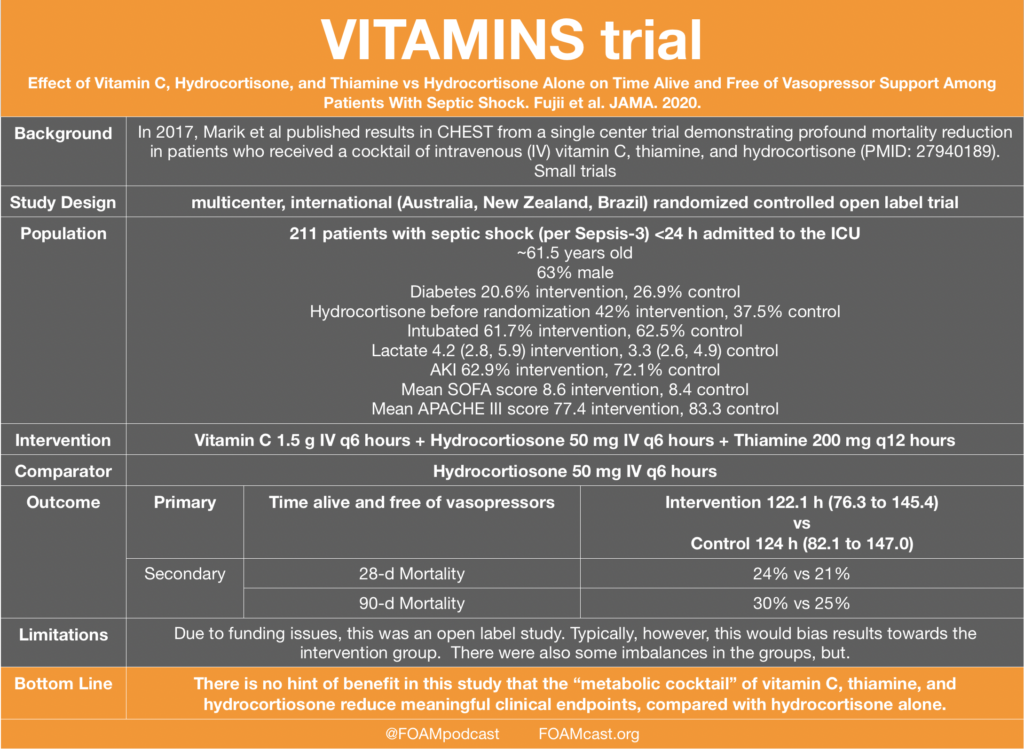

In 2017, Dr. Paul Marik published astonishing results describing one center’s experience implementing the “metabolic cocktail” (Vitamin C 1.5 g q6 hours, hydrocortisone 50 mg q6 hours, thiamine 200 mg q12 hours) in patients with septic shock [1]. News outlets hailed this treatment as a miracle drug. However, this study was a before-and-after single-center study and this trial been discussed elsewhere, including on the Skeptics Guide to Emergency Medicine and Pulmcrit. Essentially all trials have predominantly assessed some variation of length of time on vasopressors as a primary outcome (or one of the primary outcomes), but several have reported on mortality. Now, we have the VITAMINS trial, as detailed below, the first rigorous study to evaluate metabolic resuscitation in a general septic shock population [2].

The authors published their protocol in advance (VITAMINS trial protocol) and appeared to follow it. Despite falling completely flat, this trial may not be sufficient for some individuals to give up belief in this treatment.The VICTAS trial (multicenter blinded RCT in the US) has enrolled ~500 of the 2000 estimated patients (VICTAS trial protocol.).

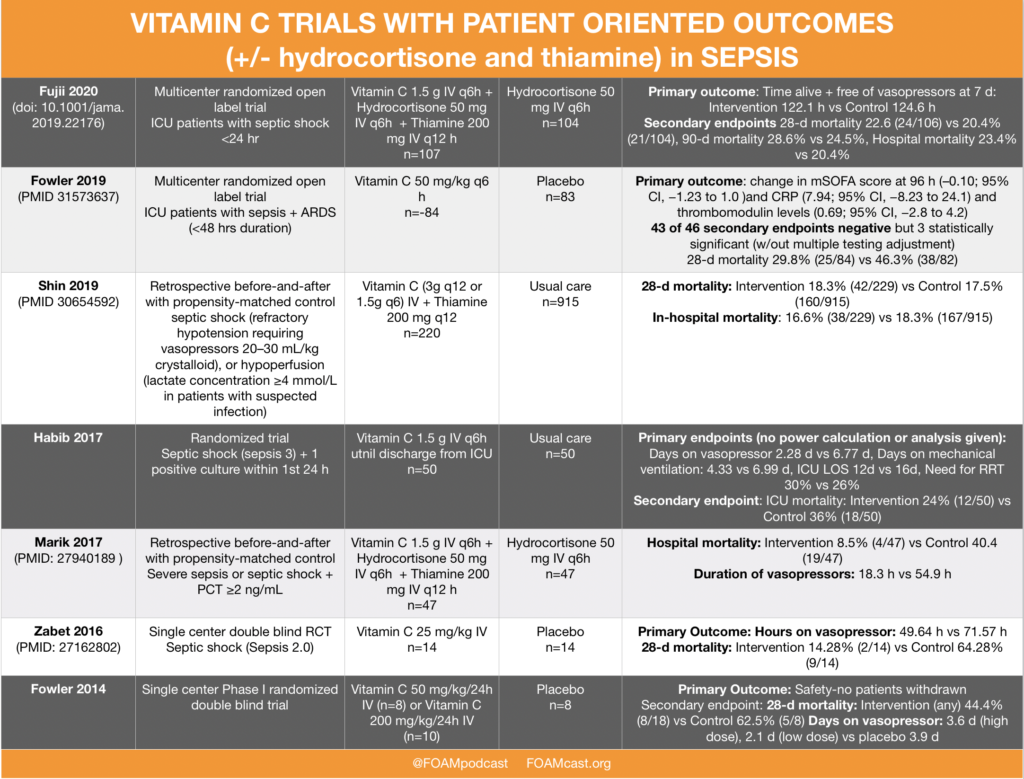

So, how does this compare in the landscape of Vitamin C? See the table below. Many of the historical studies are not RCTs and the ones that are, many these studies have unclear methods sections or significant design limitations, are small, and have discordant results [3-7].

- Marik PE et al. Hydrocortisone, Vitamin C, and Thiamine for the Treatment of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Retrospective Before-After Study. Chest. 2017;151(6):1229-1238.

- Fujii et al. Effect of Vitamin C, Hydrocortisone, and Thiamine vs Hydrocortisone Alone on Time Alive and Free of Vasopressor Support Among Patients With Septic Shock The VITAMINS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020: In Press.

- Fowler et al. Effect of Vitamin C Infusion on Organ Failure and Biomarkers of Inflammation and Vascular Injury in Patients With Sepsis and Severe Acute Respiratory Failure: The CITRIS-ALI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. October 1, 2019.

- Shin TG, Kim YJ, Ryoo SM, et al. Early Vitamin C and Thiamine Administration to Patients with Septic Shock in Emergency Departments: Propensity Score-Based Analysis of a Before-and-After Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2019;8(1)

- Zabet MH, Mohammadi M, Ramezani M, Khalili H. Effect of high-dose Ascorbic acid on vasopressor’s requirement in septic shock. J Res Pharm Pract. 2016;5(2):94-100.

- Habib et al. Early Adjuvant Intravenous Vitamin C Treatment in Septic Shock may Resolve the Vasopressor Dependence. International Journal of Microbiology & Advanced Immunology (IJMAI)j. 2017 05(1), 77-81.

- Fowler AA, Syed AA, Knowlson S, et al. Phase I safety trial of intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with severe sepsis. J Transl Med. 2014;12:32.