(ITUNES OR LISTEN HERE)

The Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM)

We review the post by Bryan Hayes, PharmD, FAACT on Academic Life in Emergency Medicine, Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim for Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 1 or 2 Tablets BID?

The Take Home: Most abscesses do not need antibiotics after incision and drainage. If the patient has systemic signs (fever, tachycardia), co-morbidities, or a concurrent cellulitis, they may need antibiotics. Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMX-TMP / Bactrim) is one of the most commonly used agents in this case, as it covers MRSA.

Dosing: Two double strength (DS) tablets twice daily is a commonly prescribed regimen; yet,1 DS tablet twice daily is sufficient in most cases with exceptions for patients >100 kg, immunocompromised, or in trauma [1]. ; however, this increases the likelihood of adverse events (nausea, hyperkalemia) without notable substantial positive return.

The Bread and Butter

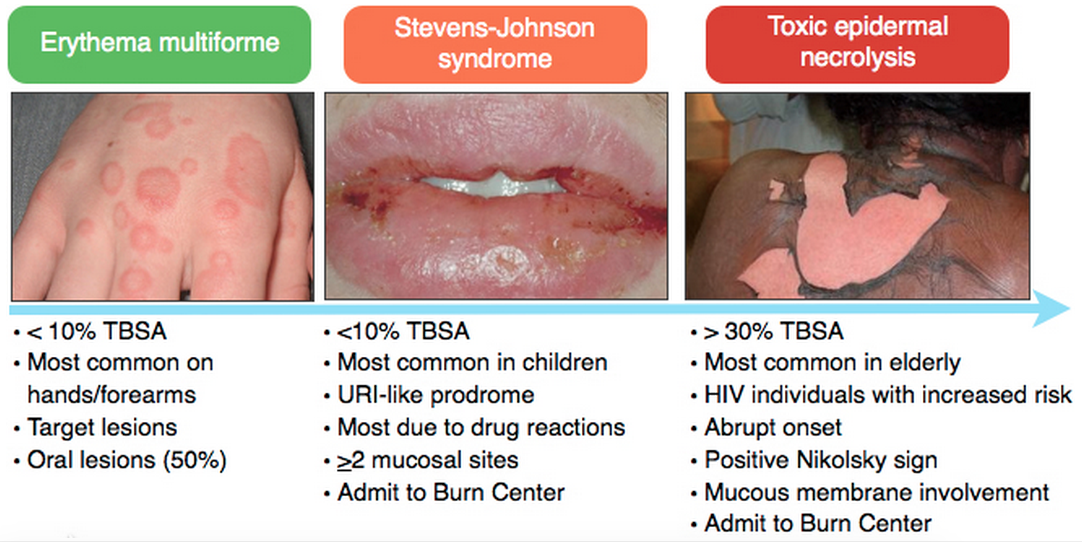

We cover cellulitis and abscesses, necrotizing infections, and Erythema Multiforme/Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal necrolysis using Tintinalli (7e) Chapter; Rosen’s (8e) Chapter 137 as well as the IDSA guidelines. But, don’t just take our word for it. Go enrich your fundamental understanding yourself.

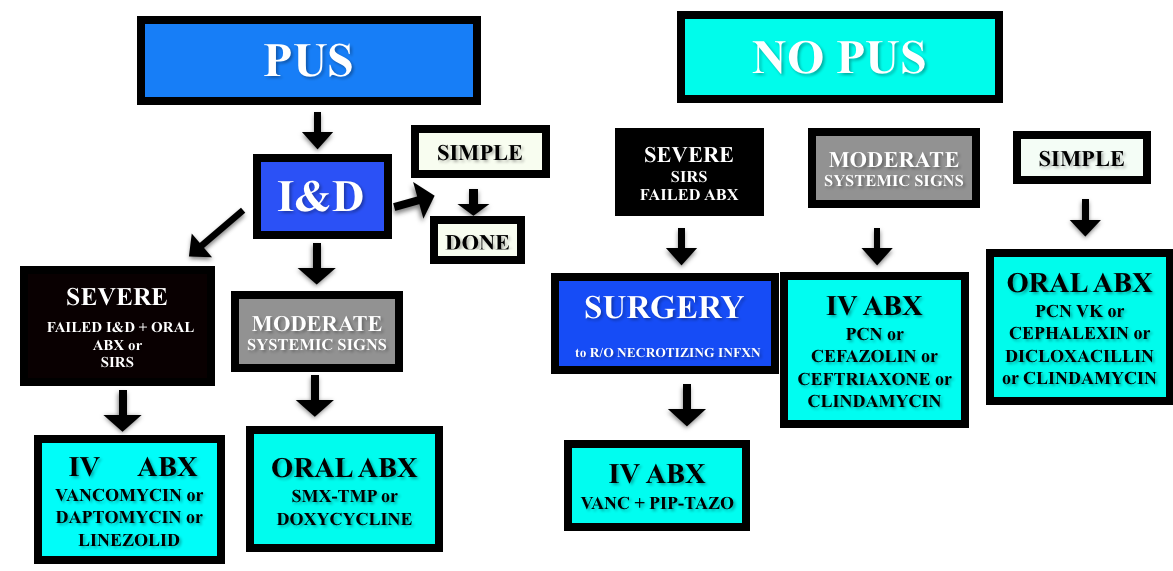

Cellulitis/Abscess

Non-purulent – cover for strep (penicillin, cephalexin/cefazolin). Even in areas with high incidences of community MRSA, the recommendations for non-purulent skin infections is strep coverage. Five days of treatment is probably enough, and IDSA and Rosenalli approved (see this post)

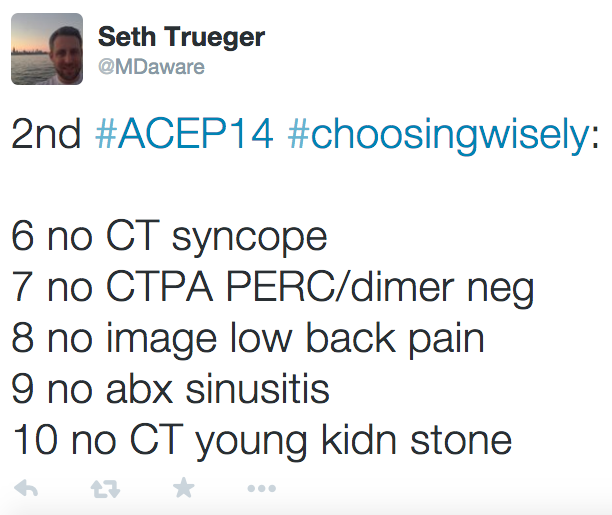

Purulent – Incise & Drain (I&D). Cover for MRSA in patients that failed initial I&D or those with systemic signs.

Necrotizing Infections

Presentation – pain out of proportion to exam findings, abnormal tachycardia (particularly out of proportion to degree of fever). Crepitus is not reliable (present in 13-30% of patients).

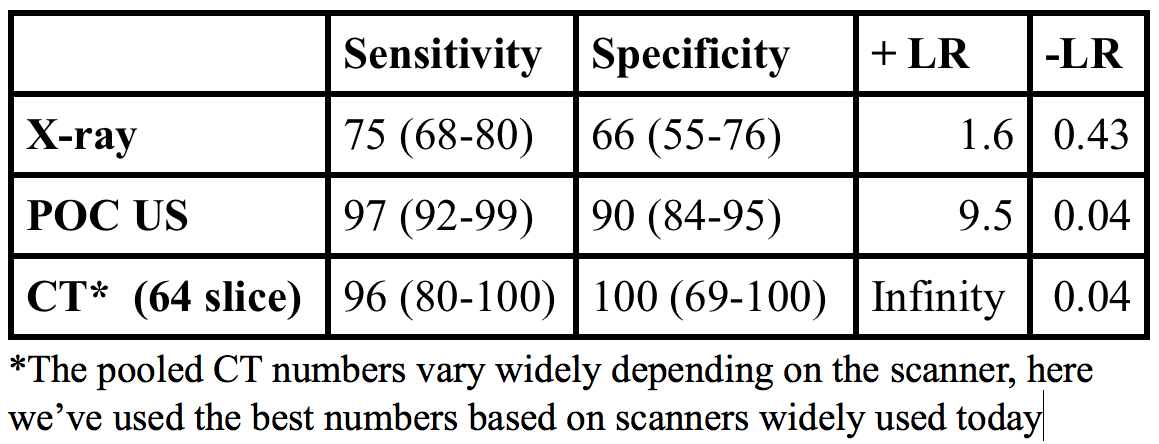

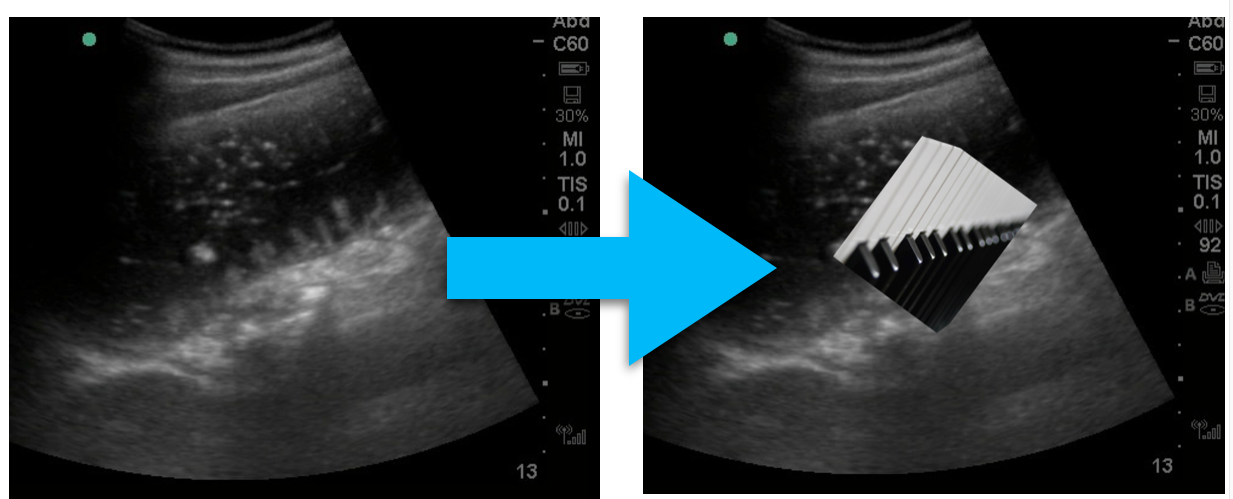

Diagnosis – clinical. X-rays, CT, and MRI have all been used but both x-rays and CT lack sensitivity and it’s probably not a good idea to send a sick patient to MRI. The gold standard diagnosis is operative findings.

- The LRINEC score was derived to aid in diagnosis using lab values (sodium, creatinine, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, glucose, CRP) but has not been sufficiently predictive in validation attempts [10].

Classification

- Type I – polymicrobial. Common in diabetics, immunocompromised.

- Type II – monomicrobial (often Group A strep or clostridia).

- Type III? – vibrio, but apparently this is controversial.

Treatment

- Intravenous fluid and general resuscitation, surgical consult, and antibiotics.

Erythema Multiforme/Stevens-Johnson/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (for more, see this Hippo EM podcast)

Medications most associated with SJS/TEN: Antibiotics (sulfa), Anti-epileptics, Nonsteroidals

Treatment of SJS/TEN: Fluid resuscitation, Burn Center/ICU care, and IVIG

Generously Donated Rosh Review Questions

Question 1. A 22-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with a painful rash. She has had several days of malaise, arthralgias, and low-grade fever, and today developed diffuse painful erythema across her body which is beginning to blister. She takes no medications, but reports completing a course of trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole one week ago for a urinary tract infection. Examination reveals diffuse tender erythema over her trunk and extremities with multiple ill-defined large bullae, some of which have ruptured, leaving large areas of denuded skin behind. Oral ulcerations are also noted. [polldaddy poll=8689023]

Question 2. A 54-year-old man with diabetes presents with severe leg pain. The pain has worsened over the last two days with increased swelling of the calf. He has no chest pain or shortness of breath. Vital signs are: T 101.8°F, BP 98/62, HR 118, RR 18. Physical examination is notable for erythema of the calf, mild tenderness, and crepitus. You initiate IV fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics. [polldaddy poll=8689082]

Answers

1. This patient has toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). TEN is an acute inflammatory process characterized by tender erythema, painful bullae formation, and subsequent exfoliation. It often begins with prodromal symptoms such as fever, malaise, and myalgias. TEN is considered a dermatologic emergency and patients may appear toxic on presentation. Medications (within the first few months of administration) are the most common cause, with sulfa and penicillin antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and oxicam non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs commonly implicated. Management of TEN involves admission to a burn unit, fluid resuscitation, and prevention of secondary infection. Steroids are not an indicated treatment. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (C) occurs primarily in infants and young children. Infection with exotoxin-producing Staphyloccus aureus leads to diffuse erythroderma and subsequent exfoliation. Mucous membranes are not usually involved. Treatment is fluid resuscitation and antibiotics. Infection with HSV-1 and HSV-2 results in localized skin infection, though in patients with underlying immunosuppression or malignancy it may lead to disseminated herpes simplex virus infection (A), characterized by diffuse vesicles and ulcerations and multisystem involvement. Photosensitive drug reactions (B) are characterized by confluent erythema, macules, papules, or sometimes vesicles in sun-exposed areas such as the face, neck, and arms, occurring within 1-3 weeks of the patient taking an offending agent. Medications commonly associated with photosensitivity include sulfonamides, thiazides, furosemide, and fluoroquinolones

2. Necrotizing fasciitis is an infection of the subcutaneous tissue that spreads rapidly across the fascial planes and is often fatal even with aggressive treatment. Risk factors for necrotizing infections include diabetes, vascular insufficiency, and immunosuppression. Classically patients have pain out of proportion to examination. Later findings include diffuse swelling, erythema, induration and crepitus. The gold standard for diagnosis is direct visualization in the operating room by a surgeon. Surgeons may elect to perform a bedside biopsy prior to full exploration. Management includes aggressive IV hydration, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and surgical debridement. CT scan with intravenous contrast of the lower extremity (A) may demonstrate findings suggestive of a necrotizing infection including subcutaneous gas, stranding along the fascial planes or fluid collection. However, the negative predictive value of CT scan has not been quantified and is not yet considered the gold standard. Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremity (B) may be helpful in identifying venous thrombosis as a cause of edema and fullness of the leg. Additionally, sonography may visualize an area of deep fluid collection and may demonstrate artifact from a significant amount of subcutaneous air if present. Measurement of serum lactate and CPK (C) is helpful when positive but not sensitive enough to rule out the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) incorporates other laboratory markers (CRP, WBC, Hemoglobin, Sodium, Creatinine, Glucose) into a decision-rule however lacks sufficient sensitivity in larger studies.

References

1.Stevens DL, Bisno a. L, Chambers HF, et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014.

2. Shehab N1, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Sep 15;47(6):735-43.

3. Bourgois FT, Mandl KD, Valim C et al. Pediatric Adverse Drug Events in the Outpatient Setting: An 11-Year National Analysis. Pediatrics. Oct 2009; 124(4): e744–e750.

4. Goldman JL, Jackson MA, Herigon JC et al. Trends in Adverse Reactions to Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole. Pediatrics. Jan 2013; 131(1): e103–e108.

5. Khow KS, Yong TY. Hyponatraemia associated with trimethoprim use. Curr Drug Saf. 2014;9:(1)79-82. [pubmed]

6.Antoniou T, Hollands S, Macdonald EM, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and risk of sudden death among patients taking spironolactone. CMAJ. 2015.

7. Hepburn MJ, et al. Comparison of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days) treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Intern med 2004; 164, 1669-1674

8. Hurley HJ, Knepper BC, Price CS, et al. Avoidable antibiotic exposure for uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections in the ambulatory care setting. Am J Med. 2013;126(12):1099–106.

9. Pallin DJ, Binder WD, Allen MB et al. Clinical Trial: Comparative Effectiveness of Cephalexin Plus Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole Versus Cephalexin Alone for Treatment of Uncomplicated Cellulitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. (2013) 56 (12): 1754-1762.

10.Liao CI, Lee YK, Su YC et al. Validation of the laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) score for early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Tzu Chi Medical Journal (2012) 24(2):73-76

Indomethacin (B) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent commonly used in the treatment of acute gout. Gout is an arthritis caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the joint space. Acute flares involve a monoarticular arthritis with a red, hot, swollen and tender joint. Acute episodes of gout result from overproduction or decreased secretion of uric acid. However, measurement of serum uric acid (C) does not correlate with the presence of absence of an acute flare. A radiograph of the knee (D) may show chronic degenerative changes associated with gout but will not help to differentiate a gouty arthritis versus septic arthritis.

Indomethacin (B) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent commonly used in the treatment of acute gout. Gout is an arthritis caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the joint space. Acute flares involve a monoarticular arthritis with a red, hot, swollen and tender joint. Acute episodes of gout result from overproduction or decreased secretion of uric acid. However, measurement of serum uric acid (C) does not correlate with the presence of absence of an acute flare. A radiograph of the knee (D) may show chronic degenerative changes associated with gout but will not help to differentiate a gouty arthritis versus septic arthritis.