(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

We review Dr. Ken Milne’s podcast, The Skeptic’s Guide to Emergency Medicine Episode #89, special episode on falls in the geriatric. This episode is the first in the HOP (Hot Off the Press) series in which Dr. Milne has paired with Academic Emergency Medicine and the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine to review a paper, with the author, the same week the paper is published.

Why HOP is special:

- Reducing the knowledge gap by disseminating hot-off- the press

- Concurrent peer review from global audience. Peer review is a flawed process and in this way, Dr. Milne takes his skeptical perspective to the paper and the author.

- Key comments from social media will then be published in these journals, reaching the traditional academic readership.

Pearls from the Carpenter et al systematic review

Fall Statistics:

- Fall Rates – > 65 y/o – 1 in 3 people fall per year; > 80 years old – 1 in 2 people fall per year

- Elderly patients who fall and are admitted have a 1 year mortality of ~33% [1,3]. So, geriatric falls are bad, it seems logical to wish to predict who is going to fall.

Predictors of Falls:

- The best negative likelihood ratio (-LR) was if the patient could cut their own toenails –LR 0.57 (95% CI 0.38-0.86) (remember, the target for a -LR is 0.1). This outperformed traditional assessments like the “get up and go test.”

- Previous history of falls is a big predictor of falls. Of elderly patients who present to the ED with a fall, the incidence of another fall by 6 months later is 31%. Of those patients who present with a fall as a secondary problem,14% had another fall within 6 months.

- The Carpenter instrument has a promising -LR of 0.11 (95% CI = 0.06-0.20) but has not been validated

- Carpenter instrument: Nonhealing foot sores, self-reported depression, not clipping one’s own toenails, and previous falls

The Bread and Butter

We summarize some key topics from the following readings, Tintinalli (6e) Chapter 307 (This chapter was removed from the seventh edition) ; Rosen’s 8(e) Chapter 182 – but, the point isn’t to just take our word for it. Go enrich your fundamental understanding yourself!

Abdominal Pain Abdominal pain in the elderly is much higher risk than the younger cohort. This is complicated by vague presentations. Abdominal pain in the elderly often causes one to raise an eyebrow and ponder chest pathology such as an atypical presentation of ACS. However, the converse can also be true. Chest discomfort may really reflect intra-abdominal pathology. Bottom line – presentations are vague and badness is common.

Geriatric abdominal pain stats:

- Fever and WBC unreliable. Per Rosen’s “Elders with potentially catastrophic intra-abdominal processes may not present with a fever or an elevated white blood cell count.”

- Much higher risk than younger patients – 2/3 patients admitted and 1/5 go directly to the operating room.

- Most common serious pathologies: Biliary pathology (cholecystitis), small bowel obstruction, appendicitis.

- Vascular pathologies such as abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and mesenteric ischemia also have an important place in the differential given increased incidence in the elderly.

FOAM resources:

Polypharmacy Elderly patients are often on a host of medications but have physiologic alterations that make them susceptible to increased adverse events.

- 12-30% of admitted elderly patients have adverse drug reactions or interactions as a primary or major contributing factor to their admission and 25% of these drug reactions or interactions are serious or life-threaten

- Garfinkel et al demonstrated that reducing medications in elderly nursing home patients may actually be better for their health.

- Some of the highest risk medications, in general, for our elderly patients: diuretics, nonopioid analgesics, hypoglycemics, and anticoagulants. A patient’s presentation (syncope, fall) may be a manifestation of a medication side effect.

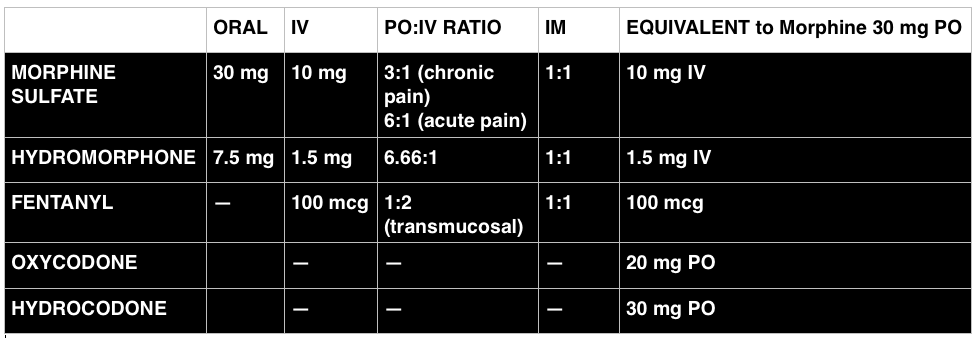

- There are many high risk pharmaceuticals in the ED, but be very cautious of: narcotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, sedative-hypnotics, muscle relaxants, and antihistamines.

- NSAIDS – patients may have reduced renal function and due to loss of lean muscle mass, creatine may not be accurate and NSAIDs may tip the patient into renal insufficiency. These drugs may also worsen hypertension and congestive heart failure as a result of salt retention. NSAIDs are also associated with gastrointestinal bleeding. Be cautious – acetaminophen is the safer bet.

- Narcotics – may predispose patients to falls (which are bad in the elderly). These drugs may also constipate patients, which can cause abdominal pain. Give guidance and make sure the patient has a solid bowel regimen.

- Start low and go slow. It’s much easier to add doses of medications than clearing excess medications.

- Cautiously start new medications. Furthermore, as drugs may be responsible for the patient’s symptoms that brought them to the ED, review the medication list. If possible, consider discussing discontinuation of medications with the patient’s PCP.

FOAM resources:

Delirium – Delirium in the elderly ED patients is associated with a 12-month mortality rate of 10% to 26% [5]. Be wary of chalking up alterations in mental status to dementia or sundowning.

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions (Scroll for Answers)

Question 1. [polldaddy poll=8443367]

Question 1. An 87-year-old woman presents to the ED after her caregiver witnessed the patient having difficulty swallowing over the past 2 days. The patient is having difficulty with both solids and liquids. She requires multiple swallowing attempts and occasionally has a mild choking episode. She has no other complaints. Your exam is unremarkable. [polldaddy poll=8443380]

Bonus Question: What proportion of elderly patients with proven bacterial infections lack a fever?

References:

1.Carpenter CR, Avidan MS, Wildes T, et al. Predicting Geriatric Falls Following an Episode of Emergency Department Care: A Systematic Review. Acad Emerg Med. 2014 Oct;21(10):1069-1082.

2. “The Elder Patient.” Chapter 182. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8e.

3. “The Elderly Patient.” Chapter 307. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Review, 6e.

4. Garfinkel D1, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007 Jun;9(6):430-4.

5. Gower LE, Gatewood MO, Kang CS. Emergency Department Management of Delirium in the Elderly. West J Emerg Med. May 2012; 13(2): 194–201.

Answers:

1.D. Physiologic changes of aging affect virtually every organ system and have many effects on the health and functional status of the elderly. Compared to healthy adults, elderly patients have a decreased thirst response that puts them atincreased risk for dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities. Cell-mediated immunity (A) is decreased, which increases susceptibility to neoplasms and a tendency to reactivate latent diseases. Peripheral vascular resistance (B) is increased contributing to development of hypertension. Sweat glands (C) are decreased in the elderly, which puts them at risk for hyperthermia.

2.B. Dysphagia can be divided into two categories: transfer and transport. Transfer dysphagia occurs early in swallowing and is often described by the patient as difficulty with initiation of swallowing. Transport dysphagia occurs due to impaired movement of the bolus down the esophagus and through the lower sphincter. This patient is experiencing a transfer dysphagia. This condition is most commonly due to neuromuscular disorders that result in misdirection of the food bolus and requires repeated swallowing attempts. A cerebrovascular accident (stroke) that causes muscleweakness of the oropharyngeal muscles is frequently the underlying cause.

Achalasia (A) is the most common motility disorder producing dysphagia. It is typically seen in patients between 20 and 40 years of age and is associated with esophageal spasm, chest pain, and odynophagia. Esophageal neoplasm (C)usually leads to dysphagia over a period of months and progresses from symptoms with solids to liquids. It is also associated with weight loss and bleeding. Foreign bodies (D) such as a food bolus can lead to dysphagia, but patients are typically unable to tolerate secretions and are often observed drooling. These patients do not have difficulty in initiating swallowing.

Bonus. Up to one half.