(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

Life in the Fast Lane Research and Reviews (LITFL R&R) #121 featured a section on the new American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) guidelines on diverticulitis. The game changer? Antibiotics aren’t a requirement in select patients with uncomplicated acute diverticulitis [1].

The guidelines based this recommendation on two studies, previously covered by Dr. Ryan Radecki on Emergency Medicine literature of note over the past 3 years. This post details a prospective observational study on antibiotics for acute diverticulitis [2]. In another post, Dr. Radecki discusses an RCT of antibiotics (ABX) vs IV fluids only.

- 623 patients with an episode with a short history and with clinical signs of diverticulitis, with fever (>38 Celsius) and inflammatory parameters, verified by computed tomography (CT), and without any sign of complications (fistula, perforation, abscess) or signs of sepsis

- Randomized to IVF only or IVF + antibiotics

- Primary Outcome – 6 patients (1.9%) developed complications in the no ABX arm vs 3 patients (1.0%) in the ABX arm (not statistically significant). Overall study complication rate was 1.4% [3].

Of note, since 2012, the Cochrane Review suggests that antibiotics may not be necessary in uncomplicated appendicitis [4].

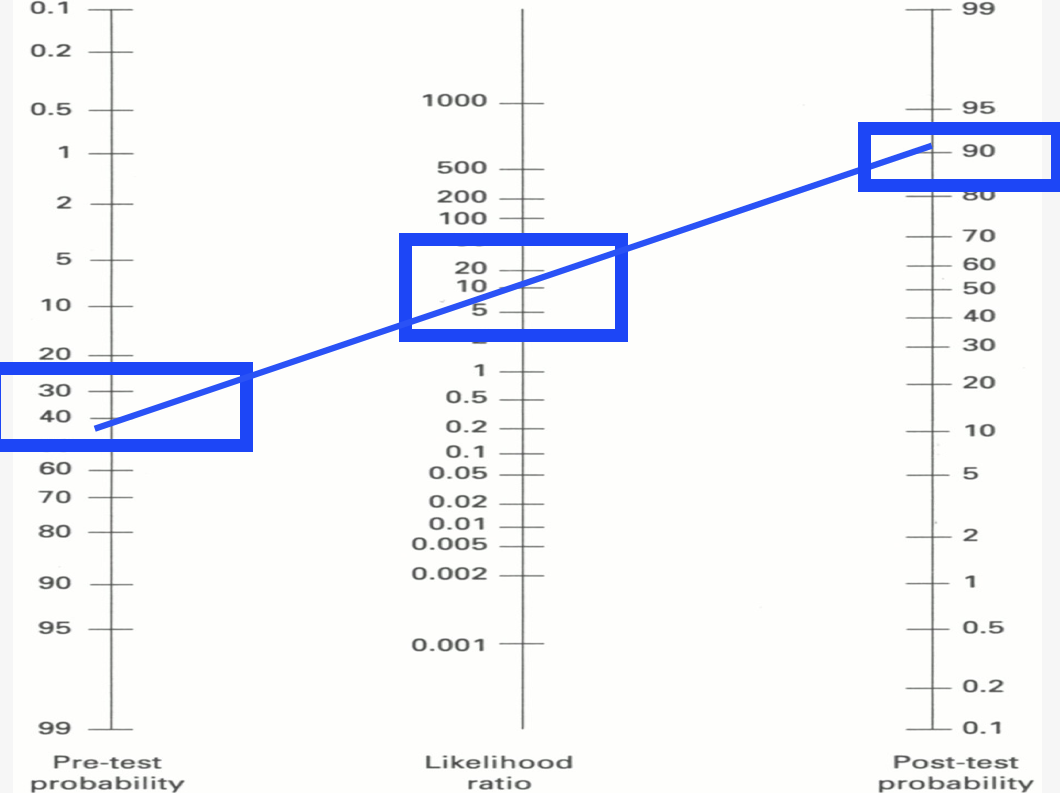

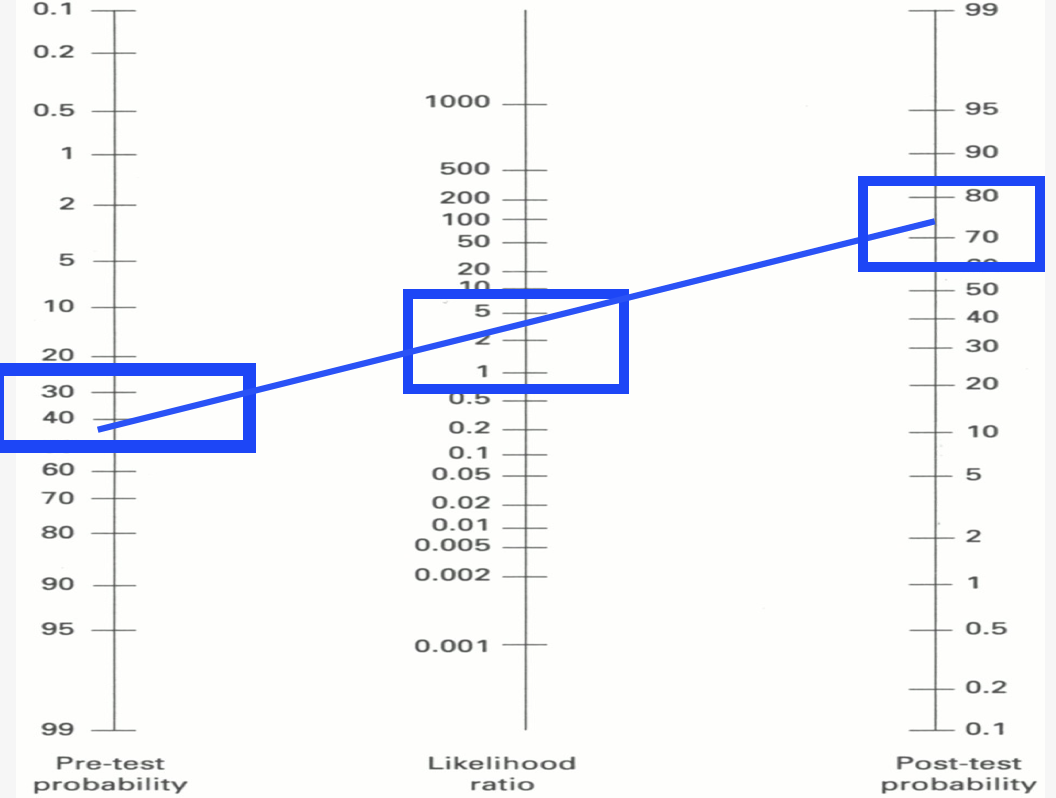

A note on LITFL R&R – every week this blog post features 5-10 high yield articles, culled from contributors across the globe from all kinds of literature – pediatrics, critical care, emergency medicine, etc. It is difficult to keep up with the literature and some have estimated that the number needed to read (NNR) to of 20-200, depending on the journal [5]. Those looking for high yield articles may find their time well spent focused on this cherry picked selection of articles.

Core Content

We delve into core content on diverticula and clostridium difficile using Rosen’s Medicine (8e), Chapters 31, 173 and Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (7e) Chapters 76, 85.

Diverticulosis

Diverticula are small herniations through the wall of the colon (small outpouchings). Often this is asymptomatic, identified incidentally on imaging or colonoscopy. Most common cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) in adults in the U.S.

Diverticulitis

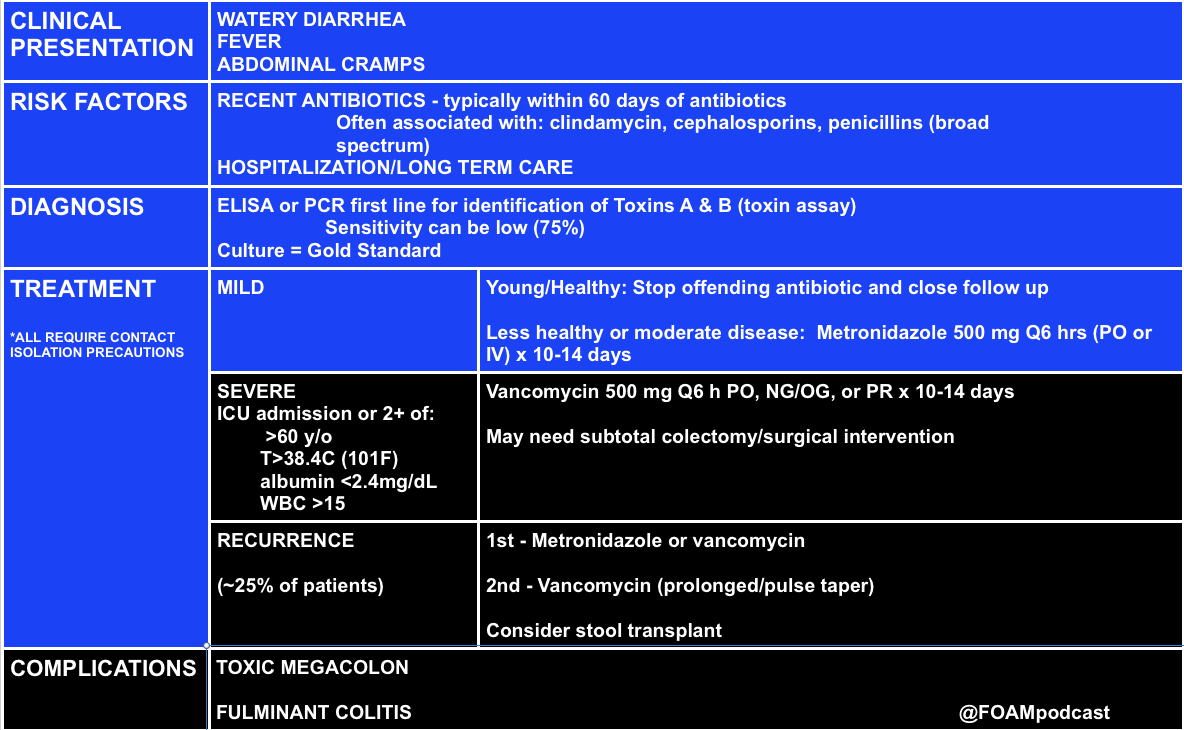

Clostridium Difficile (c. diff)

Note on testing – asymptomatic carriage rates of c.diff vary based on the population but may be between 3-50%. Textbooks quote a 3% carriage rate in newborns and rates of 20%-50% in hospitals and long term care facilities, respectively [10,11].

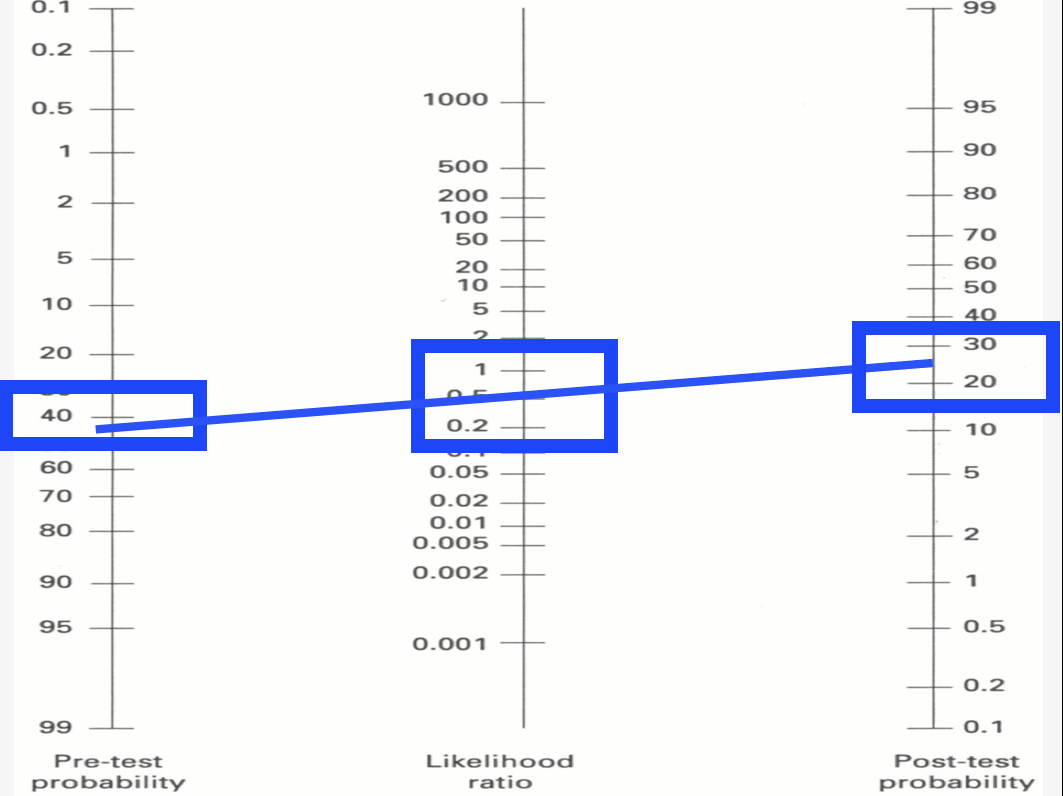

C. diff historically has a unique odor, refrains of “it smells like c. diff” echo in the halls. Yet this does not perform very well, essentially a coin flip based on a 2013 study by Rao and colleagues. They had 18 nurses smell 10 stool samples (5 c. diff positive and 5 c. diff neg) and found the median percent correct identification of c. diff positive vs negative was 45% [6].

Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. [polldaddy poll=9330955]

Question 2.A 75-year-old woman presents with several days of voluminous watery stools. She was discharged from the hospital one week ago following treatment for pneumonia. Stool studies reveal C. difficile toxin. [polldaddy poll=9333580]

Answers:

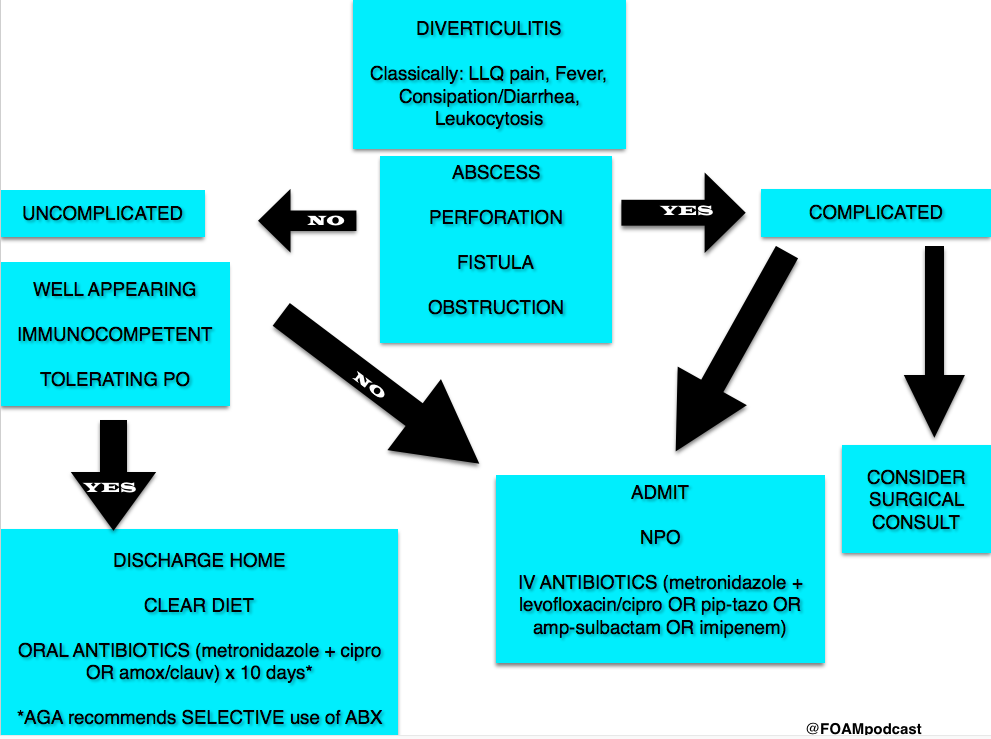

- C. Patients who present with uncomplicated diverticulitis should be treated with oral antibiotics for 7-10 days. Diverticulitis is an inflammation of the diverticulum in the large intestine. In uncomplicated cases of diverticulitis, patients present with abdominal pain typically in the left lower quadrant with tenderness to palpation in the same area. Patients should not have peritoneal signs or masses on examination. Complicated diverticulitis is defined as the presence of either extensive inflammation or complications such as abscess, peritonitis or obstruction. Patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis can be empirically treated with antibiotics (typically as an outpatient) for 7-10 days. Patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis typically do not require CT imaging (A). Patients with complicated diverticulitis should be treated with intravenous antibiotics (B) and admitted to the hospital. Ultrasound (D) has shown promise in diagnosing diverticulitis but CT is the imaging modality of choice.

- C.C. difficile infection is caused by a spore-forming obligate anaerobic bacillus that causes a spectrum of disease ranging from diarrhea to pseudomembranous colitis. C. difficile is the most common cause of infectious diarrhea in hospitalized patients in the United States. Risk factors for infection include broad-spectrum antibiotic use, particularly clindamycin, though other antibiotics have also been implicated. Additional risk factors include prolonged hospitalization, advanced age, and underlying comorbidities. The spectrum of clinical manifestations includes frequent watery stools to a more toxic clinical presentation with profuse stools (up to 20-30 per day), crampy abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis, and hypovolemia. C. difficile colitis should be suspected in patients who develop diarrhea while taking or after recent cessation of antibiotics, or among recently discharged patients who develop diarrhea. Diagnosis is confirmed by identification of C.difficile toxin in the stool. Colonoscopy, while not usually necessary for diagnosis, reveals characteristic yellowish plaques in the intestinal lumen, confirming pseudomembranous colitis. Treatment for C. difficile infection depends on disease severity. Previously healthy patients with very mild symptoms may be managed by cessation of the offending antibiotic and close clinical monitoring. Oral metronidazole, 500 mg po every 6 hours for 10-14 days is the treatment for moderately severe colitis. Severely ill patients should be hospitalized and treated with oral vancomycin, 125 mg po every 6 hours for 10-14 days.

References:

- Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Acute Diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1944–9. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.003.

- Isacson D, Thorisson A, Andreasson K, Nikberg M, Smedh K, Chabok A. Outpatient, non-antibiotic management in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: a prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(9):1229–1234. doi:10.1007/s00384-015-2258-y.

- Chabok A, Phlman L, Hjern F, Haapaniemi S, Smedh K. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99(4):532–539. doi:10.1002/bjs.8688.

- Shabanzadeh DM1, Wille-Jørgensen P.Antibiotics for uncomplicated diverticulitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Nov 14;11:CD009092. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009092.pub2.

- McKibbon KA, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. What do evidence-based secondary journals tell us about the publication of clinically important articles in primary care journals? BMC Med. 2004;2:33.

- Rao K, Berland D, Young C, Walk ST, Newton DW. The Nose Knows Not: Poor Predictive Value of Stool Sample Odor for Detection of Clostridium difficile. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 56(4):615-616. 2012.

- “Chapter 85: Diverticulitis.” Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 7e.New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011. p 578-581.

- “Disorders of the Large Intestine.” Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th e. p 1261-1275.

- “Gastrointestinal Bleeding.” Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th e. p 248-253.

- “Infectious Diarrheal Disease and Dehydration.” Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th ep 2188-2204.

- “Chapter 76: Disorders Presenting Primarily with Diarrhea.” Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 7e.New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011. p 534-535