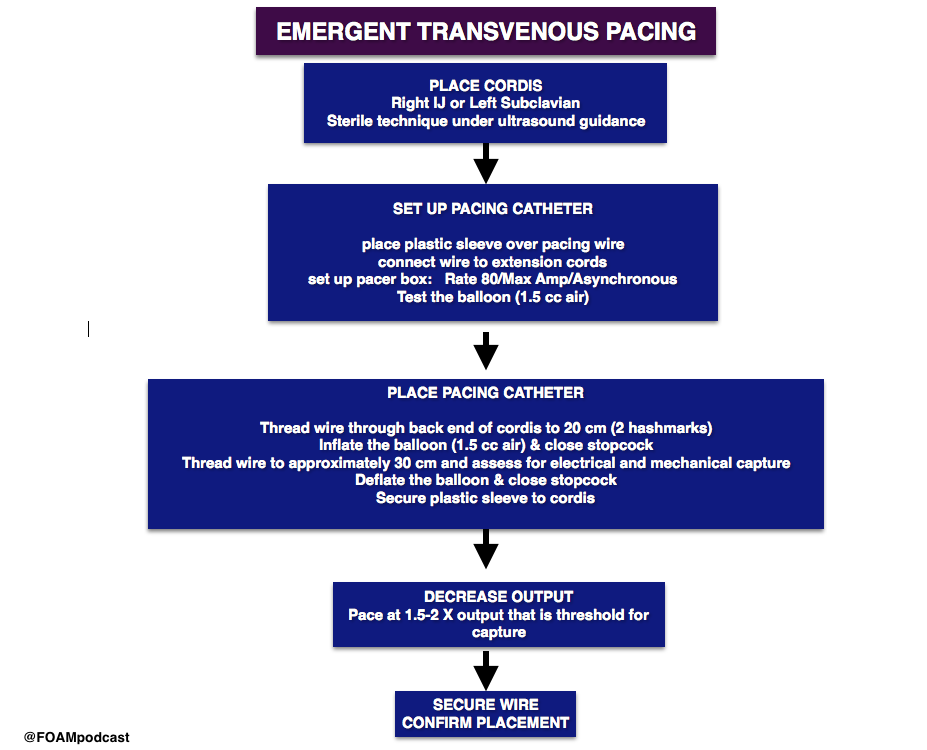

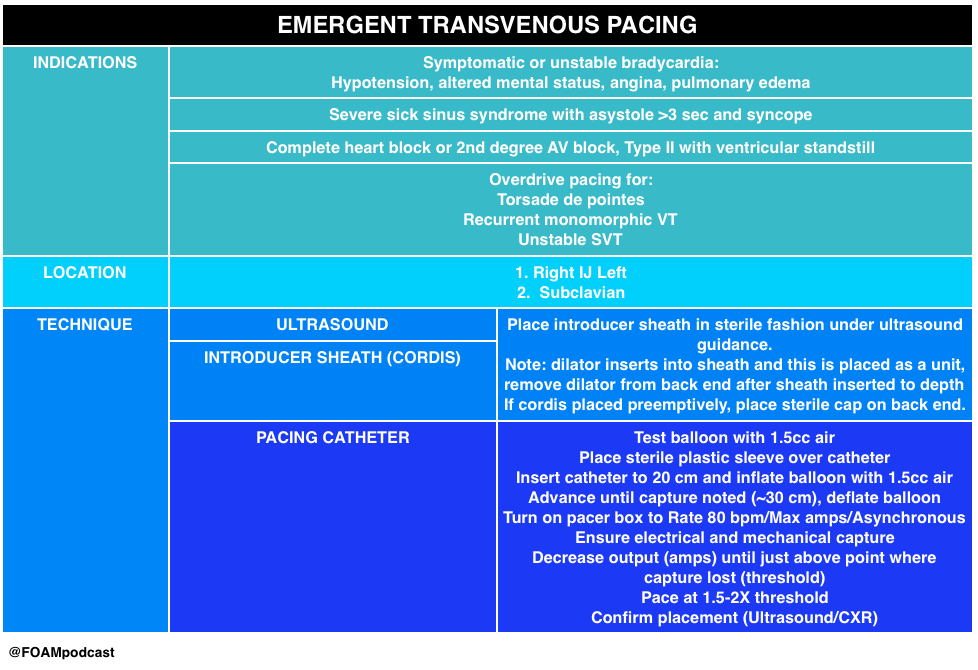

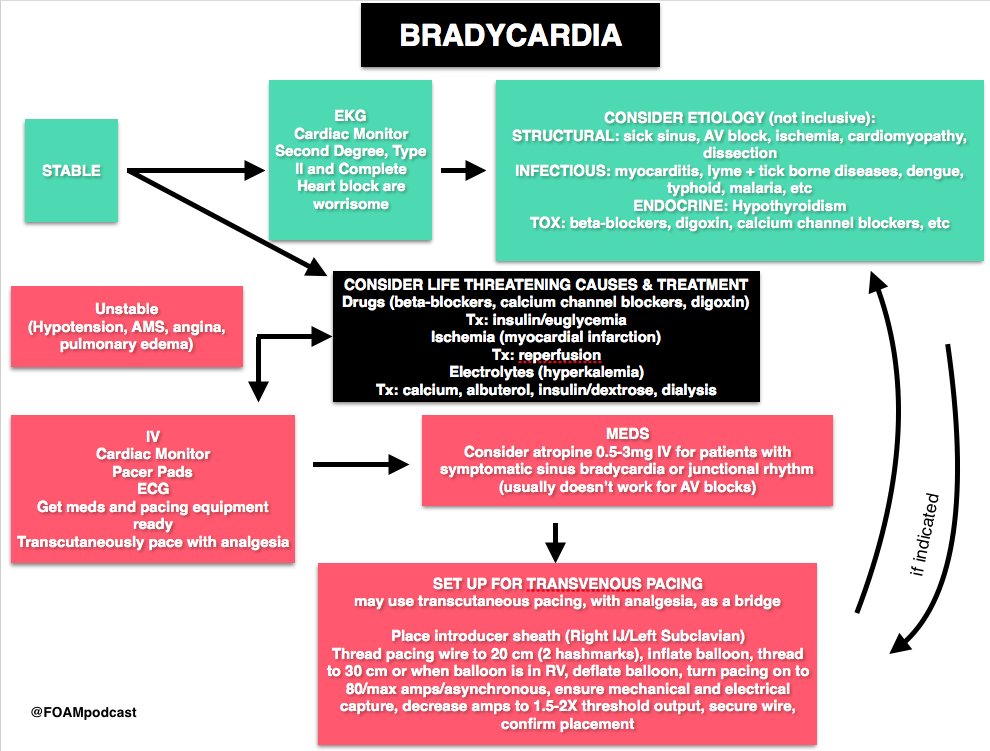

Emergent transvenous pacing is a crucial skill for emergency physicians. It may be daunting due to the pacing box and various catheters. We have found that routinely rehearsing the procedure, reviewing where pacing equipment is in our departments, and where

In this episode we review the following videos:

- Practical Pointers for Pacemaker Placement by Dr. Jason Nomura

- Transvenous pacing video by Dr. Al Sachetti

- Pacing 101 (Transcutaneous is Just Stupid) by Dr. Joe Bellezo on the Ultrasound Podcast

- This podcast lays down the argument that transcutaneous pacing is stupid. Transcutaneous pacing is difficult – patients are diaphoretic, capture rates may be 40%, and it takes a significant amount of energy. Further, it hurts.

- However, in our opinion, there may be a role. In this talk, Dr. Bellezo quotes a 1981 study, in which emergent pacers were placed in “6 minutes.” Review of this study finds that this was actually 6 minutes, 45 seconds (closer to 7 minutes) [1]. This likely does not reflect the majority of emergency providers experience, certainly not ours, where the range is more often 15-30 minutes for the procedure. Thus, transcutaneous pacing may be a temporizing measure as one locates the ultrasound, gathers the supplies, and prepares for transvenous pacing in the unstable patient.

- This podcast lays down the argument that transcutaneous pacing is stupid. Transcutaneous pacing is difficult – patients are diaphoretic, capture rates may be 40%, and it takes a significant amount of energy. Further, it hurts.

Core Content

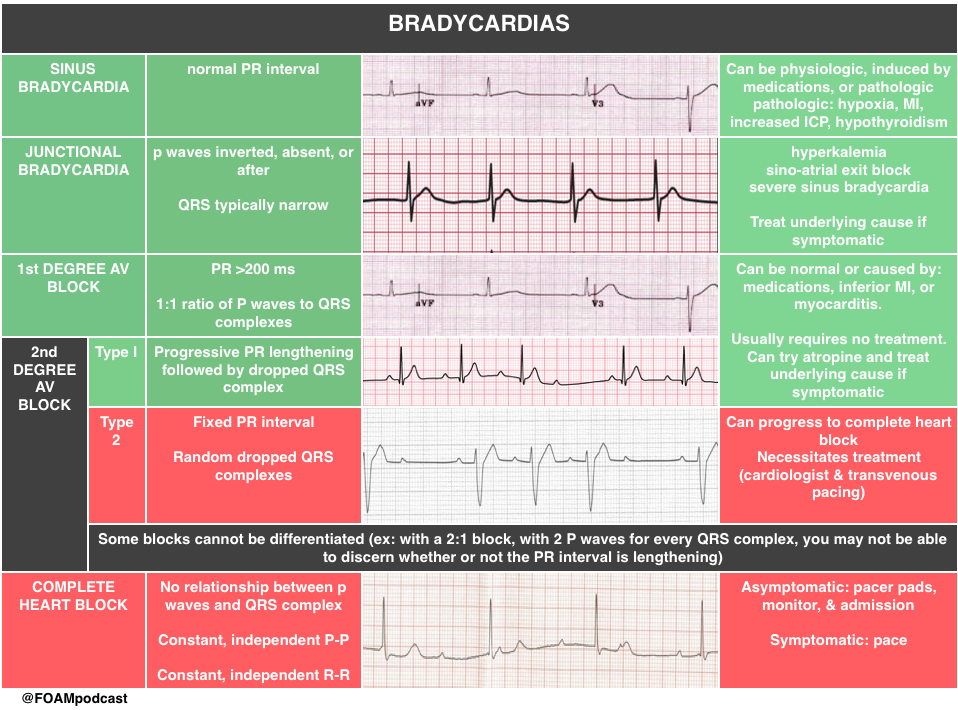

We delve into core content on bradycardias and heart blocks using Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) Chapter 79 “Dysrthymias” and Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine (8th edition) Chapter 18 “Cardiac Rhythm Disturbances” as a guide.

Rosh Review Emergency Board Review Questions

Question 1a.

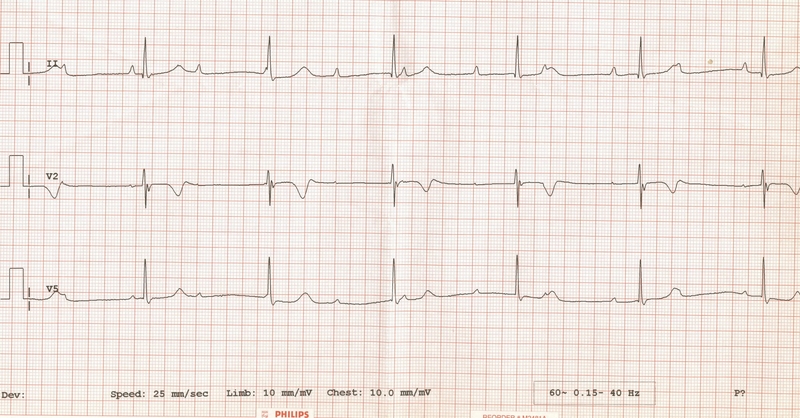

A 71-year-old woman presents after a fall at home. Her electrocardiogram is shown below.

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

Third Degree Heart block.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Question 2.

A. Administration of epinephrine

B. Defibrillation

C. Observation

- D. Placement of transcutaneous pacer pads

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

D. The patient has third degree heart block. In third degree atrioventricular (AV) block, also known as complete heart block, there is no conduction through the AV node, and an escape pacemaker is responsible for the ventricular rate. On electrocardiogram, P waves occur at regular intervals, and QRS complexes occur at regular intervals, but there is no association between the P waves and QRS complexes. When the block occurs in the AV node, a junctional escape pacemaker takes over with a rate of 40-60 beats/minute, and the QRS complex is narrow. If the block occurs at the infranodal level, a ventricular escape pacemaker paces at a rate of 40 beats/minute or less. Infranodal blocks results in a wide QRS complex. Patients with third degree heart block require cardiac pacing, as the slow escape rhythm is rarely adequate to maintain cardiac output and tissue perfusion. Transcutaneous pacing should be initiated while arrangements for transvenous pacing are made. Third degree blocks are commonly associated with cardiac ischemia or infarction. A nodal third degree block (narrow QRS complex) is a complication of acute inferior wall myocardial infarction, and may last for several days. Extensive acute anterior wall infarction is associated with infranodal third degree blocks (wide complex QRS), indicating damage to the infranodal conduction system. When a third degree heart block is seen with acute myocardial infarction, mortality is increased.

Administration of epinephrine (A) is incorrect. Defibrillation (B) the treatment for cardiac arrest from ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. Observation (C) is incorrect since the patient’s slow heart rate is likely not adequate to maintain cardiac output.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Question 3.

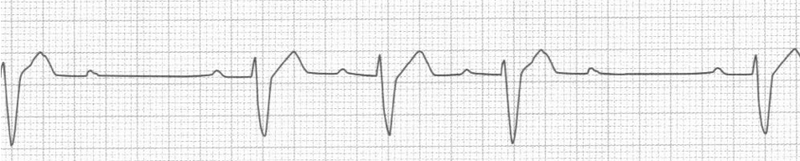

A 56-year-man presents to the ED with right arm pain and some chest discomfort. The day prior to arrival, he tried using heavier weights at the gym. He has a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and COPD. In the ED, his vital signs are BP 136/90, HR 60, RR 16, and oxygen saturation 97% on room air. His rhythm strip is seen below. Which is the most appropriate management for this rhythm?

A. Aspirin

B. Cardioversion

C. Observation

D. Temporary pacing

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

D. This ECG demonstrates type II second-degree heart block. Second-degree heart block is defined by one or more impulses not reaching the ventricles and is classified as type I and type II. Type II second-degree heart block, also known as Mobitz II, is caused by an infranodal conduction abnormality, most commonly in the bundle of His or the purkinje fibers. ECG findings demonstrate random dropped QRS complexes without any changes in the PR interval. Type II second-degree heart block carries a worse prognosis than type I second-degree heart block and necessitates treatment. Unlike type I, atropine has no effect on the His-Purkinje system and may worsen conduction. Temporary pacing is critical in this case because this rhythm can devolve to complete heart block. In the ED, transcutaneous or transvenous pacing should be instituted if the patient is symptomatic and there should be immediate consultation with a cardiologist. Patients with Mobitz II in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction should be treated with temporary pacing and revascularization; following revascularization most conduction abnormalities will improve or resolve and will not require permanent pacing.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

Question 4.

A man who presents with syncope is placed on the cardiac monitor. On the monitor you note a repeating trend of 6 P waves, 5 of which are followed by a narrow QRS complex and 1 of which is not followed by a QRS complex. The PR interval during this trend progressively increases. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. First-degree AV block

B. Third-degree AV block

C. Type I second-degree AV block

D. Type II second-degree AV block

[accordion]

[toggle title=”Answer” state=”closed”]

C. A key distinction between first-degree and second-degree heart block is that in first-degree block the P wave is always followed by a QRS complex. In other words, the ratio of P waves to QRS complexes is 1:1, or, the electrical signal from the atria always passes to the ventricles. In second-degree AV block, the electrical impulse sometimes gets to the ventricles. There are two main types of second-degree AV block. In Mobitz type I, or Wenckebach, second-degree block, there is a progressive beat-to-beat lengthening of the PR interval until a P wave does not conduct through the AV node. The absent conduction and resultant “missing” QRS complex is called a “dropped” QRS, which represents an absent beat of ventricular contraction. First-degree AV block (A) has a 1:1 ratio of P waves to QRS complexes. Mobitz type II second-degree heart block (D) is characterized by a nonconducted P wave which is not preceded by progressive PR interval prolongation. AV dissociation, or third-degree AV block (B), occurs when none of the P waves conduct through the AV node. This complete AV block occurs with separate atrial and ventricular rates. There is no discrete correlation or trend between P waves and QRS complexes.

[/toggle]

[/accordion]

References:

- Lang R, David D, Klein HO, et al. The use of the balloon-tipped floating catheter in temporary transvenous cardiac pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1981;4(5):491-6.

- Roberts J and Hedges J. “Emergency Cardiac Pacing.” Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine