(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

The Skeptic’s Guide to Emergency Medicine Episode 144, “That Smell of Isopropyl Alcohol for Nausea in the Emergency Department.” This podcast reviews an article by Beadle et al, an RCT on the use of inhalational isopropyl alcohol for nausea.

Population – Adults in the Emergency Department

Intervention – Nasal inhalation of an isopropyl alcohol pad for ~ 60 seconds (time 0 and, if still nauseated, at 2 minutes and 4 minutes)

Comparison – Nasal inhalation of an identical pad soaked in saline.

Outcome -Nausea score at 10 minutes post treatment using an 11-point verbal numeric response scale (0:“no nausea”; 10:“worst nausea imaginable”)

- Lower in the isopropyl group (Median score of 3 vs. 6 on an 11 point scale, p<0.001). This gave an effect size of 3 (95% CI 2 to 4).

Limitations – single center, convenience sample, unclear blinding as isopropyl likely has a particular smell to it, outcome nausea score, not vomiting

Eagerton-Warburton et al conducted an RCT of intravenous ondansetron 4mg, metoclopramide 20mg, or saline (placebo) of adult patients with nausea and found no significant difference in nausea scores on a visual analog scale between groups (n=270).

Core Content

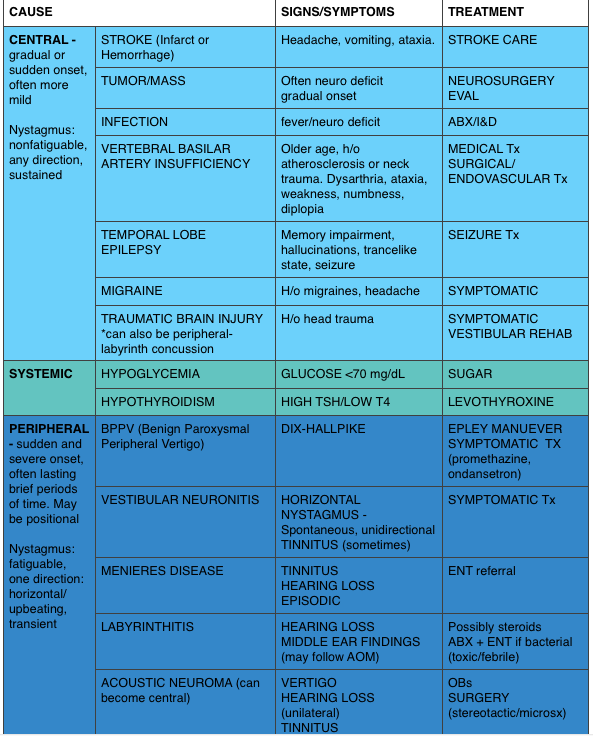

We delve into core content on vertigo using Rosen’s Medicine (8e), Chapter 155 “Toxic Alcohols” and Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (7e) Chapter 179“Alcohols.”

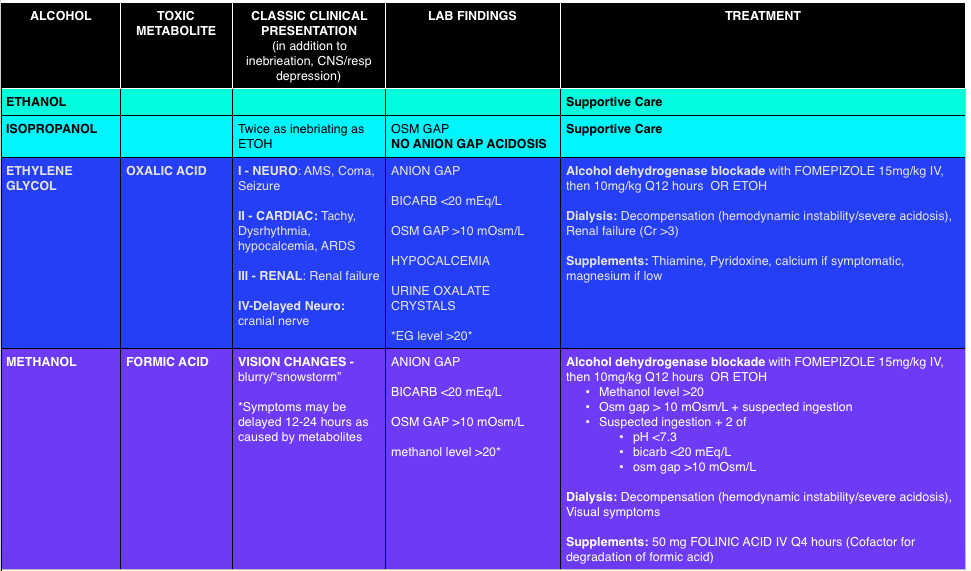

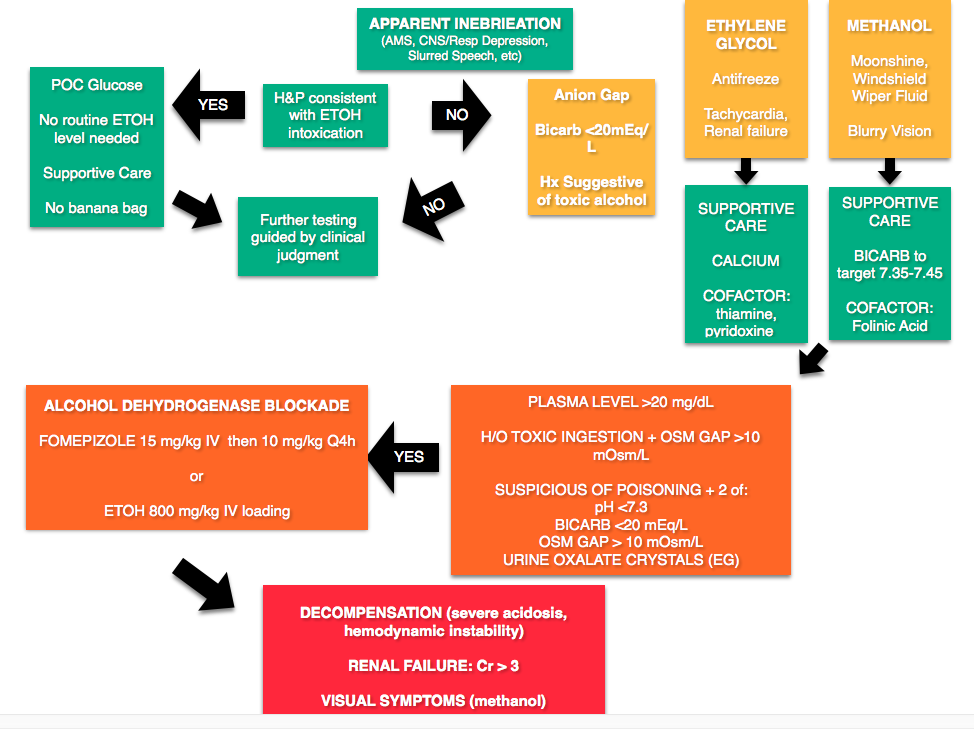

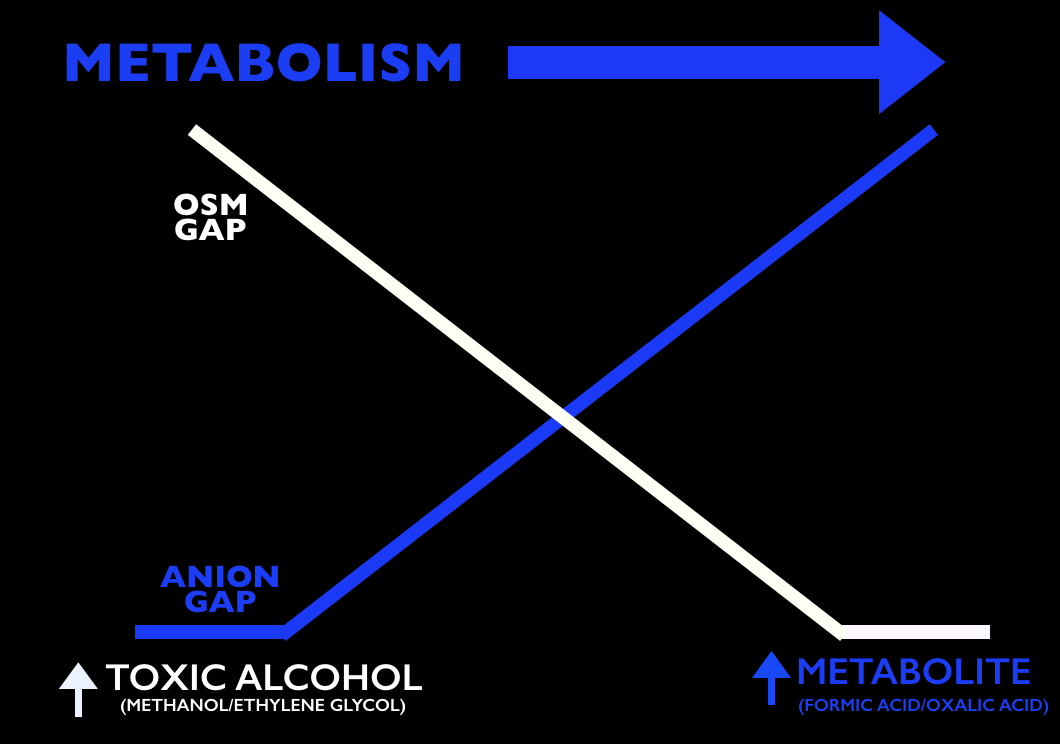

Any alcohol can be “toxic,” the ramifications depend on the dose. Toxic alcohols typically refer to ethylene glycol (EG) and methanol. In these cases, the parent compound (EG or methanol) is inebriating but not particularly toxic. These compounds are metabolized, like any alcohol, but unfortunately the metabolites (oxalic acid – EG, formic acid – methanol) have unique toxic properties. For example, the oxalic acid produced from EG metabolism combines with calcium. These deposit into tissues causing renal failure and neurologic sympotms. The formic acid has a predilection for the retina, causing visual symptoms.

Toxic Alcohols

Osmolal Gap (calculator) – One of the touted features of toxic alcohols is the elevated anion gap, that is, the difference between the measured serum osmolality and the calculated osmolarity.

Calculated Osmolarity: 2[Sodium] + [Glucose]/18 + [BUN]/2.8 + [ETOH]/4.6 (Note: Some references use ETOH/3.7)

- Problems: A normal osm gap does not exclude the presence of toxic alcohols as the osm gap decreases as the alcohol is metabolized. Also, other disease processes can increase the osm gap, including shock, diabetic ketoacidosis, etc [2,3].

A common pearl exists that urine can be placed under a Wood’s lamp for fluorescence due to the fluorescein in ethylene glycol antifreeze (to detect leaks). Unfortunately this is neither sensitive nor specific [4,5].

Treatment

Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. [polldaddy poll=9311166]

Question 2. [polldaddy poll=9311159]

Answers

1. A. Hypocalcemia. Most laboratories do not have the capability to measure serum levels of toxic alcohols in a timely fashion. As a result, physicians must use other clinical markers to determine the presence of these unmeasured toxins. The classic laboratory abnormality is an elevated serum osmolality with an osmolar gap since the actual toxic alcohol is not measured in its own quantity but contributes to the osmolality of the blood. When calculating the osmolar gap, it is important to have a measured serum ethanol level as this is a large contributor to the final osmolality.Ethylene glycol ingestion leads to the formation of calcium oxalate crystals. As a result, serum calcium levels will decrease and hypocalcemia is a surrogate marker for ethylene glycol toxicity.Hypoglycemia (B) is not characteristic of a toxic alcohol ingestion. Hypoglycemia is often seen in chronic alcoholics due to poor nutritional intake. In children, ethanol may induce hypoglycemia. Other toxic ingestions which may lead to hypoglycemia include beta-blockers, sulfonylureas and insulin. Hypokalemia (C) is not associated with any toxic alcohol ingestions. As patients become more acidemic from alcohol ingestions, hyperkalemia may develop. Hyponatremia (D) is not associated with toxic alcohol ingestions. Evidence of hyponatremia on laboratory analysis should prompt further investigation for other underlying causes.

2.C. Glycolic acid level greater than 8 mmol/L. A glycolic acid level greater than 8 mmol/L is an indication for emergent hemodialysis following an acute ethylene glycol overdose. Ethylene glycol is found in automobile coolants, antifreeze, hydraulic brake fluid, de-icing agents and industrial solvents. Symptoms progress through 4 stages: inebriation and intoxication, cardiopulmonary symptoms (tachycardia, hypertension, pulmonary edema), renal symptoms (acute renal failure), and delayed neurologic symptoms (cranial neuropathy). Treatment includes 1.) Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) enzyme blockade with fomepizole or ethanol to prevent toxic and acidic metabolite production, 2.) Correction of the metabolic acidosis with sodium bicarbonate, and 3.) Hemodialysis for removal of the parent compound and toxic metabolites. Although somewhat controversial with the advent of fomepizole other indications for hemodialysis following ethylene glycol ingestion include severe metabolic acidosis, renal failure, deterioration despite intensive care, and electrolyte disturbances.Other indications for emergent hemodialysis following an acute ethylene glycol overdose include: ethylene glycol level greater than 50 mg/dL (B), anion gap greater than 20 mmol/L (A)and initial pH less than 7.3 (D).

References

- Beadle KL, Helbling AR, Love SL, April MD, Hunter CJ. Isopropyl Alcohol Nasal Inhalation for Nausea in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of emergency medicine. 2015. [pubmed]

- Chapter 155. “Toxic Alcohols. ” In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 8th e.

- Chapter 179. Alcohols. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Cline DM, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD, T. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 7e.New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

- Tobe TJM, Braam GB, Meulenbelt J, et al: Ethylene glycol poisoning mimicking Snow White. Lancet 2002; 359: pp. 444

- Wallace KL, Suchard JR, Curry SC, et al: Diagnostic use of physicians’ detection of urine fluorescence in a simulated ingestion of sodium fluorescein–containing antifreeze. Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38: pp. 49