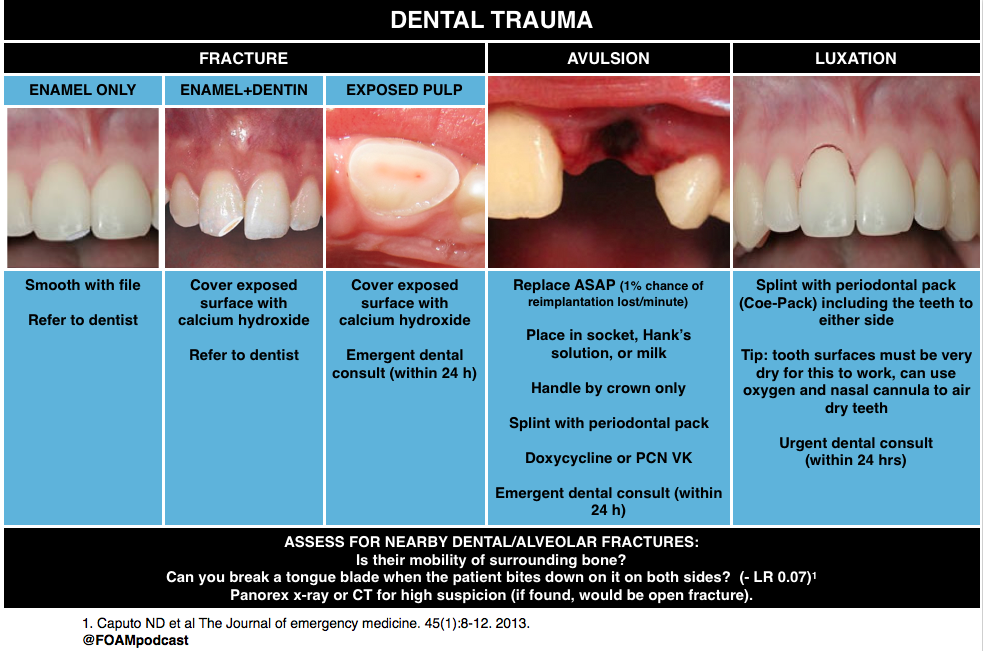

A 19-year-old man presents to the Emergency Department with an avulsed tooth. He struck his mouth on the back of another player’s head while playing basketball. He arrives thirty minutes after the injury with his right maxillary central incisor in a bag of cold milk. Which of the following is the most appropriate management?

A. Discharge home with next day dental follow up

B. Fill the alveolar socket with eugenol oil

C. Reimplant the avulsed tooth

D. Scrub the tooth with normal saline

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

C. Reimplant the avulsed tooth (B) is the most appropriate next step. Avulsed permanent teeth should be reimplanted as soon as possible, ideally within 30 minutes of the injury. For every minute that the tooth is out of its socket, there is a 1% chance of reimplantation failure. If the tooth is not able to be reimplanted immediately, it should be stored in an appropriate medium. Cold milk is preferable to sterile water or saliva as it has magnesium and calcium. Hank’s solution, a neutral cell culture medium, is ideal. Once the tooth is reimplanted, the tooth should be stabilized until dental follow up is arranged. Avulsed primary teeth should not be reimplanted.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

A 25 year-old man presents after falling face forward off his bike. He sustained an abrasion inside his upper lip and complains of a broken front tooth. He brought the fractured fragment with him. On examination, the bony structures of the jaw are non-tender. There is no malocclusion. Tooth #8 has a fracture and in the center of the exposed area is a small pink dot. What is the most appropriate plan for this patient?

A. Dental follow-up within the next 24 hours

B. Irrigation of the tooth

C. Placement of the tooth fragment in Hank’s solution

D. Viscous lidocaine for pain control

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

A. This patient has a dental fracture with exposed pulp. This is a dental emergency requiring dental follow-up within the next 24 hours. The most superficial dental fractures involve only the enamel on the surface and treatment is mostly cosmetic and aimed at dulling any sharp edges. Fractures that expose dentin will have an ivory-yellow appearance. In younger patients, there is less dentin relative to the pulp and treatment is aimed at protecting any pulp contamination with placement of a calcium-hydroxide dressing. Younger patients need more urgent follow-up with a dentist. The most significant dental fractures involve the pulp as in this clinical scenario. The tooth should be gently wiped clean with gauze and inspected for a drop of blood or pink blush which represents pulp exposures. The area is usually exquisitely painful. Timely follow-up (within 24 hours) is required for evaluation and possible root canal and extraction of the pulp. If dental follow-up will be delayed, the tooth should be covered with moist cotton and sealed with dry foil or a temporary commercial sealant. In order to clean the tooth, a clean gauze should be used to wipe off the surface, not irrigation of the tooth (B) as the patient will be extremely sensitive to that and all efforts should be maintained to avoid pulp contamination. Hank’s solution (C) is a physiologic solution in which an avulsed tooth may be placed while waiting for reimplantation into the socket. There is no role in a partial tooth fracture. Viscous lidocaine (D) is not an appropriate analgesic for a dental fracture. Oral analgesics or dental block should be provided for pain control.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References

- Gorchynski J, Karabidian E, Sanchez M. The “syringe” technique: a hands-free approach for the reduction of acute nontraumatic temporomandibular dislocations in the emergency department. The Journal of emergency medicine. 47(6):676-81. 2014. [pubmed]

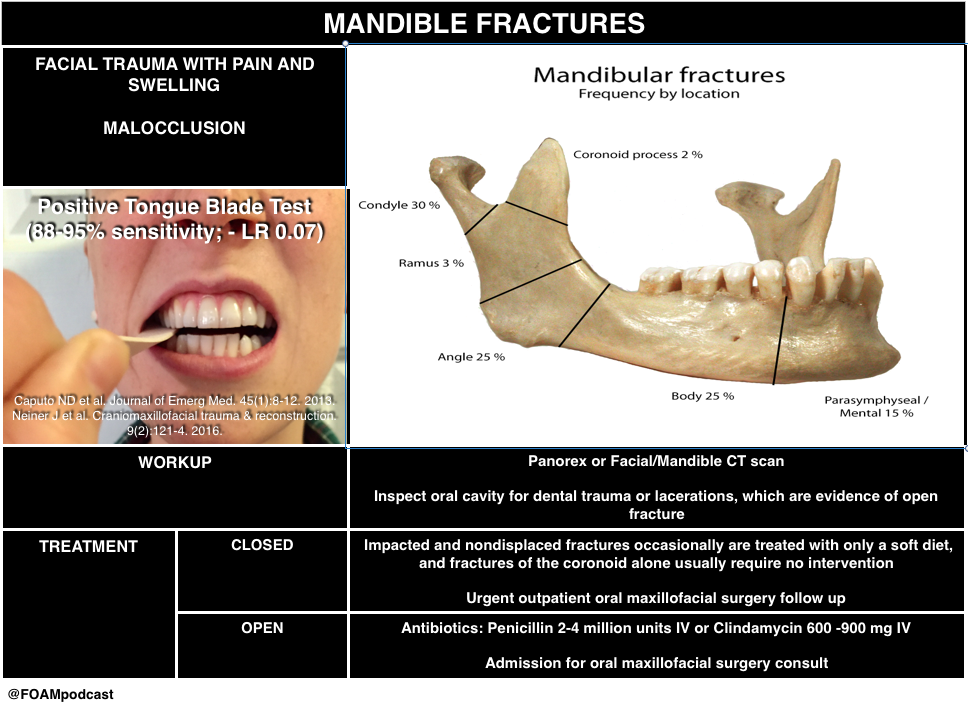

- Caputo ND, Raja A, Shields C, Menke N. Re-evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of the tongue blade test: still useful as a screening tool for mandibular fractures? The Journal of emergency medicine. 45(1):8-12. 2013. [pubmed]

- Neiner J, Free R, Caldito G, Moore-Medlin T, Nathan CA. Tongue Blade Bite Test Predicts Mandible Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 9(2):121-4. 2016. [pubmed]